Designed by Paul Smith 2006. This website is copyrighted by law.

Material contained herewith may not be used without the prior written permission of FAUNA Paraguay.

Photographs on this web-site are used with permission.

REP: Polygynous with males dispersing in order to maximise their mating opportunities with the largely resident females. Presence of wounds on males during periods of high density suggests they react agonistically to each other when in search of a mate. (Mendel et al 2008). The stimulus for breeding in Didelphis is the amount of daylight and acts primarily on the sexual cycle of the female. (Rademaker & Cerquiera 2006). Females in Curtibia, Brazil had pouched young in August (Cáceres 2003) and a female in Misiones, Argentina had 12 pouched young (CRL=45mm) in November (Mares & Braun 2000). Gentile et al (2000) found breeding to begin in either July or August in Sumidouro, a rural area in Rio de Janeiro State and that from August to January almost all females were engaged in reproductive activity. Last weaning occurred in March. Kajin et al (2008) found reproduction to be seasonal in PN Serra dos Orgãos, Brazil, with breeding beginning in July (mid- dry season) and most females with pouched young in August. By February (end of the wet season) the breeding period was over but females were still lactating. Loretto & Vieira (2005) noted two breeding attempts in any one year in the same region, with the first matings taking place in June and second matings in November. Reproductive success is linked to rainfall and resource availability. Females began breeding at approximately 170 days old. Mean litter size was 7.33, with a range of 6-10 (n=16). Fecundity was greater in adults than subadults, but increased reproduction was found to reduce survival rate. Generation time was between 231.4 to 469 days. Rademaker & Cerquiera (2006) demonstrated that latitude has a positive effect on litter size and the duration of the breeding season (which decreases with latitude) is negatively related to litter size. Gentile et al (2000) found sex ratio of litters to be 1:1, with the greatest mortality of pouched young being at the beginning of lactation.

BEH: Activity Levels Predominately nocturnal, terrestrial and scansorial.Cáceres & Monteiro-Filho (2001) found the species most active during the first hours of the night in Curitiba, showing some synchrony with small mammal species that occasionally figure in their diet. Using a spool and line technique in Serra dos Orgãos, Brazil Cunha & Vieira (2005) detected no increase in arboreal behaviour during the wet season when plentiful fruit crops might have been expected to alter the foraging strategy. Juveniles were found to be slightly more arboreal than adults and it was hypothesised that this may be related to their increased vulnerability to ground-based predators. Individuals were observed to reach a maximum height of 20m in the canopy. Locomotion The species is an excellent climber and able to climb vertical tree-trunks, reversing the hind feet and using the claws to grip. Cunha & Vieira (2002) note that Didelphis opossums move on thin limbs even when broader and apparently more stable limbs are available, distributing their weight across all four limbs and using the prehensile tail as a fifth limb. Delciellos & Vieira (2006) studied arboreal locomotion of this species on horizontal branches in PN Serra dos Orgãos, Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. A maximum velocity of 2.49 (+/-0.74) x body length/second was recorded on support branches of 10.16cm diameter, and a minimum velocity of 1.95 (+/-0.07) x body length/second was recorded on support branches of 5.08cm diameter. Minimum number of strides per second was 2.22 (+/-0.05) on support branches of 5.08cm and maximum number of stride lengths per second was 2.93 (+/-0.15) on a flat surface. Range of stride length was from 0.82 to 0.95 x body length. Maximum velocity is reached by increasing stride frequency rather than increasing stride length, this likely being related to maintaining the stability of a large animal on a thin branch being of greater importance than final velocity (Delciellos & Vieira 2007). Delciellos & Vieira (2009) investigated climbing performance of this species on nylon ropes of three diameters 0.6cm, 0.9 and 1.25cm. Respective velocities (stride length x stride frequency) of 0.24 (+/-0.17), 0.36 (+/-0.20) and 0.42 (+/-0.16) were recorded for the three rope diameters. Number of strides per second respectively were 0.80 (+/-0.27), 0.93 (+/-0.19) and 1.01 (+/-0.10) for the three rope diameters. Stride length when related to body length was 0.29 (+/-0.10), 0.38 (+/-0.12) and 0.42 (+/-0.14) respectively. Home Range Cáceres (2003) studied space use and territoriality in a mark-recapture study in Curitiba, southern Brazil. He noted that territories are established in aggregated patterns with low levels of overlap. Four female individuals were responsible for 68% of the 190 recaptures leading to the conclusion that females hold year-round territories. Males were considered migratory or residents of neighbouring forest patches that only occasionally made incursions into the study area. Home range size of males (2.3-2.7ha) were larger than those of females (0.6-1.7ha). Additionally larger range size was correlated to greater age and body mass in females. Loretto & Vieira (2005) demonstrated that males used larger areas in a less intensive manner during the breeding season and that females used larger areas less intensively during the dry season than they did during the wet season. Vieira & Cunha (2008) found home range size and intensity of use to be correlated to body mass. Female territories were estimated to overlap by 15% in the non-breeding season, but this figure reduced to 6% during the breeding season. Davis (1945) had earlier found that males wander more than females during a study of the species in Teresópolis, Brazil and that individual territories overlap. Loretto & Vieira (2005) correlated movements of males with reproductive effort whilst movement of females was associated with resource availability. Greater mobility of males can lead to greater oscillations in their density when compared with females (Mendel et al 2008). Gentile & Cerquiera (1995) performed a mark-recapture study on this species in the Brazilian restinga at Barra de Maricá, Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. Sampling a 4ha site they found that 61% of movements were less than 60m from the original capture site. They considered the species to be highly mobile with local populations part of a metapopulation with a range not restricted to the sampling area. Gentile et al (2004) correlated population density with litter fall with a 6 to 7 month time lag in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Enemies On the B2-277 bordering PN Iguacu in Paraná State, Brazil D. aurita and D. albiventris represented 16.2% of the mamals hit by cars. (Lima & Obara 2004). Parasites Limardi (2006) notes the following ectoparasites of this species in Brazil: Siphanoptera Ctenocephalides felis (Pulicidae). Acari: Metastigmata Ixodes loricatus, Amblyomma striatum (Ixodidae). Acari: Mesostigmata Bdellonyssus sp., Ornithonyssus wernecki and O.brasiliensis (Macronyssidae). Acari: Astigmata Didelphilichus serrifer (Atopomelidae). Thatcher (2006) lists the following endoparasites of this species in Brazil: Cestoda Mathevotaenia bivittata (Anoplocephalidae). Nematoda Dracunculus fuelleborni (Dracunculidae); Gongelonemoides marsupialis (Gongylonematidae); Dipetalonema pricei (Oncocercidae); Thominx auritae (Trichuridae); Travassostrongylus callis, T.orloffi, Viannaia viannai, V.hamata and V.pusilla (Trichostrongylidae). Acanthocephala Oligacanthorhynchus microcephala (Oligacanthorhynchidae). Longevity Kajin et al (2008) found the longest lived individual in their nine-year study at PN Serra dos Orgãos, Brazil to have survived 600 days. The species experiences high mortality whilst in the pouch and shortly after weaning. Life expectancy thus increases after weaning, but declines again through life. Few adults survive more than one breeding season and population turnover is high.

