Designed by Paul Smith 2006. This website is copyrighted by law.

Material contained herewith may not be used without the prior written permission of FAUNA Paraguay.

Photographs on this web-site are used with permission.

Didelphis albiventris Lund 1840 Image Gallery

TAX: Class Mammalia; Subclass Theria; Infraclass Metatheria; Order Didelphimorphia; Family Didelphidae; Subfamily Didelphinae, Tribe Didelphini (Myers et al 2006, Gardner 2007). The genus Didelphis was defined by Linnaeus, 1758. There are four known species according to the latest revision (Gardner 2007) two of which are present in Paraguay. The generic name Didelphis is from the Greek meaning "double womb", and albiventris is derived from the Latin for "white-bellied". The species is monotypic (Gardner 2007). Only recently is the name D.albiventris gaining widespread acceptance for this species, with the names D.azarae Temminck (1824) and D.paraguayensis JA Allen (1902) being frequently the most frequently used. The former name was rejected by Hershkovitz (1969) who pointed out that Temminck´s description is based on several "black-eared opossums" and not this species. The latter name comes from Oken (1816) and given that his names were deemed non-Linnean by the ICZN it is unavailable for usage. The next oldest available name for the species is D.albiventris Lund (1840). This species was "Le Micouré Premier" of de Azara (1801). Synonyms adapted from Gardner (2007):

[Didelphis] albiventris Lund 1839:233. Nomen nudum.

Didelphis albiventris Lund 1840:18. Type locality "Rio das Velhas", Lagoa Santa, Minais Gerais, Brazil.

Didelphis poecilotus JA Wagner 1842:358. Type locality "Angaba" (=Cuiabá), Matto Grosso, Brazil.

D[idelphys]. poecilonota Schinz 1844:504. Type locality "Angaha in Brazilien" (=Cuiabá), Matto Grosso, Brazil.

Didelphis azarae Tschudi 1845:143. In part, not D.azarae Temminck 1824.

Didelphis poecilotis JA Wagner 1847:126. Spelling emendation

Didelphis leucotis JA Wagner 1847:127. Based on "Le Micouré Premier" of de Azara (1801) with type locality "Paraguay".

Gamba aurita var. brasiliensis Liais 1872:329. In part. Implied type locality Brazil.

Didelphis marsupialis var. azarae O.Thomas 1888:129. Name combination. Not Didelphys azarae Temminck (1824).

Didelphis marsupialis azarae Cope 1889:129. Name combination. Not Didelphys azarae Temminck (1824).

Didelphys Azarae m[utación]. antiqua Ameghino1889:278. Type locality "Barrancas del Río Primero", Córdoba, Argentina.

Didelphys lecehi Ihering 1892:98. Type locality "Sul do Río Grande" Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

Didelphis marsupialis var. albiventris Winge 1893:7. Name combination.

[Didelphys (Didelphys) marsupialis] Azarae Trouessart 1898:1235. Name combination.

Did.[elphis] paraguayensis JA Allen 1902:251. Based on Didelphis paraguayensis of Oken (1916) in turn based on de Azara (1801) with type locality "Asunción, Paraguay"

[Didelphys (Didelphys)] paraguayensis Trouessart 1905:853. Name combination.

[Didelphis (Didelphis)] poecilotis Matschie 1916:268. Name combination.

[Didelphis (Didelphis)] albiventris Matschie 1916:268. Name combination.

[Didelphis (Didelphis)] lechei Matschie 1916:268. Name combination.

D.[idelphis] opossum Larrañaga 1923:346. Name combination. Not Didelphis opossum Linnaeus, 1758.

Didelphis paraguayensis bonariensis Marelli 1930:2. No type locality, but subsequently restricted to Provincias Buenos Aires and Santa Fé, Argentina by Marelli (1932).

Didelphis paraguayensis dennleri Marelli 1930:2. No type locality, but subsequently restricted to Provincia Buenos Aires, Argentina by Marelli (1932).

Didelphys azarai Ringuelet 1954:295. Incorrect spelling of, but not Didelphys azarae Temminck. 1824.

Didelphis lechii Vieira 1955:345. Incorrect spelling.

Didelphis azarae azarae Cabrera 1958:41. Name combination, not Didelphys azarae Temminck. 1824.

Didelphis albiventris Hershkovitz 1969:54. First modern use of current name.

ENG: White-eared Opossum (Gardner 2007), Azara´s Opossum (Eisenberg 1989), White-belly Opossum (Noguiera 1988), Cassaco (Gardner 2007).

ESP: Comadreja común (Esquivel 2001, Massoia et al 2000), Zarigüeya común de orejas blancas (Emmons 1999, Esquivel 2001), Comadreja overa (Massoia et al 2000, Parera 2002, Eisenberg 1989), Comadreja mora (Massoia et al 2000, Emmons 1999), Picaza (Massoia et al 2000), Carachupa oreja blanca (Cuéllar & Noss 2003), Comadreja negra (Marelli 1930), Comadreja picaza, Comadreja orejas blancas, Mbicuré común (Massoia et al 2006).

GUA: Ngure (Esquivel 2001), Mykure PMA (SEAM et al 2001, Villalba & Yanosky 2000), Guné Ac (Villalba & Yanosky 2000), Mbicuré (Parera 2002), Mbikuré eté (Massoia et al 2000), Karachupa (Cuéllar & Noss 2003).

