Designed by Paul Smith 2006. This website is copyrighted by law.

Material contained herewith may not be used without the prior written permission of FAUNA Paraguay.

Photographs on this web-site were taken by Paul Smith, Hemme Batjes, Regis Nossent, Frank Fragano,

Alberto Esquivel, Arne Lesterhuis, José Luis Cartes, Rebecca Zarza and Hugo del Castillo and are used with their permission.

Chrotopterus auritus (W. Peters 1856) Image Gallery

TAX: Class Mammalia; Subclass Theria; Infraclass Metatheria; Order Chiroptera; Suborder Microchiroptera; Superfamily Noctilionoidea; Family Phyllostomidae; Subfamily Phyllostominae (López-Gonzalez 2005, Myers et al 2006). This species is the sole representative of the genus Chrotopterus, Peters 1865. The origin of the name Chrotopterus is Greek meaning "skin wing" presumably in reference to the wing membranes. The species name auritus is Latin meaning "long-eared". Carter & Dolan (1978) disputed the designation of Mexico as the type locality and claimed that the type specimen actually came from Santa Catarina, Brazil. However Peters (1856) clearly states that the specimen is from Mexico and Medellín (1989) claims that the type specimen is ZMB 10058 in the Zoologisches Museum der Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, which consists of a clean skull and skeleton with body parts in alcohol (Gardner 2007). Traditionally three subspecies have been recognised, that present in Paraguay is C.a.australis Thomas 1905 (Type Locality Concepción, Paraguay). Supposedly this subspecies is distinguished by its extensive woolly grey pelage which covers the wing and tail membranes reaching the elbows and knees, a small white spot on the wing tips and a woolly patch on the metacarpal of the thumb. Paraguayan specimens examined by Myers & Wetzel (1983) shared these characteristics. However given the wide geographic range of the species and the relatively small number of specimens available for comparison, many modern authors prefer to consider the species as monotypic pending a thorough revision (López-González 2005, Gardner 2007). Synonyms adapted from Medellín (1989), Gardner (2007) and López-González (2005).

Vampyrus auritus W. Peters 1856:305. Type locality "Mexico et Guyana". Restricted to Mexico by Peters (1856)

[Vampyrus (]Chrotopterus[)] auritus W. Peters 1865:505. Name combination.

Chrotopterus auritus Hensel 1872:20. First use of current name.

[Vampyrus (Chrotopterus)] auritus Trouessart 1897:153. Name combination.

ENG: Woolly False Vampire (Sazima 1978), Woolly False Vampire Bat (Medellín 1989), Peters´s Woolly False Vampire Bat (Eisenberg & Redford 1999, Nowak 1991), Peters´ False Vampire Bat (Rick 1968), Great Woolly Bat (Gardner 2007), Big-eared Wooly (sic) Bat (IUCN 2008).

ESP: Falso vampiro lanudo (Emmons 1999), Falso vampiro orejón (Redford & Eisenberg 1992, Chebez 1996), Gran murciélago carnívoro (Chebez 1996), Murciélago gigante (Chebez 1996), Murciélago orejudo (Chebez 1996), Murciélago orejudo mayor (Chebez 1996).

GUA: Mbopí-guasu (Chebez 1996).

DES: This is one of the largest bats in Paraguay with exceptionally long, round-tipped ears that are well-separated on the head. Ears hairy on the posterior part of the inner margin. Tragus small, elongated and pointed. The nose leaf is long, broad and blunt with a thick rib and well-developed lower element that borders the nostrils. Snout long and narrow. Vibrissae are scarce and warts are present at the bases. Lower lip with two thickened areas forming a V-shaped groove. Lips, nose leaf and ears pale brownish-pink in colour. Eyes rounded, black and beady. Pelage thick, woolly and greyish, being slightly shorter and paler ventrally than dorsally where it is c12mm long. Forearm heavily furred on both sides for at least two-thirds of total length. Thumb long and with strongly curved claws, it being furred for the basal half. Propatagium dark brown, well-developed and furred to almost the elbow. Terminal phalanx of the third digit whitened and surrounding membrane lightened for about 1.5cm at the tip. First phalanx of middle finger >50% of metacarpal length and subequal to the second phalanx. The uropatagium is wide, long and completely encloses the short tail, which may on occasion appear to be completely absent. Calcar slightly shorter than foot. Males have a glandular structure on the foreneck that is absent in females. (Peters 1856, Medellín 1989, Nowak 1991, Anderson 1997).