VOC: No information.

HUM: The species is hunted for sport and food in some areas of Brazil, and as with other Didelphis opposums is persecuted for its supposed taste for domestic poultry (though such predation has not been proved in this species - Massoia et al 2006). Limited commercial hunting for the fur trade has little impact on the species.

CON: Globally considered to be of Low Risk Least Concern by the IUCN, click here to see their latest assessment of the species because of its wide distribution, occurrence in protected areas and large population. The Centro de Datos de Conservación in Paraguay consider the species to be in danger in Paraguay giving it the code N2. The species is not listed by CITES. In Paraguay the distribution is confined to remaining patches of Atlantic Forest in a relatively small area of the north-central and northeastern Orient. Fragmentation of the Atlantic Forest has been severe in this area and the species has undoubtedly declined as a result. It is considerably less numerous than the related Didelphis albiventris (which replaces it) and it does not tolerate the same degree of human disturbance of its habitat - though it apparently does so in Brazil in areas where D.albiventris does not occur. Typically the two species do not occur together and where they do this species is found in denser, more forested habitat, whilst D.albiventris is in more open and disturbed areas. Mendel et al (2008) found that the population density of females depends to some extent on litterfall and the associated macroarthropods that occur within it, with a delay of 6 to 7 months after the initial fall during which time the arthropod and hence opossum populations respond to the increased litter levels. Moura et al (in press) consider the species a key intraguild predator in Brazil, with its presence having a direct effect on the small mammal communities that share its habitat. The species is probably of national conservation concern given its dependence on undisturbed forest and the rapid expansion of Didelphis albiventris into perturbed areas.

Citable Reference: Smith P (2009) FAUNA Paraguay Online Handbook of Paraguayan Fauna Mammal Species Account 33 Didelphis aurita.

Last Updated: 30 June 2009.

References:

Allen JA 1902 - A Preliminary Study of the South American Opossums of the Genus Didelphis - Bulletin AMNH 16: p149-188.

Astúa de Morães D, Lemos B, Finotti R, Cerquiera R 2001 - Supernumerary Molars in Neotropical Opossums (Didelphimorphia, Didelphidae) - Mammalian Biology 66: p193-203.

Astúa de Morães D, Moura RT, Grelle CEV, Fonseca MT 2006 - Influence of Baits, Trap Type and Position for Small Mammal Capture in a Brazilian Lowland Atlantic Forest - Bol. Mus. Biol. Mello. Leitão 19: p19-32.

Astúa de Morães D, Santori RT, Finotti R, Cerquiera R 2003 - Nutritional and Fibre Contents of Laboratory-established Diets of Neotropical Opossums (Didelphidae) p225-233 in Jones M, Dickman C, Archer M Predators with Pouches: The Biology of Carnivorous Marsupials - CSIRO Publishing, Australia.

Ávila-Pires FD de 1968 - Tipos de Mamíferos Recientes no Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro - Arquivos Museu Nacional 53: p161-192.

Azara F de 1801 - Essais sur l´Histoire Naturelle des Quadrupèdes de la Province du Paraguay - Charles Pougens, Paris.

Bertoni A de W 1914 - Fauna Paraguaya. Catálogos Sistemáticos de los Vertebrados del Paraguay. Peces, Batracios, Reptiles, Aves y Mamíferos Conocidos hasta 1914 in Bertoni MS Descripción Física y Económica del Paraguay - M.Brossa, Asunción.

Brown BE 2004 - Atlas of New World Marsupials - Fieldiana Zoology 102.

Cáceres N 2003 - Use of the Space by the Opossum Didelphis aurita Wied-Neuwied (Mammalia Marsupialia) in a Mixed Forest Fragment of Southern Brazil - Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 20: p315-322.

Cáceres NC, Monteiro Filho EL de A 1999 - Tamanho Corporal em Populacões Naturais de Didelphis (Mammalia: Marsupialia) do Sul do Brasil - Revista Brasileira de Biologia 57: p461-469.

Cáceres NC, Monteiro Filho EL de A 2001 - Food Habits, Home Range and Activity of Didelphis aurita (Mammalia Marsupialia) in a Forest Fragment of Southern Brazil - Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment 36: p85-92.

Cáceres NC, Monteiro-Filho EL de A 2007 - Germination in Seed Species Ingested by Opossums: Implications for Seed Dispersal and Forest Conservation - Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology 50: p921-928.

Cannevari M, Vaccaro O 2007 - Guía de Mamíferos del Sur de América del Sur - LOLA, Buenos Aires.

Carvalho FMV de, Delciellos AC, Vieira MV 2000 - Medidas Externas dos Miembros de Marsupiais Didelfidios: Uma Comparação com Medidas do Esqueleto Pós-Craniano - Boletim do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro 438.

Carvalho FMV de, Pinheiro PS, Fernández FAS, Nessimian JL 1999 - Diet of Small Mammals in Atlantic Forest in Southeastern Brazil - Revista Brasileira de Zoociencias 1: p91-101.

Ceotto P, Finotti F, Santori R, Cerqueira R 2009 - Diet Variation of the Marsupials Didelphis aurita and Philander frenatus (Didelphimorphia: Didelphidae) in a Rural Area of Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil - Mastozoologia Neotropical 16.

Cerqueira R 1985 - The Distribution of Didelphis in South America (Polyprotodontia, Didelphidae) - Journal of Biogeography 12: p135-145.