DES: A robust marsupial, the largest in Paraguay. Males are larger than females with more prominent canines. Triangular head with pronounced, pointed snout and fairly large, rounded white ears. The nose is pink and the eyes are brown. Head mostly white with a black medial stripe and black patches around the eyes. Pelage dense and usually grey (88% of individuals) darker along the medial line, and often appearing somewhat unkempt due to the presence of different length hairs. A rare dark phase makes up about 12% of individuals. Unique amongst opossums is that Didelphis possess long, white-tipped guard hairs. Basally the pelage is often paler and greyer, though there is great variation amongst individuals and some are distinctly dark. Ventrally somewhat paler. The tail is furred basally and naked for the rest of its length save for a few scarce hairs. Naked area of the tail is black on the basal half and white on the distal half. Young animals are similar but have less obviously white ears. Albinism has been reported but is rare. Females possess a marsupium (pouch) in which the teats are contained, arranged in a circle with one in the middle. The number of teats is variable but commonly there are 13 (Eisenberg 1989). Sexual organs of both species are linked to the anal duct in their latter half and both exit via an external cloaca. The mostly naked tail is prehensile and the thumb is opposable, adaptations for an arboreal existence. CR - Occipitonasal length 84mm. Robust cranium with long, broad snout. Well-developed sagittal and lamboidal crest in adults. Interorbital ridge thin with a long postorbital constriction behind the postorbital process. Broad zygomatic arch only slightly expanded. Brain case small. (Díaz & Barquez 2002). Abdala et al (2001) described the postweaning ontogeny of the skull of this species and defined the following characteristics as useful for distinguishing between juvenile (<8 months old) and adult (>9.5 months old) skulls: Supraorbital border of frontal, postorbital constriction, secondary foramen ovale and groove for petrosal sinus are all present in the adult and absent in juvenile; Gyrus of anterior semicircular canal is narrow in juvenile and wide in adult; Cavum supracochlear floor is incomplete in juvenile and complete in adult; Petrosal, promontorium and tympanic process of the petrosal relatively large in juvenile and relativel small in adult; Fossa subarquata and internal acoustic meatus relatively large in juvenile and relativel small in adult; Dorsal margin of foramen magnum formed by interparietal in juveniles and exoccipitals in adults; Exoccipital and basioccipital partially fused in juveniles and completely fused in adults; Petrosal fixed to squamosal in juveniles, loosely attached in adults; Sphenorbital fissure and foramen rotundum almost adjacent in juvenile but separated by wall of alisphenoid in adults; Sphenorbital fissure and foramen ethmoidal almost adjacent in juvenile but separated by wall of orbitosphenoid in adults. Mares & Braun (2000) gave the following combined sex measurements for 6 adult specimens (2 male, 3 female, 1 unsexed) from Argentina: Greatest Length of Skull 86mm (75.3-94mm); Condylobasal Length 84.8mm (75.3-94mm); Interorbital Width 10.6mm (9.8-11.2mm); Zygomatic Width 45.1mm (39.2-53.6mm); Width of Braincase 25.2mm (23.1-27.4mm); Mandibular Length 68.9mm (60-76.6mm), Palate Length 50.2mm (45.7-55.1mm). DF: I5/4 C1/1 P 3/3 M 4/4 = 50. P1 small, P2 and P3 similar in size (Díaz & Barquez 2002). P3 not peg-like and narrow with a pronounced posterior-labial groove. (Lemos & Cerqueira 2002). Tyndale-Biscoe & MacKenzie (1976) summarised ageing in Didelphis opossums based on dental wear by defining 7 age classes as follows: Dental Class 1: (<4 months) dP3 M1 no cusp wear; Dental Class 2: (4-6 months) dP3 M2 no cusp wear; Dental Class 3: (5-7 months) dP3 M3 no cusp wear; Dental Class 4: (6-11 months) P3 M3 no cusp wear; Dental Class 5: (9-16 months) P3 M4 no cusp wear; Dental Class 6: (15-23 months) P3 M4, cusp wear on P3 and M1-2; Dental Class 7: (>22 months) P3 M4, cusp wear on P3 and M3-4. Astúa de Morães et al. (2001) describe supernumerary molars in two specimens of this species. Specimen DZUFMG 120 showed a small ovaloid molar, 33% the size of M4 erupted behind the right M4. Specimen MN 2250 has an extra molar behind every series. The upper left molar is smaller than the corresponding M4 and slightly rotated anti-clockwise. That on the upper right side is identical to the M4 but about half the size. The crowns of both upper extra molars lie below the occlusal series. The molars on the lower series are similar but not identical to the respective M4s. Mares & Braun (2000) gave the following combined sex measurements for 6 adult specimens (2 male, 3 female, 1 unsexed) from Argentina: Length of Upper Toothrow 32.9mm (29.7-36.1mm); Length of Lower Toothrow 36.4mm (32.2-40.8mm). CN: 2n=22. Karyotype with 10 uni-armed autosomes with terminal centromeres, an acrocentric X and a minute Y.

TRA: Didelphis prints are characteristically wider than they are long with a notably uneven appearance, especially on the hindfoot which shows fore toes displaced to one side and the opposable thumb on the other side. The tail being dragged behind the body often leaves an impression. FP: 4.3 x 5cm; HP: 3.2 x 6cm; PA: 12cm. (Villalba & Yanosky 2000, Massoia et al 2009).

MMT: A large and robust Didelphid with tail approximately the same length as the head and body. TL: 76.3cm (59-89.2cm); HB: 30-44.2cm; TA: 37.3cm (29-45cm); FT: 5.96cm (4.2-6.8cm); EA: 5.4cm (4.1-6.5cm); WT: 1560g (500-2500g); WN: 0.15g (Massoia et al 2001, Parera 2002, Emmons 1999, SEAM et al 2001, Redford & Eisenberg 1992). Mares & Braun (2000) gave the following combined sex measurements for 27 adult specimens (14 male, 12 female, 1 unsexed) from Argentina: TL: 67.4cm (38-80.7cm); HB: 34.46cm (26-42.5cm); TA: 32.94cm (12-39.5cm); FT: 5.29cm (4.8-6.1cm); EA: 5.42cm (5-6cm); WT: 1173.8g (508-2000g).

Cáceres & Monteiro-Filho (1999) noticed a correlation between head length and age class, and stated that the measurement may be used to estimate body length. Mass was noted to increase during autumn in preparation for the winter season with fewer resources, and older adults showed tendencies towards obesity. Adult size is reached about 10 months. They gave the following external body measurements for differing age classes of males and females from southern Brazil:

Infant (4-6 months old, dental class 2): Head: male 7.4cm (+/-0.6) female 7.1cm (+/-0.6); WT: male 222g (+/-84) female 200g (+/-88).

Young (5-7 months old, dental class 3): Head: male 9.8cm (+/-0.7) female 9.7cm (+/-0.5); Body: male 23.5cm (+/-1.7) female 25.2cm (+/-1.9); FT: male 4.7cm (+/-0.3) female 4.8cm (+/-0.6); WT: male 623g (+/-210) female 809g (+/-154).