CR - Skull robust with wide rostrum. Lower mandible robust. Braincase elongate and expanded with prominent sagittal and lamboidal crests. Wide, strong zygomatic arches. Auditory bullae small. (Medellín 1989). The following measurements are based on a series of unsexed Paraguayan specimens published in López-González (2005): Greatest Skull Length 36.1mm (+/- 0.74); Condylobasal Length 31.1mm (+/- 0.68); Transverse Zygomatic Width 19.2mm (+/- 0.74); Mastoid Width 17.5mm (+/- 0.55); Interorbital Constriction 6.1mm (+/- 0.18); Width Across Upper Molars 11.9mm (+/- 0.26); Width Across Upper Canines 7.1mm (+/- 0.29). DF: I2/1 C1/1 P 2/3 M 3/3 = 32. The following measurements are based on an unsexed series of Paraguayan specimens published in López-González (2005): Upper Tooth Row 12.5mm (+/- 0.28); Lower Tooth Row 14.5mm (+/- 0.34). The presence of only a single pair of lower incisors is diagnostic when compared to species of a similar size. Canines and upper incisor well-developed. First upper premolar minute and displaced on labial side. Upper molars robust with W-shaped lophs and prominent hypocones and protocones. Lower canines protrude beyond lower incisors giving protognathous state. Only first and third lower premolar are well-developed. (Medellín 1989). CN: 2n=28. FN=52. (Medellín 1989). The X-chromosome is submetacentric and the Y-chromosome is acrocentric. The standard karyotype shows a close relationship to bats of the genera Tonatia and Lophostoma.

MMT: One of the largest Paraguayan bats. The following measurements are based on a series of unsexed Paraguayan specimens published in López-González (2005): TL 139.7mm (+/- 27.65); TA 37.3mm (+/- 17.41); FT 24.2mm (+/- 1.86); FA 80mm (+/- 3.61); EA 48.3mm (+/- 2.12); Length of Third Digit 61.3mm (+/- 1.95); WT 84.6g (+/- 7.98).

SSP: This species can be easily identified on the basis of its large size (it is one of the largest bats in Paraguay), long, woolly pelage and extremely long ears. Only Phyllostomus hastatus approaches it in size, but that species has dense, short, velvety pelage and much shorter ears (c28mm in P.hastatus compared with c48.3mm in C.auritus). Note also that this species has only a single pair of lower incisors, other Paraguayan bats of similar size and aspect have two pairs.

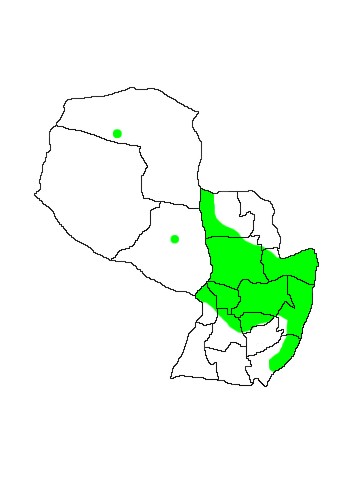

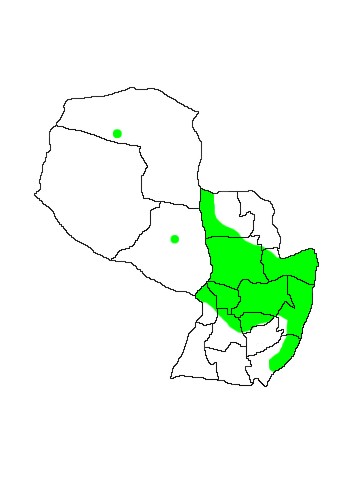

DIS: Widespread throughout the Neotropics from Chiapas, Oaxaca, Quinatana Roo, Tabasco and Yucatan in Mexico south to northern Argentina. The species is distributed predominately east of the Andes, with a circum-Amazonian range and occurs in every Neotropical country except Chile and Uruguay. The species is generally considered monotypic (López-González 2005, Gardner 2007) though three subspecies are sometimes recognised. C.a.auritus Peters 1856, is found in Central America and northwestern Colombia; C.a.guianae Thomas 1905, occurs in northern South America from eastern Colombia, Venezuela, the Guianas, south to north-eastern Peru and northern Brazil; C.a.australis Thomas 1905, is found in the remainder of the range south through much of Bolivia and Paraguay to northern Argentina and Brazil south to central Rio Grande do Sul.In Argentina it has been reported from the Provinces of Salta, Jujuy, Tucumán, Formosa, Chaco, Corrientes and Misiones (Barquez et al 1993). In Paraguay specimens are known from almost all Departamentos except Boquerón, Ñeembucú, Misiones, Amambay and Caaguazú, however the species is principally distributed in the eastern region with only a scattering of records in the Chaco, the majority close to the banks of the Rio Paraguay (López-González 2005).

HAB: Typically a species of humid forested areas, being found at low density in the Atlantic Forest of eastern Paraguay. However there is a specimen from the Dry Chaco at Cerro León, Departamento Boquerón which was taken in low thorny woodland and another from palm savanna in the Humid Chaco site of Fortín Orihuela, Departamento Presidente Hayes which suggest that the species may undertake movements and make use of seasonally-productive habitats, at least during some parts of the year (López-González 2005). The majority of specimens are collected close to water, frequently along forested streams or trails, but also in thick, secondary scrub. The species typically occurs where bat species-richness is high. (Medellín 1989).