Cerqueira R, Lemos B 2000 - Morphometric Differentiation Between Between Neotropical Black-eared Opossums Didelphis marsupialis and Didelphis aurita (Didelphimorphia, Didelphidae) - Mammalia 64: p319-327.

Chebez JC 1996 - Fauna Misionera - LOLA, Buenos Aires.

Cope ED 1889 - On the Mammalia Obtained by the Naturalist Exploring Expedition to Southern Brazil - American Naturalist 23: p128-150.

Cunha AA, Vieira MV 2002 - Support Diameter, Incline and Vertical Movements of Four Didelphid Marsupials in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil - Journal of Zoological Society of London 258: p419-426.

Cunha AA, Vieira MV 2005 - Age, Season and Arboreal Movements of the Opossum Didelphis aurita in an Atlantic Rainforest of Brazil - Acta Theriologica 50: p551-560.

Davis DE 1945 - The Home Range of Some Brazilian Mammals - Journal of Mammalogy 26: p119-127.

Delciellos AC, Vieira MV 2006 - Arboreal Walking Performance in Seven Didelphid Marsupials as an Aspect of Their Fundamental Niche - Austral Ecology 31: p449-457.

Delciellos AC, Vieira MV 2007 - Stride Lengths and Frequencies of Arboreal Walking in Seven Species of Didelphid Marsupials - Acta Theriologica 52: p101-111.

Delciellos AC, Vieira MV 2009 - Allometric, Phylogenetic and Adaptive Components of Climbing Performance in Seven Species of Didelphid Marsupials - Journal of Mammalogy 90: p104-113.

Emmons LH 1999 - Mamíferos de los Bosques Húmedos de América Tropical - Editorial FAN, Santa Cruz.

Esquivel E 2001 - Mamíferos de la Reserva Natural del Bosque Mbaracayú, Paraguay - Fundación Moises Bertoni, Asunción.

Gardner AL 2007 - Mammals of South America Volume 1: Marsupials, Xenarthrans, Shrews and Bats - University of Chicago Press.

Gentile R, D´Andrea PS, Cerqueira R 1995 - Age Structure of Two Marsupial Species in a Brazilian Restinga - Tropical Ecology 11: p679-682.

Gentile R, D´Andrea PS, Cerqueira R, Maroja LS 2000 - Population Dynamics and Reproduction of Marsupials and Rodents in a Brazilian Rural Area: A Five-year Study - Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment 35: p1-9.

Gentile R, Cerqueira R 1995 - Movement Patterns of Five Species of Small Mammals in a Brazilian Restinga - Tropical Ecology 11: p671-677.

Gentile R, Finotti R, Rademaker V, Cerqueira R 2004 - Population Dynamics of Four Marsupials and its Relation to Resource Production in the Atlantic Forest of Southeastern Brazil - Mammalia 68: p109-119.

Gmelin JF 1788 - Caroli a Linné ..... Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae Secundum Clases Ordines, Genera, Species cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis - Editio Decima Tertia, Aucta, Reformata. Lipisiae: Georg Emanuel Beer.

Grelle CE de V, García QS 1999 - Dispersion of Cecropia hololeuca by the Common Opossum Didelphis aurita in Atlantic Forest, Southeastern Brazil - Revue. Ecol. Terre Vie 54: p327-332.

Ihering H von 1892 - Os Mamíferos do Rio Grande do Sul - Annuario do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul para o Anno 1893 de Graciano A de Azambuja p96-123.

Kajin M, Cerqueira R,Vieira MV, Gentile R 2008 - Nine Year Demography of the Black-eared Opossum Didelphis aurita (Didelphimorphia: Didelphidae) Using Life Tables - Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 25: p206-213.

Lemos B, Marriog G, Cerqueira R 2001 - Evolutionary Rate and Morphological Stasis in Large-bodied Opossum Skulls (Didelphimorphia: Didelphidae) - Journal of Zoology 255: p181-189.

Liais E 1872 - Climats, Géologie, Faune et Géographie Botanique du Brésil - Garnier Frères, Paris.

Lima SF, Obara AT 2004 - Levantamento de Animais Silvestres Atropelados na BR-277 às Margens do Parque Nacional do Iguaçu - Subsídios ao Programa Multidisciplinar de Proteção à Fauna.

Limardi PM 2006 - Os Ectoparasitos de Marsupiais Brasileiros p27-52 in Cáceres NC, Monteiro-Filho ELA Os Marsupiais do Brasil:Biologia, Ecologia e Evolução - Editora UFMS, Campo Grande.

Loretto D, Vieira MV 2005 - The Effects of Reproductive and Climatic Seasons on Movements in the Black-eared Opossum (Didelphis aurita Wied-Neuwied 1826) - Journal of Mammalogy 86: p287-293.

Mares MA, Braun JK 2000 - Systematics and Natural History of Marsupials from Argentina p23-45 in Reflections of a Naturalist: Papers Honoring Professor Eugene D Fleharty, Fort Hays Studies Special Issue 1.

Massoia E, Chebez JC, Bosso A 2006 - Los Mamíferos Silvestres de la Provincia de Misiones, Argentina - DVD-ROM.

Massoia E, Forasiepi A, Teta P 2000 - Los Marsupiales de la Argentina - LOLA, Buenos Aires.

Matschie P 1916 - Bemerkungen über die Gattung Didelphis L. - Sitzungsber. Gesells. Naturf. Freunde Berlin 1916: p259-272.

Mendel SM, Vieira MV, Cerqueira R 2008 - Precipitation, Litterfall and the Dynamics of Density and Biomass in the Black-eared Opossum Didelphis aurita - Journal of Mammalogy 89: p159-167.

Miranda-Ribeiro A 1935 - Fauna de Terezopolis - Boletim Museu Nacional Rio de Janeiro 11: p1-40.

Moura MC, Caparelli AC, Freitas SR, Vieira MV 2005 - Scale Dependent Habitat Selection in Three Didelphid Marsupials Using the Spool-and-line Technique in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil - Journal of Tropical Ecology 21: p337-342.

Moura MC, Cerqueira R, Vieira MV 2009 - Occasional Intraguild Predation Structuring Small Mammal Assemblages: The Marsupial Didelphis aurita in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil - Austral Ecology IN PRESS

Myers P, Espinosa R, Parr CS, Jones T, Hammond GS, Dewey A 2006 - The Animal Diversity Web (online). Accessed December 2007.