Subadult (6-11 months old, dental class 4): Head: male 11.2cm female 11.2cm (+/-1.1); Body: male 30.9cm female 28.9cm (+/-0.4); FT: male 5.1cm female 5.6cm (+/-0.3); WT: male 1180g female 1042g (+/-194).

Young adult (9-16 months old, dental class 5): Head: male 13.3cm (+/-0.7) female 12cm (+/-0.2); Body: male 35.2cm (+/-0.6) female 33.9cm (+/-1.9); FT: male 5.8cm (+/-0.3) female 5.6cm (+/-0.4); WT: male 1673g (+/-54) female 1377g (+/-202).

Adult (15-23 months old, dental class 6): Head: female 13.8cm (+/-0.7); Body: female 38cm (+/-2.6); FT: female 6.1cm (+/-0.4); WT: female 1786g (+/-182).

Senile adult (>22 months old, dental class 7): Head: female 14.1cm (+/-1); Body: female 38.1cm (+/-0.2); FT: female 6.1cm (+/-0.1); WT: female 2020g (+/-78).

SSP: This is generally the most commonly encountered and widespread Paraguayan marsupial. It is most likely to be confused with the Didelphis aurita, which is smaller, much blacker in overall colouration and more strictly associated with humid forest habitat - ie. they are much less tolerant of human presence. As suggested by the common name this species can most easily be identified by its white as opposed to black ears. The fur at the base of the tail extends further down the tail in this species than in the Black-eared Opossums. White ear colour is much less pronounced in juveniles and so care must be taken in their identification. (Redford & Eisenberg 1992).

DIS: Widely distributed east of the Andes from Colombia and western Venezuela south to Provincia Rio Negro (41ºS) in Argentina, north to the Atlantic coast of Brazil, though absent from the Amazon Basin where it is replaced by other species. In Argentina the species occurs west as far as Barreal (31°36’ S, 69°27’ W) in Provincia San Juan at an altitude of 1900m (Teta & de Tomasso 2009). In Paraguay the species is widely distributed throughout eastern Paraguay where it even occurs in the suburbs of Asunción, and also through the Humid Chaco and Pantanal region, being absent only from the Dry Chaco ecotone. (Parera 2002, SEAM et al 2001).

HAB: An adaptable habitat generalist able to tolerate a large degree of habitat disturbance and actively seeking human habitation and exploiting them for food resources in rural areas. White-eared Opossums occur in humid forest and edge (ECOSARA Biodiversity Database) being most common where degraded or affected by human activity, but are equally at home in cerrado and relatively open grassland areas provided that sufficient food and sleeping places are available. They tend to prefer areas in close proximity to water and trees and are apparently absent from the driest areas of the Chaco (Parera 2002, SEAM 2001), though they are present and common in the Chaco and Chiquitania of Bolivia (Cuéllar & Noss 2003.

ALI: Omnivorous and opportunistic, able to exploit a wide range of food sources from plant matter including fruit, leaves and seeds, to animal matter such as invertebrates, small mammals and birds. When a particular foodstuff is abundant it is typically exploited repeatedly until it is exhausted. In Misiones, Argentina stomachs contained worms, ants, small birds, eggshell and plant matter (Redford & Eisenberg 1992). Cáceres (2002) investigated diet and the species role as seed dispersers through fecal analysis in Curitiba, Brazil. He found the species to be strongly omnivorous and that diet did not vary with age. Invertebrates occurred in 100% of scats, fruits in 76%, vertebrates in 58% and refuse 8%. Fruit consumption and the consumption of some animal prey (eg reptiles and coleoptera) increased during the wet season, whilst other fruits and different animal prey (eg birds and diplopods) were more prominent during the drier part of the year. Animal prey consisted largely of species occurring in leaf litter, suggesting predominately terrestrial foraging. The following items were recorded in scats, with percentages representing the percentage of scats which contained the given item: Vertebrates (58%) - Birds 28%, Reptiles 19% (wet season only and mainly Liotyphlops beui), Mammals 15% and Fish 1%. Invertebrates (100%) - Coleoptera 76%, Opiliones 60%, Blattaria 44%, Diplopoda 41%, Pulmonata 41%, Hymenoptera (mainly ants) 31%, Isopoda 13%, Lepidoptera (larvae) 10%, Decapoda 8%, Orthoptera 4% and Hemiptera 1%. Fruits taken were mainly coloniser species emphasising the role of the species as important dispersers and included the following families - Solanaceae (Solanum sanctaecatharinae 18%, S. cf maioranthum 9%, Vassobia breviflora 7%, Solanum sp 4%, Cyphomandra corymbiflora 1%), Passifloraceae (Passiflora actinia 18%, Passiflora sp 1%), Moraceae (Morus nigra 11%), Rosaceae (Rubus erythrocladus 11%, Rubus rosifolius 4%), Piperaceae (Piper gaudichaudianum 6%), Cucubitaceae (Melothria cucumis 7%, Cucumis sp 6%), Arecaceae (Syagrus romanzoffiana 3%), Poaceae 3%, Myrtaceae (Psidium guajava 1%), Rutaceae (Citrus sp. 1%), Melastomataceae (Leandra australis 1%) and Erythroxylaceae (Erythroxylum deciduum 1%). All seeds that passed through the digestive system of the animal undamaged were less than 0.8cm long in adults and less than 0.4cm long in juveniles. Larger seeds were either destroyed, or in the case of very large seeds (eg Syagrus romanzoffiana) discarded without being consumed. Cáceres & Monteiro-Filho (2007) examined germination rates of seeds consumed by Didelphis opposums in southern Brazil, finding that germination rates of seeds that had passed through opossum guts were similar to those of control groups for thirteen species of pioneer plants, with the exception of Rubus rosifolius which required gut passage for germination. Alessio et al (2005) documented feeding on tree gum by this species in the northeastern Atlantic Forest of Brazil, with opossums taking advantage of "jellified gum balls" in holes on the trunk of a Tapirira guianensis tree (Anacardiaceae), a resource also exploited by the gum-feeding primate the Tufted Marmosets Callithrix jacchus. In areas close to human habitation they take advantage of agriculture, orchards and even refuse. (Massoia et al 2000, Smith 2007). At Estancia Nueva Gambach, San Rafael National Park, they have been seen feeding on mandarin fruits (Citrus sp.), fruits of the Pindó Palm (Syagrus romanzoffiana) and frequently raid the area around the house in search of chicken and quail eggs from the coup, occasionally killing adult birds without consuming them (Hans Hostettler pers. comm., Smith 2007) - the Spanish name Comadreja overa refers to their fondness for birds eggs. Gazarini et al (2008) reported that an individual in Maringá, southern Brazil predated bats caught in bat nets, including at least one example of Artibeus lituratus and likely also Sturnira lilium. Oliveira & Santori (1999) note that the species is immune to the effects of snake venom and studied the technique used in the predation of Bothrops jararaca under captive conditions. Juveniles and adults dispatched snakes in the same way. On initial approach the opossum sniffed at the snake, before moving towards the head end and seizing it violently at the back of the head. The snake was then tossed and shook using the mouth and feet for a mean of 9s (+/-4s) using the mouth and forefeet until it was subdued. The snake was occasionally released before it was ingested. The snake was then consumed head first while sitting in an erect posture on the hind feet with a mean time for total ingestion of 24 mins 24s (+/-8mins 12s). The snake was held with one forefoot and chewed with the teeth of the same side, whilst the other forefoot was used for additional support in the sitting position. The foot used to hold the snake was changed occasionally with a mean time using the right foot of 8 mins 30s (+/-8mins 56s) and mean time using the left foot of 10 mins 37s (+/-3mins 22s). Similar techniques are used to kill mice and chickens under laboratory observations suggesting that it is not a specialist adaptation to snake predation. Astúa de Morães et al. (2003) experimentally tested the proportions of protein, lipid, carbohydrate and fibre in the diet of adults (n=6) and juveniles (n=7) of this species under laboratory condtions. Mean proportions per 100g dry weight of food were: protein ad. 20.89g (+/-8.53), juv. 5.58g (+/-2.44); lipid ad. 1.66g (+/-1.49), juv. 1.53g (+/-1.41); carbohydrate ad. 27.90g (+/-7.71), juv. 4.69g (+/-4.92); fibre ad. 1.68% (+/-0.39), juv. 1.19% (+/-0.36). Santori et al (2004) described and illustrated the gut morphology of this species and associated it with dietary habits.