Rademaker V, Cerqueira R 2006 - Variation in the Latitudinal Reproductive Patterns of the Genus Didelphis (Didelphimorphia: Didelphidae) - Austral Ecology 31: p337-342.

Redford KH, Eisenberg JF 1992 - Mammals of the Neotropics: Volume 2 The Southern Cone - University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Santori RT, Astúa de Moraes D, Cerqueira R 1995 - Diet Composition of Metachirus nudicaudatus and Didelphis aurita (Marsupialia, Didelphoidea) in Southeastern Brazil - Mammalia 59: p511-516.

Santori RT, Astúa de Moraes D, Cerqueira R 2004 - Comparative Gross Morphology of the Digestive Tract in Ten Didelphidae Marsupial Species - Mammalia 69: p27-36.

Santori RT, Cerqueira R, da Cruz Cleske D 1995 - Anatomia e Eficiência Digestiva de Philander opossum e Didelphis aurita (Didelphimorphia, Didelphidae) em Relação ao Hábito Alimentar - Revista Brasileira de Biologia 55: p323-329.

Temminck CJ 1824 - Deuxième Monographie sur le Genre Sarigue - Didelphis (Linn.) in Monographies de Mammalogie ou Description de Quelques Genres de Mammifères dont les espèces ont été Observeés dans les Différens Musées de l´Europe - G.Dufour et E d´Ocogne, Paris.

Thatcher VE 2006 - Os Endoparasitos dos Marsupiais Brasileiros p53-68 in Cáceres NC, Monteiro-Filho ELA Os Marsupiais do Brasil:Biologia, Ecologia e Evolução - Editora UFMS, Campo Grande.

Trouessart EL 1898 - Catalogus Mammalium tam Viventium quam Fossilium. Fasciculus V: Sirenia, Cetacea, Edentata, Marsupialia, Allotheria, Monotremata - R.Friedländer & Sohn, Berolini.

Tyndale-Biscoe CH, MacKenzie RB 1976 - Reproduction in Didelphis marsupialis and D.albiventris in Colombia - Journal of Mammalogy 57: p249-265.

Vieira MV 1997 - Body Size and Form in Two Neotropical Marsupials, Didelphis aurita and Philander opossum (Marsupialia: Didelphidae) - Mammalia 61: p245-254.

Vieira MV, Cunha AdeA 2008 - Scaling Body Mass and Use of Space in Three Species of Marsupials in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil - Austral Ecology 33: p872-879.

Villalba R, Yanosky A 2000 - Guía de Huellas y Señales: Fauna Paraguaya - Fundación Moises Bertoni, Asunción.

Wagner JA 1843 - Die Säugthiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur mit Beschreibungen von Dr Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber. Supplementband. Dritter Abtheilung: Die Beutelthiere und Nager (Erster Abschnitt) Erlangen: Expedition das Schreber´schen Säugthier- und des Esper´sschen Schmetterlingswerkes und in Comission der Voss´schen Buchhandlung in Leipzig.

Wied-Neuwied MP zu 1826 - Beiträage zue Naturgeschichte von Brasilien. Verzeichniss der Amphibien, Säugthiere un Vögel, welche auf einer Reise Zwischen dem 13ten dem 23sten Grade Südlicher Breite im Östlichen Brasilien Beobachtet Wurden II Abtheilung Mammalia, Säugthiere - Gr. HS priv. Landes Industrie Comptoirs, Weimar.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special thanks to Juan Carlos Chebez for providing important literature and Nilton Cáceres for very kindly reviewing texts and providing a copy of his book Os Marsupiais do Brasil.

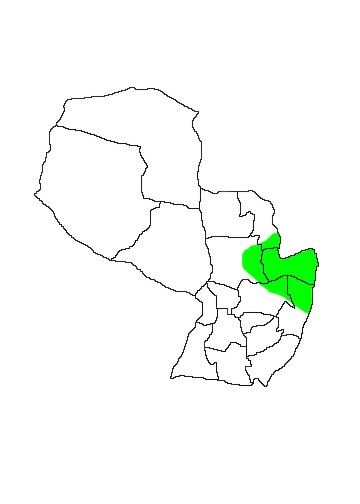

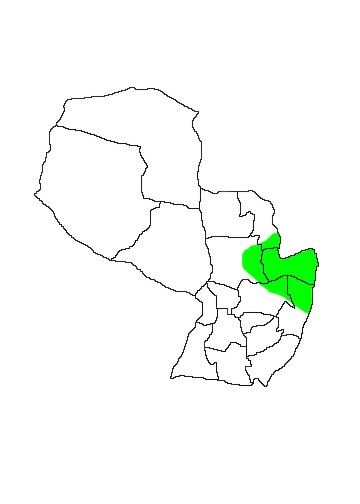

MAP 33:

Didelphis aurita

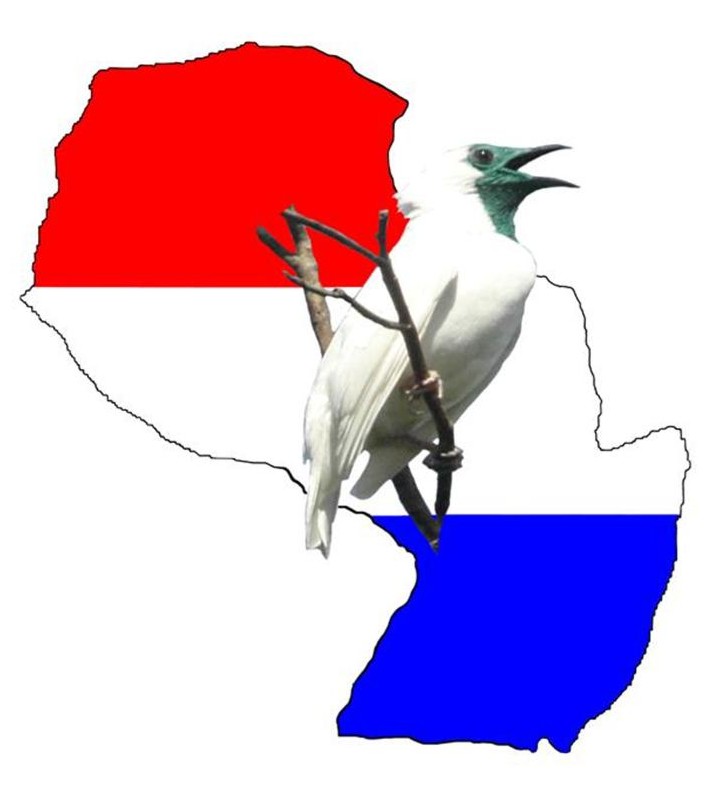

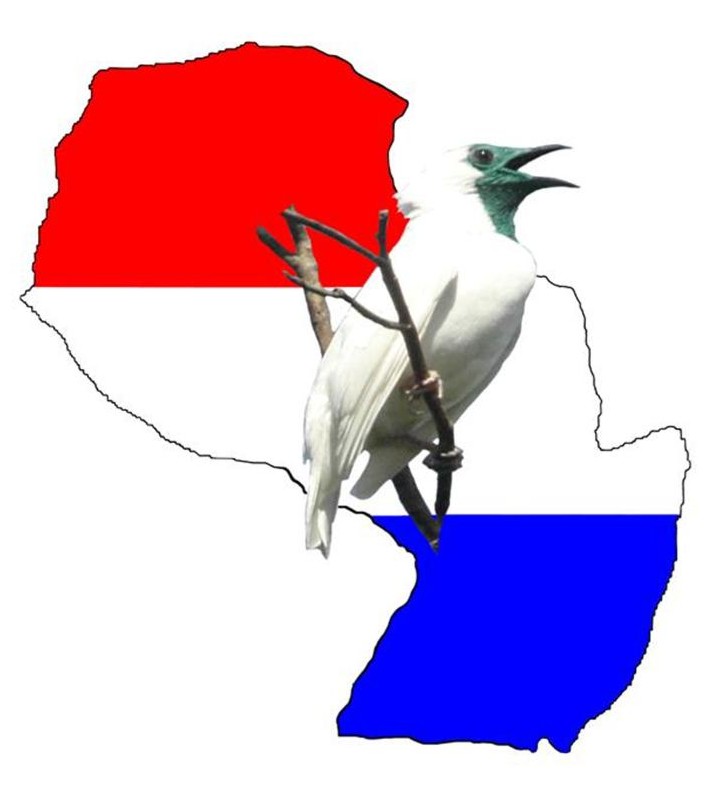

Didelphis aurita Wied-Neuwied, 1826 Image Gallery

TAX: Class Mammalia; Subclass Theria; Infraclass Metatheria; Order Didelphimorphia; Family Didelphidae; Subfamily Didelphinae, Tribe Didelphini (Myers et al 2006, Gardner 2007). The genus Didelphis was defined by Linnaeus, 1758. There are five known species according to the latest revision (Gardner 2007) two of which are present in Paraguay. The generic name Didelphis is from the Greek meaning "double womb", and aurita is derived from the Latin for "long-eared". The species is monotypic (Gardner 2007). Didelphis aurita was long considered conspecific with the Northern Black-eared Opossum Didelphis marsupialis Linnaeus 1758, but the distributions are disjunct, with this species very tightly associated with the Atlantic Forest biome of eastern Brazil, eastern Paraguay and northern Argentina. Cerqueira (1985) considered the two forms to be part of a superspecies complex, and Cerqueira & Lemos (2000) demonstrated clear morphometric differences between the two populations to support their specific status. Lemos, Marriog & Cerqueira (2001) demonstrated a Pleistocene cladogenesis through rapid differentiation of the two species. The name Didelphis azarae Temminck 1824 was clearly applicable to this species given that the written description specifically mentions black ears. However this name has been misapplied almost since its inception in reference to Didelphis albiventris, and though it predates Wied-Neuwied´s name Didelphis aurita, the confusion caused by its misapplication means that D.aurita is now the most frequently used name in the interests of maintaining stability (Gardner 2007). Synonyms adapted from Gardner (2007):

Didelphis azarae Temminck 1824:30. Type locality "Bresil".

D[idelphys] marsupialis Wied-Neuwied 1826:387. In part. Name combination.

D[idelphys] aurita Wied-Neuwied 1826:395. Type locality "Villa Viçosa an Flusse Peruhype", Bahía, Brazil.

Didelphys azarae JA Wagner 1843:38. Name combination.

Didelphys cancrivora JA Wagner 1843:41. Not D.cancrivora Gmelin (1788).

Gamba aurita var. brasiliensis Liais 1872:329. Implied type locality Brazil.

Didelphys marsupialis aurita Cope 1889:129. Name combination.

Didelphis koseritizi Ihering 1892:99. Type locality "Colonia do Novo Mundo" Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

[Didelphys (Marmosa)] koseriti Trouessart 1898:1240. Name combination and incorrect spelling.

[Didelphys (Didelphys) marsupialis] aurita Trouessart 1898:1234. Name combination.

Didelphis masrupialis cancrivora Bertoni 1914:68. Name combination.

[Didelphis (Didelphis)] leucoprymnus Matschie 1916:268. Nomen nudum.

Didelphis aurita longipilis A.Miranda-Ribeiro 1935:35. Type locality "Côlonia Alpina" 16km N of Teresópolis, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Didelphis aurita malanoidis A.Miranda-Ribeiro 1935:40. Type locality "Therezópolis" restricted to Côlonia Alpina, 16km N of Teresópolis, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil by Ávila-Pires (1968).

Didelphis aurita longigilis Ávila-Pires 1968:169. Incorrect spelling.

ENG: Southern Black-eared Opossum, Black-eared Opossum (Redford & Eisenberg 1992, Canevari & Vaccaro 2007), Big-eared Opossum (Gardner 2007), Gambá (Gardner 2007), Common Opossum (Esquivel 2001), Brazilian Common Opossum (IUCN 2008), Southern Common Opossum (Astúa de Morães et al. 2003).

ESP: Comadreja orejuda, Zarigüeya orejuda (Canevari & Vaccaro 2007), Zarigüeya común del sudeste (Emmons 1999), Comadreja grande (Redford & Eisenberg 1992), Comadreja de orejas negras (Chebez 1996, Massoia et al 2000), Mbicuré orejudo (Chebez 1996, Massoia et al 2000), Mbicuré negro (Chebez 1996), Mbicuré cangrejero (Chebez 1996, Massoia et al 2000), Comadreja negra (Massoia et al 2006).