REP: The stimulus for breeding in Didelphis is the amount of daylight and acts primarily on the sexual cycle of the female. (Rademaker & Cerquiera 2006). Breeding activity takes place from August to February in Misiones, Argentina (Massoia et al 2006). Two reproductive cycles have been reported during the course of the year in the Argentinian Chaco and in temperate Buenos Aires (Regidor & Gorostiague 1996) but in the Brazilian caatinga only one period of oestrus is recorded annually, timed to coincide with the rains. Peaks of reproduction in Provincia Buenos Aires are at the beginning of September and in late November or December with the first breeding period accounting for about 70% of the total young produced and only females that conceived early in the first breeding period being able to reproduce a second time (Regidor & Gorostiague 1996). Astúa de Morães & Geise (2006) captured a pregnant female that was young enough to have been born and reproduce in the same reproductive season. A female in Colombia which had its pouched young removed was in oestrus again when captured 14 days later. However females maintained in captivity after removal of their young did not return to oestrus and maintenance in captivity may impede the normal oestral cycle. (Tyndale-Briscoe & MacKenzie 1976). Regardless of the limited period of female fertility, males seem to be in a constant search for copulation, being violently rejected by non-receptive females for much of the year. However Nogueira (1988) challenged that view and suggested that males show subtle differences in their genital systems throughout the year and can reproduce opportunistically. Receptive females cede to a brief copulation before chasing the male away and returning to a solitary existence. The gestation period is short, lasting 12-14 days (Tyndale-Bisoce & MacKenzie 1976). Females give birth to 4-13 young in a still embryonic state and less than 15mm in length, these immediately making their way to the pouch and attaching themselves to a teat (Esquivel 2001, Parera 2002, Redford & Eisenberg 1992). Sex ratio has been measured at 1.11 males to females for pouched young in Buenos Aires (Regidor & Gorostiague 1996). The number of young may exceed the number of available teats and those that are unable to feed quickly die. Rademaker & Cerquiera (2006) demonstrated that latitude has a positive effect on litter size and the duration of the breeding season (which decreases with latitude) is negatively related to litter size. Average litter sizes of 6.2 (Brazilian caatinga), 4.2 (Colombia), 7.1 (Argentina) and 9.4 (Uruguay) have been reported (Parera 2002, Redford & Eisenberg 1992). Regidor & Gorostiague (1996) gave a range of 4 to 9 young for 41 females captured in Provincia Buenos Aires. Eisenberg (1989) states that older females produce smaller litters, but Regidor & Gorostiague (1996) found no evidence to support that claim and no correlation between body weight of the mother and litter size. During their second month the juveniles leave the pouch and cling to the back of the female, returning only to suckle and are weaned at 3 to 4 months. The testicles of young males descend at the time of weaning (Eisenberg & Redford 1999). Sexual maturity is reached at 7.5 months according to Regidor & Gorostiague (1990) but Astúa de Morães & Geise (2006) captured a female with 6 pouched young in Age class 2 (4.5-7 months old), this being younger than all previously documented reproductive females in this species but within the known range for Didelphis aurita. For a detailled account of spermatogenesis in this species see Quieroz & Noguiera (2006).