GUA: M Mykurê hu (Villalba & Yanosky 2000), Mbicuré-hú (Chebez 1996, Massoia et al 2000, Canevari & Vaccaro 2007), Ac Guné (Villalba & Yanosky 2000), Ac Ngure (Esquivel 2001), Mykure (Esquivel 2001), Mbihkurê (Chebez 1996).

DES: The smaller of the two Didelphis opossums this species is characterised by its blackish or greyish pelage and golden-buff facial and base colour. Dorsal pelage greyish-white variably variegated with black so that it appears more or less dark. Long guard hairs (80-100mm long) are white to the base and are particularly long on the rump giving a shaggy appearance. Underfur golden-buff basally on the mid back, becoming more yellow-brown basally on the flanks and blackish on the apical third to half throughout. Ventral pelage shorter and woollier, brownish-white basally and tipped blackish-brown with scattered golden-buff hairs. Hairs bordering the marsupium darker brown to blackish-chestnut. Indistinct whitish patch on mid-chest. The rostrum is slightly elongated and somewhat triangular. Chin and throat golden-buff with hairs tipped dark brown except for on the lower throat. Head pattern indistinct with dark blackish median line and patches around the eyes offset against a golden-buff background of the rest of the head. Median line begins between the eyes and widens towards the nape. Eye patches begin halfway between the nose and eyes and reach almost to the base of the ears, being less well-defined and broader behind the eyes than in front. Head markings are typically more distinct on younger specimens. Ears are large, rounded and blackish. Limbs black, including the semi-naked toes. Feet are broad and claws are long. Tail slightly shorter than head and body length, furred at the base and naked and bicoloured for the rest of its length. Black on the basal half and flesh-coloured on the distal half. This species is extremely variable in the extent of the dark colouration with some specimens almost black and others paler and dark grey in colour. There is also age variation in colouration, the youngest individuals typically having the strongest facial pattern and whitish or flesh-coloured ears, at which time they may be mistaken for juvenile Didelphis albiventris, though the base colour is always yellowish and never white. Ears darken with age, with the basal area assuming dark colouration before the tips. Young individuals may also show less black at the base of the tail than adults. (Allen 1902). CR: Cerqueira & Lemos (2000) gave the following skull measurements for both sexes of this species: Greatest Skull Length male 104.39mm (+/-8.82) female 95.13mm (+/-5.73); Condylobasal Length male 101.04mm (+/-7.52) female 93.26mm (+/-5.20); Length of Mandible male 84mm (+/-6.83) female 77.02mm (+/-4.61); Length of Nasals male 50.63mm (+/-4.63) female 46.38mm (+/-3.10); Greatest Nasal Width male 15.72mm (+/-1.58) female 14.22mm (+/-1.25); Length of Palate male 61.61mm (+/-3.84) female 58.66mm (+/-2.88); Width of Palatal Shelf male 17.16mm (+/-1.30) female 16.98mm (+/-1.43); Interorbital Constriction male 21.88mm (+/-2.59) female 19.03mm (+/-1.41); Postorbital Constriction male 11.38mm (+/-0.51) female 11.66mm (+/-0.48); Width of Rostrum Across Frontals male 18.43mm (+/-2.13) female 16.31mm (+/-1.30); Width of Rostrum Across Jugals male 27.15mm (+/-2.67) female 24.64mm (+/-1.78); Zygomatic Width male 55.92mm (+/-5.46) female 48.21mm (+/-3.37); Width Across Molars male 29.88mm (+/-1.51) female 29.37mm (+/-1.19); Width Across Canines male 19.81mm (+/-2.05) female 16.97mm (+/-1.28); Width of Brain Case male 28.14mm (+/-2.28) female 25.85mm (+/-1.48). DF: I5/4 C1/1 P 3/3 M 4/4 = 50. Cerqueira & Lemos (2000) gave the following measurements for both sexes of this species: Length of Maxillary Tooth Row male 41.49mm (+/-1.88) female 39.95mm (+/-1.51); Length of Upper Molar Row male 19.11mm (+/-0.95) female 18.75mm (+/-0.64); Length of Lower Molar Row male 21.42mm (+/-1.03) female 21.21mm (+/-0.82). Tyndale-Biscoe & MacKenzie (1976) summarised ageing in Didelphis opossums based on dental wear by defining 7 age classes as follows: Dental Class 1: (<4 months) dP3 M1 no cusp wear; Dental Class 2: (4-6 months) dP3 M2 no cusp wear; Dental Class 3: (5-7 months) dP3 M3 no cusp wear; Dental Class 4: (6-11 months) P3 M3 no cusp wear; Dental Class 5: (9-16 months) P3 M4 no cusp wear; Dental Class 6: (15-23 months) P3 M4, cusp wear on P3 and M1-2; Dental Class 7: (>22 months) P3 M4, cusp wear on P3 and M3-4. Astúa de Morães et al. (2001) describe supernumerary molars erupting behind on each side of the superior row in specimen AMNH 133034. Tooth shape is molariform on both sides, though slightly reduced and with a crown pattern resembling a normal M4 on the right side. CN: 2n=22.

TRA: Didelphis prints are characteristically wider than they are long with a notably uneven appearance, especially on the hindfoot which shows fore toes displaced to one side and the opposable thumb on the other side. The tail being dragged behind the body often leaves an impression. FP: 4.3 x 5cm; HP: 3.2 x 6cm; PA: 12cm. (Villalba & Yanosky 2000, Massoia et al 2009).

MMT: The smaller of the two Paraguayan Didelphis. Allen (1902) gave the following measurements for 3 adult males and six adult females from Brazil: TL: male 77.77cm (range 74.5-80.6cm) female 74.42cm (range 67.8-77cm); HB: male 41.7cm (range 40.5-42.6cm) female 39.38cm (range 35.8-41cm); TA: male 36.07cm (range 34-38cm) female 35.36cm (range 32-38.8cm); FT: male 5.43cm (range 4.8-6.1cm) female 5.38cm (range 4.1-6.1cm); EA: male 4.8cm (range 4.6-5cm) female 5.15cm (range 3.9-6cm). Vieira (1997) gave the following mean measurements for the species (n=25): HB: 38.28cm; TA: 31.72mm; FT: 4.73cm; Foot 3.96cm; Width Claw 0.47cm; Arm 6.66cm; Forearm 7.42cm; Leg 7.72cm; Foreleg 8.47cm; Forelimb 14.08cm; Hindlimb 16.16cm; WT: 1098g (range 670-1560g). He noted that the relatively long forelimbs, long claws and broad feet were associated with a terrestrial/arboreal existence and a walking means of locomotion. More ponderous animals require sturdier forelimbs when climbing. The following mean post-cranial measurements were noted by Carvalho et al (2000) for Brazilian specimens (n=5): Ulna 67.3mm; Forearm 78.7mm; Humerus 59mm; Tibia 72.2mm; Foreleg 95.1mm; Femur 70.2mm.

Cáceres & Monteiro-Filho (1999) noticed a correlation between head length and age class, and stated that the measurement may be used to estimate body length. Mass was noted to increase during autumn in preparation for the winter season with fewer resources. Males undergo more rapid growth than females and are typically larger and heavier. Adult size is reached about 10 months. They gave the following external body measurements for differing age classes of males and females from southern Brazil:

Young (6-7 months old, dental class 3): Head: male 11.0cm female 10.4cm (+/-0.3); Body: male 26.7cm female 26cm (+/-2.3); FT: male 5.2cm female 4.9cm (+/-0.2); WT: male 760g female 726g (+/-126).

Subadult (7-11 months old, dental class 4): Head: male 12.8cm female 10.9cm (+/-0.1); Body: male 30cm female 29.7cm (+/-0.3); FT: male 5.7cm female 5.1cm (+/-0.1); WT: male 1250g female 900g (+/-80).

Young adult (10-16 months old, dental class 5): Head: male 13.3cm (+/-0.4) female 11.8cm (+/-0.3); Body: male 35.8cm (+/-2.9) female 32.4cm (+/-1.5); FT: male 6cm (+/-0.3) female 5.5cm (+/-0.2); WT: male 1643g (+/-158) female 1116g (+/-95).

Adult (15-23 months old, dental class 6): Head: male 14.6cm (+/-0.1) female 12.5cm (+/-0.1); Body: male 38.5cm (+/-1.1) female 33.5cm (+/-0.6); FT: male 6.2cm (+/-0.3) female 5.6cm (+/-0.1); WT: male 1793g (+/-135) female 1303g (+/-133).

Senile adult (>22 months old, dental class 7): Head: female 13.1cm (+/-0.3); Body: female 34.4cm (+/-0.1); FT: female 5.7cm (+/-0.1); WT: male 1643g (+/-158) female 1353g (+/-30).

SSP: The smaller representative of the genus Didelphis in Paraguay, these are large opossums with pointed snouts, dense, shaggy pelage and large, rounded ears. This species could only be confused with Didelphis albiventris but is easily separated on account of its much darker, almost blackish body colouration, dark blackish ears (as opposed to pinkish-white in the "White-eared Opossum") and its strict preference for humid forested environments - as opposed to the catholic habitat preference of the White-eared Opossum which is frequently in dry, scrubby habitats and even in areas of human habitation. Furthermore note that the black head markings are much less distinct in this species and that the ground colour is golden-buff as opposed to pure white. This latter character is the most reliable when distinguishing juveniles, as young individuals of this species may have more or less pale-tipped ears (the ears being wholly pale in the youngest individuals) and more strongly-marked facial patterns than adults, but they never have a white ground colour to the head as in D.albiventris.

DIS: Distributed in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay. In Argentina they are confined to Provincia Misiones (Mares & Braun 2000). There is an isolated population in north-west Brazil in Alagoas and Pernambuco. In Paraguay the distribution is limited to central-eastern Paraguay and is greatly reduced following the disappearance of much of the Alto Paraná Atlantic Forest. The species is known to occur in Departamentos Alto Paraná, Caazapá, eastern San Pedro, northern Caaguazú and southern Amambay (Brown 2004, Esquivel 2001, Gardner 2007).

HAB: An Atlantic Forest endemic species, this species is confined to primary and secondary humid forests where it is frequently found in the vicinity of streams or waterways. In Brazil it also occurs in Araucaria forests. The species is able to tolerate some degree of human interference in its habit, but shows much lesser affinity for areas of human habitation than Didelphis albiventris.(Gardner 2007). Moura et al (2005) found that the species showed an affinity for rocky areas in PN Serra dos Orgãos, Brazil.