BEH: Activity Levels Though captive individuals have exhibited remarkable social behaviours, wild White-eared Opossums are solitary animals and generally nocturnal in behaviour. Locomotion Cunha & Vieira (2002) note that Didelphis opossums move on thin limbs even when broader and apparently more stable limbs are available, distributing their weight across all four limbs and using the prehensile tail as a fifth limb. All levels of the forest strata are utilised and they are also capable of swimming short distances and frequently do so to cross streams. (Massoia et al 2000). Home Range Though they are not strictly territorial and even slightly nomadic in behaviour, adults will defend the area occupied at any given time (Novak 1991) and there is apparently a greater tendency towards territoriality in areas of sympatry with Black-eared Opossums (Parera 2002). Home ranges in Argentina avergaed 0.57ha (Eisenberg 1989). Nest holes are changed with regularity. Roosts Adults spend the day in a hollow trunk or other suitable nest hole lined with grass, fur and feathers and emerge at sunset to begin the daily routine. Roost sites are defended ferociously. They sniff the air on emergence and if disturbed can remains motionless for several minutes with the ears directed towards the source of the disturbance. (Massoia et al 2006). Defensive Behaviour White-eared Opossums prefer to flee to trees or holes in trunks when they feel threatened. An individual at Pro Cosara hid itself within a bunch of fruits and palm fronds in a Pindó Palm on the approach of an observer and watched quietly (Smith 2007). Though capable of running fairly rapidly on level ground they are agile but somewhat slow movers in the branches of trees and when approached closely threaten with the mouth open (Smith 2007), sometimes also producing a disagreeable smelling glandular secretion from the cloaca (Massoia et al 2006). On rare occasions captured individuals may briefly "play possum", lying prone with the mouth open as though dead (Massoia et al 2000, Parera 2002, Smith 2007), but this is less common than in the North American Virginia Opossum Didelphis virginiana. If held by the tail with the front feet on the ground they attempt to escape by walking, apparently oblivious to the hand holding their tail. However if the animal is lifted from the ground they immediately attempt to bite, using the powerful prehensile tail to curl the body upwards (Smith 2007). Enemies This species is frequently preyed upon by felines, foxes, raptors (including Rupornis magnirostris and Tyto alba) and large snakes such as Eunectes notaeus and Boa constrictor (Parera 2002). In a roadkill study in Santa Catarina, Brazil this species was found to be the second most common victim of traffic consisting of 17.1% of the 256 individuals of 20 species sampled (Cherem et al 2007). In other similar studies in Brazil, on the B2-277 bordering PN Iguacu in Paraná State, Brazil D. aurita and D. albiventris represented 16.2% of the mamals hit by cars (Lima & Obara 2004), whilst this species represented 48.9% of all the roadkill on the RS-040 (Rosa & Mauhs 2004) and 28.8% of roadkill on six rodavias in São Paulo State (Prada 2004). Individuals killed by electrocution from power lines have been documented in Argentina (Massoia et al 2006). Parasites Limardi (2006) notes the following ectoparasites of this species in Brazil: Siphanoptera Craneopsylla minerva (Stephanocircidae); Adoratopsylla ronnai (Ctenophthalmidae); Ctenocephalides felis (Pulicidae); Polygenis tripus, P.rimatus and Rhopalosyllus lutzi, (Rhopalopsyllidae). Acari: Metastigmata Ixodes loricatus, I.amarali, Amblyomma sp., A.cajennense, Ornithodoros talaje (Ixodidae). Acari: Mesostigmata Ornithonyssus wernecki (Macronyssidae); Androlaelaps fahrenholzi, Gigantolaelaps butantanensis, G.vitzthumi and Laelaps mastacalis(Laelapidae). Acari: Prostigmata Archemyobia latipilis and Archemyobia sp. (Myobiidae). Acari: Astigmata Didelphilichus serrifer (Atopomelidae). Thatcher (2006) lists the following endoparasites of this species in Brazil: Protozoa Trypanosoma cruzi, Babesia ernestoi. Longevity Regidor & Gorostiague (1996) stated that few individuals in Buenos Aires survive more than 20 months in the wild and only survive long enough to participate in one reproductive season.

HUM: This common marsupial comfortably tolerates the close proximity of humans and in some areas may even actively seek human dwellings for access to food resources. It is likely that human activity has enabled them to considerably extend their range, with deforestation creating optimal habitat (Parera 2002). The species is frequently seen dead on roads. It is used as an example of good parenting for educational purposes on account of the way the young are maintained close to the mother by being raised in a pouch (SEAM et al 2001). Considered a pest species in some areas as they regularly break into to chicken coups to steal eggs and birds (Hans Hostettler pers. comm.) and in Argentina they are actively persecuted for that reason (Massoia et al 2006). They are attracted to fruiting trees in orchards and gardens where they likely have a low impact on yield (Smith 2007). Though the species is appreciated for its white meat in the area of Santiago del Estero in Argentina (Parera 2002) it has not been registered in the diet of indigenous tribes in Paraguay (Cartés 2007). In certain areas in Argentina the meat is considered to have curative properties, whilst a skin kept under the bed or a stew made with the tail are both believed to assist in a smooth birth (Massoia et al 2000). In Argentina the fat of the species has been used as a supposed cure for haemorrhoids and skins are used to make coats, though the practice has not been recorded in Provincia Misiones (Massoia et al 2009). A high incidence of infection with Trypanosoma cruzi, the parasite responsible for Chaga´s disease, was recorded in Santiago del Estero, Argentina (Parera 2002). Snake venom inhibition is exhibited by the serum of this species which has made it an important laboratory animal (Hingst et al 1998).

CON: Globally considered to be of Low Risk Least Concern by the IUCN, click here to see their latest assessment of the species. The Centro de Datos de Conservación in Paraguay consider the species to be secure and under no threat in Paraguay, giving it the lowest risk code N5. The species is not listed by CITES. This species is widespread, adaptable and frequently common. Densities of 0.4-4.4 per hectare have been recorded in the Caatinga of Brazil and 2.5 per hectare in Tucuman Argentina. In Paraguay three separate individuals were killed raiding the same chicken coup in Alto Verá, Departamento Itapúa during the course of December 2006 (Hans Hostettler pers. comm.). A study in Tucumán, Argentina found the average home range to be 5,700m2 for six animals (Redford & Eisenberg 1992).

Citable Reference: Smith P (2007) FAUNA Paraguay Online Handbook of Paraguayan Fauna Mammal Species Account 1 Didelphis albiventris.

Last Updated: 1 July 2009.

References:

Abdala F, Flores DA, Giannini NP 2001 - Postweaning Ontogeny of the Skull of Didelphis albiventris - Journal of Mammalogy 82: p190-200.