ALI: Omnivorous, opportunistic and scansorial. Fecal samples of two individuals at Poço das Antas, Brazil contained invertebrates from the orders Orthoptera, Arachnida, Coleoptera, Diptera and Hymenoptera, and some unidentified seeds (Carvalho et al 1999). Given its efficient digestive rates, this species is an important disperser of Atlantic Forest plants with the bulk of foods consumed passing through the digestive system within 24 hours (Grelle & García 1999). Cáceres & Monteiro-Filho (2007) examined germination rates of seeds consumed by Didelphis opposums in southern Brazil, finding that germination rates of seeds that had passed through opossum guts were similar to those of control groups for thirteen species of pioneer plants, with the exception of Rubus rosifolius which required gut passage for germination. Fruits of Solanaceae, Cecropiaceae, Rosaceae, Myrtaceae, Moraceae, Rhamnaceae, Cucurbitaceae, Flacourtiaceae, Passifloraceae, Piperaceae and Araceae are consumed and effectively dispersed by this species (Cunha & Vieira 2005). Cáceres (2003) noted that the consumption of Solanum sanctaecatharinae increased greatly when the plant was in fruit in Curitiba, southern Brazil. Grelle & García (1999) noted that the fruits of Cecropia hololeuca are consumed from the ground rather than taken directly from the trees. Moura et al (in press) consider the species an intraguild predator and though it rarely preys on small mammals its presence is enough to promote avoidance of it by other small mammals. Santori et al (1995) studied fecal samples from the dry restinga of Brazil and considered the species omnivorous and opportunistic with a broad dietary range. Of 52 fecal samples 100% contained invertebrates, 30.8% contained vertebrate remains and 53.8% contained seeds. Of the sixteen fecal samples containing vertebrate remains, two contained unidentified mammal remains, two contained remains of the rodent Akodon cursor and one an unidentified bird. Thirteen samples contained the Tropidurid lizard Tropidurus torquatus, five a species of Skink Mabuya sp. and two an unidentified reptile. In order of prevalence the following invertebrate groups were found in samples: Blattaria 67.3%, Hymenoptera (Formicidae) 65.4%, Orthoptera (Tettigonidae) 30.8%, unidentified Coleoptera 26.9%, Diplopoda 23.1%, Diptera pupae 17.3%, Chilopoda 15.4%, Myriapoda 7.7% and Coleoptera (Scarabaeidae) 7.7%. The remaining groups were all present in one sample, representing 1.9% of the total sample: Mollusca, Crustacea, Araneidae, Acari, Opiliones, Scolopendramorpha, Unidentified Orthoptera, Coleoptera (Curculionidae), Coleoptera (Histeridae), Hemiptera, Unidentified Hymenoptera, Hymenoptera (wasps), Isoptera and Dermaptera. The presence of Dipteran pupae was considered a possible indication of scavenging behaviour, while the presence of ants antermites was considered to be the result of opportunistic feeding as no nest remains were found in the faeces. Seeds of the following species were found in order of prevalence: Anthurium harrissii (Araceae) 23.1%, Unidentified seeds 21.2%, Paullinia weinmanniaefolia (Sapindaceae) 11.5%, Pilosocereus sp. (Cactaceae) 9.6%, Passiflora sp (Passifloraceae) 5.8%, Rhypsalis sp. (Cactaceae) 3.8%, Psidium sp (Myrtaceae) and unidentified Solanaceae 1.9%. Fruit consumption was seen as a way of increasing water intake in this dry environment. Cáceres & Monteiro-Filho (2001) consider the species an insectivorous-omnivorous species. Working in Curitiba, Paraná State, Brazil they examined 157 fecal samples (65 in dry season, 92 in wet season) of trapped individuals and found that 100% contained invertebrates, 59% contained vertebrate remains and 78% contained fruit. Strong seasonality was discovered in some food items with some vertebrates and most fruits consumed during the wet season. The following results were obtained for the dry season (d) and wet season (w) respectively, with the value referring to the number of scats in which the item was present: Vertebrates (d45% w70%) included birds mainly Turdus rufiventris 27% (d14% w37%), mammals 15% (d18% w12%), reptiles mainly Liotyphlops beui 14% (d2% w23%) and fish 1% (d2% w0%) with unidentified bones representing 11% (d9% w12%). Predictable seasonality in reptile predation represents its seasonal availability. Invertebrates (d100% w100%) included Diplopoda 76% (d89% w67%), Opiliones 69% (d72% w67%), Coleoptera mainly Scarabaeioidea 72% (d57% w83%), Hymenoptera mainly Formicidae 33% (d32% w32%), Gastropoda 28%(d20% w34%), Decapoda 26% (d28% w25%), Blattaria 24% (d17% w28%), Isopoda 13% (d17% w10%), Orthoptera 10% (d5% w14%), Lepidoptera larvae 6% (d14% w1%) and other invertebrates 10% (d12% w8%). Fruit (d58% 92%) included: Passiflora actinia 39% (Passifloraceae d25% w49%), Solanum sanctaecatharinae 23% (Solanaceae d22% w24%), Piper gaudichaudianum 21% (Piperaceae d0% w36%), Solanum granulosoleprosum 13% (Solanaceae d2% w21%), Melothria cucumis 11% (Cucurbitaceae d6% w14%), Cyphomandra corymbiflora 6% (Solanaceae d5% w7%), Solanum swartzianum 6% (Solanaceae d0% w11%), Morus nigra 6% (Moraceae d0% w11%), Vassobia breviflora 4% (Solanaceae d0% w8%), Rubus rosifolius 4% (Rosaceae d0% w7%), Cucumis sp. 3% (Cucurbitaceae d6% w1%), Psidium guajava 3% (Myrtaceae d0% w4%), Erythroxylum deciduum 3% (Erythroxylaceae d0% w4%), Physalis pubescens 2% (Solanaceae d0% w3%), Hovenia dulcis 2% (Rhamnaceae d0% w3%), Asterostigma lividum 1% (Araceae d3% w0%), Vitis sp 1% (Vitaceae d0% w2%) and Syagrus romanzoffiana 1% (Arecaceae d0% w2%)- The following were all recorded in one winter sample only Casearia decandra (Flacourtiaceae), Rubus sp (Rosaceae), Solanum maioranthum and Solanum pseudoquina (both Solanaceae). Unidentified seeds accounted for 6% (Vitaceae d8% w5%) Items of human refuse 10% (d9% w10%), were also found in samples suggesting scavenging at rubbish tips. Fruit were considered to be of particular importance for young animals and lactating females. Ceotto et al (2009) studied the diet of the species in a disturbed rural area in Sumidouro, Rio de Janeiro. As with previous studies they found no difference in diet between sexes. However, unlike in the restinga, the relative frequency of fruit was higher in humid months suggesting generalist usage of a seasonally abundant food item in this humid environment, whilst other food items remained constant throughout the year. The species was found to take less vertebrate prey than sympatric Philander frenatus, whilst consumption of fruit and invertebrates was approximately the same in both species. However D.aurita consumed a wider variety of fruit and whilst the diversity of invertebrates was similar the composition was different, with Philander consuming crustacea and mollusca, whilst D.aurita took mainly litter-dwelling arthropods. It was suggested that these dietary differences reduce competition and allow for co-existence of the two species. The dietary flexibility and ability to take advantage of seasonally-abundant foodstuffs is likely responsible for its survival capacity in diverse habitats, at least in Brazil. Astúa de Morães et al (2006) caught individuals at Rio Doce State Park, Minais Gerais, Brazil using ground Tomahawk traps baited with bacon and peanut butter. Astúa de Morães et al. (2003) experimentally tested the proportions of protein, lipid, carbohydrate and fibre in the diet of adults (n=36) and juveniles (n=18) of this species under laboratory condtions. Mean proportions per 100g dry weight of food were: protein ad. 16.28g (+/-8.75), juv. 7.32g (+/-4.63); lipid ad. 5.08g (+/-5.40), juv. 1.53g (+/-1.41); carbohydrate ad. 26.70g (+/-19.38), juv. 10.87g (+/-10.60); fibre ad. 1.94% (+/-0.43), juv. 1.77% (+/-0.41). Santori et al (2004) described and illustrated the gut morphology of this species and associated it with dietary habits, whilst Santori et al (1995) made comparisons with Philander frenatus.

PRINT 33:

Didelphis aurita

Adapted from Massoia et al (2006) and Yanosky & Villalba (2000).

Click the image to enlarge it.