Alessio FM, Pontes ARM, da Silva VL 2005 - Feeding by Didelphis albiventris on Tree Gum in the Northeastern Atlantic Forest of Brazil - Mastozoologia Neotropical 12: p53-56.

Allen JA 1902 - A Preliminary Study of the South American Opossums of the Genus Didelphis - Bulletin AMNH 16: p249-279.

Ameghino F 1889 - Sinopsis Geológico-Paleontológica de la Argentina in Segundo Censo Nacional de la República Argentina - La Plata, Supplemento.

Astúa de Morães D, Geise L 2006 - Early Reproductive Onset in the White-eared Opossum Didelphis albiventris, Lund 1840 (Didelphimorphia: Didelphidae) - Mammalian Biology 71: p299-303.

Astúa de Morães D, Lemos B, Finotti R, Cerquiera R 2001 - Supernumerary Molars in Neotropical Opossums (Didelphimorphia, Didelphidae) - Mammalian Biology 66: p193-203.

Astúa de Morães D, Santori RT, Finotti R, Cerquiera R 2003 - Nutritional and Fibre Contents of Laboratory-established Diets of Neotropical Opossums (Didelphidae) p225-233 in Jones M, Dickman C, Archer M Predators with Pouches: The Biology of Carnivorous Marsupials - CSIRO Publishing, Australia.

Azara F de 1801 - Essais sur l´Histoire Naturelle des Quadrupèdes de la Province du Paraguay - Charles Pougens, Paris.

Cabrera A 1958 - Catálogo de los Mamíferos de América del Sur - Revista Museo Aregntino de Ciencias Naturales Bernadino Rivadavia Zoology 4: p1-307.

Cáceres NC 2002 - Food Habits and Seed Dispersal by the White-eared Opossum Didelphis albiventris in Southern Brazil - Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment 37: p97-104.

Cáceres NC, Monteiro Filho EL de A 1999 - Tamanho Corporal em Populacões Naturais de Didelphis (Mammalia: Marsupialia) do Sul do Brasil - Revista Brasileira de Biologia 57: p461-469.

Cáceres NC, Monteiro-Filho EL de A 2007 - Germination in Seed Species Ingested by Opossums: Implications for Seed Dispersal and Forest Conservation - Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology 50: p921-928.

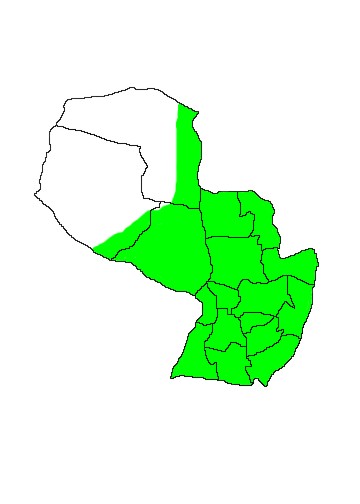

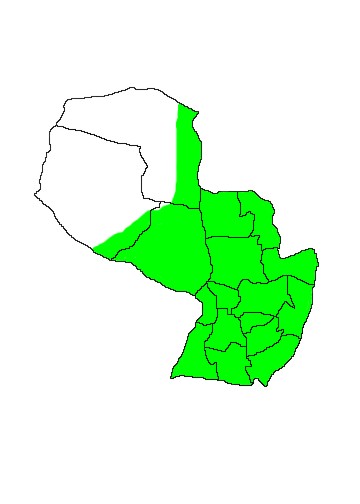

MAP 1:

Didelphis albiventris

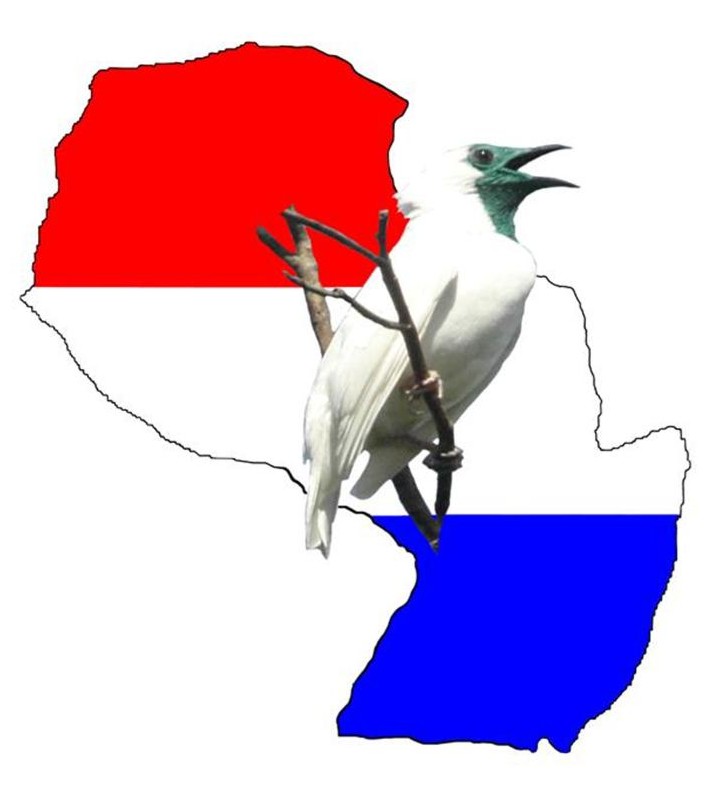

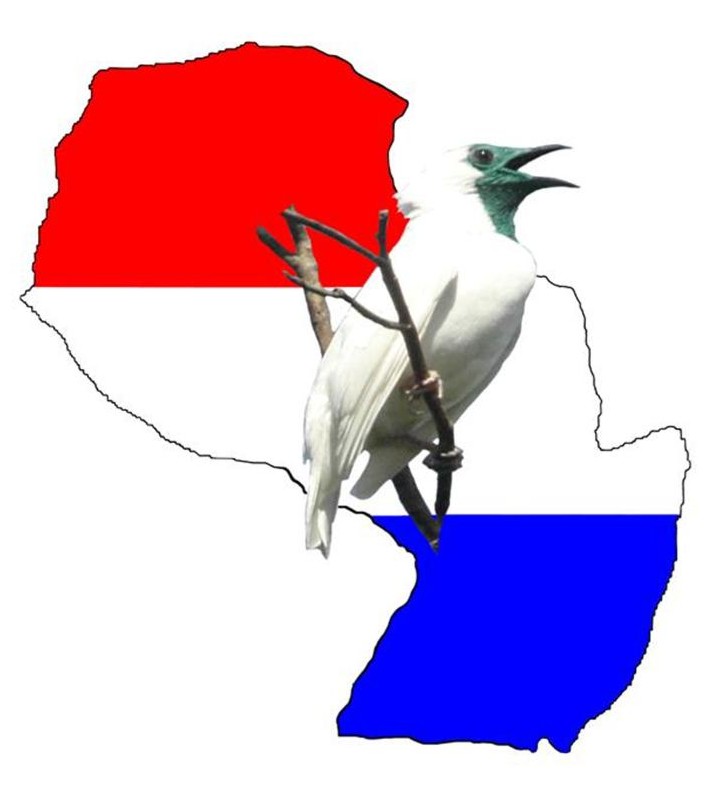

PRINT 1:

Didelphis albiventris

Adapted from Massoia et al (2006) and Yanosky & Villalba (2000).

Click the image to enlarge it.

Cartés JL 2007 - Patrones de Uso de los Mamíferos del Paraguay: Importancia Sociocultural y Económica p167-186 in Biodiversidad del Paraguay: Una Aproximación a sus Realidades - Fundación Moises Bertoni, Asunción.

Cherem JJ, Kammers M, Ghizoni IR, Martins A 2007 - Mamíferos de Médio e Grande Porte Atropelados em Rodavias do Estado de Santa Catarina, Sul do Brasil - Revista Biotemas 20: p81-96.

Cimardi AV 1996 - Mamíferos de Santa Catarina - FATMA, Florianópolis.

Cope ED 1889 - On the Mammalia Obtained by the Naturalist Exploring Expedition to Southern Brazil - American Naturalist 23: p128-150.

Cunha AA, Vieira MV 2002 - Support Diameter, Incline and Vertical Movements of Four Didelphid Marsupials in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil - Journal of Zoological Society of London 258: p419-426.

Cuéllar E, Noss A 2003 - Mamíferos del Chaco y de la Chiquitania de Santa Cruz, Bolivia - Editorial FAN, Santa Cruz.

Díaz MM, Barquez RM 2002 - Los Mamíferos del Jujuy, Argentina - LOLA, Buenos Aires.

ECOSARA Biodiversity Database

Eisenberg JF 1989 - Mammals of the Neotropics: Volume 1 The Northern Neotropics - University of Chicago Press, Chicago. Eisenberg JF, Redford KH 1999 - Mammals of the Neotropics: Volume 2 The Central Neotropics - University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Emmons LH 1999 - Mamíferos de los Bosques Húmedos de América Tropical - Editorial FAN, Santa Cruz.

Esquivel E 2001 - Mamíferos de la Reserva Natural del Bosque Mbaracayú, Paraguay - Fundación Moises Bertoni, Asunción.

Gardner AL 2007 - Mammals of South America Volume 1: Marsupials, Xenarthrans, Shrews and Bats - University of Chicago Press.

Gazarini J, Brito JEC, Bernardi IP 2008 - Predações Oportunísticas de Morcegos por Didelphis albiventris no Sul do Brasil - Chiroptera Neotropical 14: p408-411.

Hershkovitz P 1969 - The Evolution of Mammals on Southern Continents VI: A Zoogeographical and Ecological Review - Quarterly Review of Biology 44: p1-70.

Hingst E, D´Andrea PS, Santori R, Cerqueira R 1998 - Breeding of Philander frenata (Didelphimorphia, Didelphidae) in Captivity - Laboratory Animals 32: p434-438.

Ihering H von 1892 - Os Mamíferos do Rio Grande do Sul - Annuario do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul para o Anno 1893 de Graciano A de Azambuja p96-123.

Larrañaga DA 1923 - Escritos - Instituto Histórico y Geográfico del Uruguay, Montevideo.

Lemos B, Cerqueira R 2002 - Morphological Differentiation in the White-eared Opossum Group (Didelphidae Didelphis) - Journal of Mammalogy 83: p354-369.

Liais E 1872 - Climats, Géologie, Faune et Géographie Botanique du Brésil - Garnier Frères, Paris.

Lima SF, Obara AT 2004 - Levantamento de Animais Silvestres Atropelados na BR-277 às Margens do Parque Nacional do Iguaçu - Subsídios ao Programa Multidisciplinar de Proteção à Fauna - Accessed Online January 2009.

Limardi PM 2006 - Os Ectoparasitos de Marsupiais Brasileiros p27-52 in Cáceres NC, Monteiro-Filho ELA Os Marsupiais do Brasil:Biologia, Ecologia e Evolução - Editora UFMS, Campo Grande.

Linnaeus C 1758 - Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Clases, Ordines, Genera et Species Redacta Tabulisque Aeneis Illustrata. Editio Sexto. - G.Kiesenetteri, Stockholmiae.

Lund PW 1839 - Coup d´Oeil sur les Espèces Éteintes de Mammifères du Brésil, Estrait de Quelques Mémoires Présentés à l´Académie Royale des Sciences de Copenhague - Annals Sci. Nat. Zool. Paris series 2 11: 214-234

Lund PW 1840 - Fortsaettelse af Pattedyrene - K. Danske Vidensk. Selskab. Naturv. Math. Afhandl. 3: p1-56.

Marelli CA 1930 - Importancia de la Piel de la Comadreja Negra en la Industria Peletera - La Epoca 1930: p2.

Marelli CA 1932 - Los Vertebrados Exhibidos en los Zoológicos del Plata - Mem. Jardín Zool. La Plata 4: p1-275.

Mares MA, Braun JK 2000 - Systematics and Natural History of Marsupials from Argentina p23-45 in Reflections of a Naturalist: Papers Honoring Professor Eugene D Fleharty, Fort Hays Studies Special Issue 1.

Massoia E, Chebez JC, Bosso A 2006 - Los Mamíferos Silvestres de la Provincia de Misiones, Argentina - DVD-ROM.

Massoia E, Forasiepi A, Teta P 2000 - Los Marsupiales de la Argentina - LOLA, Buenos Aires.

Matschie P 1916 - Bemerkungen über die Gattung Didelphis L. - Sitzungsber. Gesells. Naturf. Freunde Berlin 1916: p259-272.

Myers P, Espinosa R, Parr CS, Jones T, Hammond GS, Dewey A 2006 - The Animal Diversity Web (online). Accessed December 2007.

Nogueira JC 1988 - Anatomical Aspects and Biometry of the Male Genital System of the White-belly Opossum Didelphis albiventris Lund 1841 During the Annual Reproductive Cycle - Mammalia 52: p233-242.

Novak RM 1991 - Walker´s Mammals of the World 5th Ed Volume 1 - Johns Hopkins, Baltimore.

Oken L 1816 - Lehrbuch der Naturgeschichte - Dritter Theil. Zoologie, August Schmid und Comp.

Oliveira ME, Santori RT 1999 - Predatory Behavior of the Opossum Didelphis albiventris on the Pitviper Bothrops jararaca - Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment 34: p72-75.

Parera A 2002 - Los Mamíferos de la Argentina y la Región Austral de Sudamérica - Editorial El Ateneo, Buenos Aires.

Prada CS 2004. Atropelamento de Vertebrados Silvestres em uma Região Fragmentada do Nordeste do Estado de São Paulo: Quantificação do Impacto e Análise dos Fatores Envueltos - Tese de Doutorado, Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Brasil, 129pp.

Queiroz GF de, Nogueira JC 2006 - Espermatogênese no Gambá Didelphis albibentris in Cáceres NC, Monteiro Filho ELA eds Os Marsupiais do Brasil: Biologia, Ecologia e Evolução - Editora UFMS, Campo Grande.

Rademaker V, Cerqueira R 2006 - Variation in the Latitudinal Reproductive Patterns of the Genus Didelphis (Didelphimorphia: Didelphidae) - Austral Ecology 31: p337-342.

Redford KH, Eisenberg JF 1992 - Mammals of the Neotropics: Volume 2 The Southern Cone - University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Regidor HA, Gorostiague M 1990 - Age Determination in the White-eared Opossum Didelphis albiventris - Vida Silvestre Neotropical 2: p75-76.

Regidor HA, Gorostiague M 1996 - Reproduction in the White-eared Opossum Didelphis albiventris Under Temperate Conditions in Argentina - Studies in Neotropical Fauna and Environment 31: p133-136.

Ringuelet AB de 1954 - Revision de los Didelfidos Fosiles de Argentina - Revista Museo de la Plata 3: p265-308.

Rosa AO, Mauhs J 2004 - Atropelamento de Animais Silvestres na Rodovia RS - 040 - Caderno de Pesquisa, Série Biologia 16: p35-42.

Santori RT, Astúa de Moraes D, Cerqueira R 2004 - Comparative Gross Morphology of the Digestive Tract in Ten Didelphidae Marsupial Species - Mammalia 69: p27-36.

Schinz HR 1844 - Systematisches Verzeichniss aller bis jetzt Bekannten Säugthiere oder Synopsis Mammalium nach dem Cuvier´schen System 1 - Jent und Gassmann, Solothurn.

SEAM, Guyra Paraguay, PRODECHACO 2001 - Especies Silvestres del Paraguay: Guía de Identificación de Especies con Importancia Económica - PRODECHACO, Asunción.

Smith P 2007 - Defensive Behaviour of a Captured White-eared Opossum Didelphis albiventris: A Short Note - Bellbird 2

Temminck CJ 1824 - Deuxième Monographie sur le Genre Sarigue - Didelphis (Linn.) in Monographies de Mammalogie ou Description de Quelques Genres de Mammifères dont les espèces ont été Observeés dans les Différens Musées de l´Europe - G.Dufour et E d´Ocogne, Paris.

Teta P, de Tommaso DC 2009 - Un Registro Marginal para la Comadreja Overa Didelphis albiventris (Didelphimorphia, Didelphidae) en la Provincia de San Juan, Argentina - Notulas Faunisticas 2a Serie 27.

Thatcher VE 2006 - Os Endoparasitos dos Marsupiais Brasileiros p53-68 in Cáceres NC, Monteiro-Filho ELA Os Marsupiais do Brasil:Biologia, Ecologia e Evolução - Editora UFMS, Campo Grande.

Thomas O 1888 - Catalogue of the Marsupialia and Monotremata in the Collection of the British Museum of Natural History - British Museum of Natural History, London.

Trouessart EL 1898 - Catalogus Mammalium tam Viventium quam Fossilium. Fasciculus V: Sirenia, Cetacea, Edentata, Marsupialia, Allotheria, Monotremata - R.Friedländer & Sohn, Berolini.

Tschudi J von 1845 - Untersuchungen Über die Fauna Peruana - Therologie 3-5: p77-244.

Tyndale-Biscoe CH, MacKenzie RB 1976 - Reproduction in Didelphis marsupialis and D.albiventris in Colombia - Journal of Mammalogy 57: p249-265.

Vieira CO da C 1955 - Lista Remissiva dos Mamíferos do Brasil - Arquivos Zool. Estado São Paulo 8: p341-474.

Villalba R, Yanosky A 2000 - Guía de Huellas y Señales: Fauna Paraguaya - Fundación Moises Bertoni, Asunción.

Wagner JA 1842 - Diagnosen Neuer Arten Brasilischer Säugthiere - Arch. Naturgesch. 8: p356-362.

Wagner JA 1847 - Beiträge zue Kenntniss der Säugthiere Amerika´s - Abhandl. Math.-Physik. König. Bayer. Akad. Wiss. München 5: p121-208.

Winge H 1893 - Jordfunde og Nulevande Pungdyr (Marsupialia) fra Lagoa Santa, Minas Geraes, Brasiliens - E Museo Lundii, Kjöbenhavn 2: p1-133.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special thanks to Juan Carlos Chebez for providing important literature and Nilton Cáceres for very kindly reviewing texts and providing a copy of his book Os Marsupiais do Brasil.