ALI: This large bat is at least partly carnivorous taking mainly vertebrate prey supplemented with large insects. A captive specimen refused fruit that was offered but readily consumed vertebrates and was maintained on a diet of raw beef, House Sparrows Passer domesticus, bats and lab rats and mice (Peracchi & Alburquerque 1976). From their observations of this captive individual they suggested that the hunting technique may involve visual and echolocation searches from a temporary roost. Medellín (1988) noted that prey species offered to a captive individual would be followed by constant reorientation of the ears and nose leaf when it was moving, but interest would be lost when if they became quiet and would only be reignited upon the production of sound. Prey was taken only when it approached the bat and it was not actively pursued. Large prey is typically consumed close to the place of capture whereas smaller prey is carried to the roost for consumption. The process of prey consumption lasted from 1 to 20hrs in captivity (Medellín 1988, Noguiera et al 2006). A male taken in Venezuela had recently consumed a large arboreal gecko Thecadactylus rapicaudus (Tuttle 1967) an arboreal species which can reach 15cm in size and is nocturnal in behaviour. Constantine (1966) reported that a male specimen captured in Mexico and kept in captivity ate mice and other bats, and "enthusiastically grasped gloved fingers which it proceeded to chew quite effectively in the same manner (..as it despatched its prey)". Sazima (1978) found bone fragments of an anuran "probably a hylid tree-frog" in the stomach of a young male taken in Sao Paulo State, Brazil. Bird species recorded in the diet across the range include antshrikes Thamnopilus sp., ground-doves Columbina talpacoti, bush-tanagers Chlorospingus ophthalmicus, black-tyrants Knipolegus cabanisi and wood-warblers Dendroica sp. Mammal prey include mouse-opossums ex-Marmosa, shrews Sorex sp. and mice (Heteromys, Reitrhodontomys, Peromyscus, Ototylomys, Nyctomys etc). There is a single record of another species of bat being consumed, Glossophaga soricina in the wild in Brazil (Acosta y Lara 1951) , though several authors have fed small bats to captive individuals. Delpietro et al (1992) noted that individuals observed in Provincia Corrientes, Argentina showed no interest in bats captured in mist nets as prey items. Noquiera et al (2006) documented the predation of a Carollia perspicillata by a female individual in Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil - the bat having been apparently captured and half-eaten before hitting a mist net. Typically only large insects are taken such as Coleoptera (Cerambycidae, Scarabaeidae) and Lepidoptera (Sphingidae). Prey of captive individuals is consumed from the head down, victims being surrounded by the wing membranes and held firm by the thumbs. Bats and mice are killed by bites to the throat or nape and birds are dispatched with bites to the top of the head. Hard bony items such as beaks, rostra, limbs and long feathers are discarded as are occasionally the viscera and though faeces contain mainly hair (typically <5mm long), long guard hairs are apparently not consumed. During consumption prey may be held in the mouth or supported against the inner surface of one folded wing. (Medellín 1988). There has been some suggestion that there is resource partitioning with the largely sympatric, predatory Vampyressa spectrum with that species concentrating largely on non-passerine birds and bats, and this species preferring passerines and rodents. Prey items range in mass from 10-35g, with a maximum of 70g. Mammalian prey in Chiapas, Mexico accounted for 79% of the vertebrate prey and 68% of the total prey items taken. In total vertebrates accounted for 86% of the prey items. (Medellín 1988, Medellín 1989). Ruschi (1953) provided details of haematophagous feeding in this species as well as a suggestion of frugivory, though there have been no further reports of such behaviours and they was placed in doubt by later authors. The foraging area of a young female in Costa Rica was shown to cover an area of 4ha adjacent to its roost (A.Brooke in litt in Medellín 1989). Delpietro et al (1992) noted that of three individuals captured (two males and a lactating female), only the female had fed and suggested that a group living system in which preference is given to reproductive females at feeding time may exist as in the Common Vampire Bat Desmodus rotundus.

REP: As with other members of the family they give birth to a single young. Data on breeding suggests that the cycle is monestrous with dates varying by latitude. Pregnant females have been taken in Argentina in July and Mexico in April. Delpietro et al (1992) captured a lactating female on 21 December 1984 in Provincia Corrientes, Argentina. Barquez (1986) noted pregnant females in October and males showing signs of reproductive activity in November in Provincia Salta, Argentina. Males with scrotal testes have been found in Argentina during July. A female captured in Sao Paulo state and kept in isolation gave birth after 99 days, and in the same region female reproductive activity appeared to be confined to the second half of the year (Taddei 1976).

BEH: Activity Levels Flight is slow, making them difficult to catch in mist nets as they are able to take necessary evasive action, however they have been caught in dense thickets at a height of 1 to 2m (Redford & Eisenberg 1992). Wing-loading value is high among the Phyllostomids at 18.81 N/m2 and is second only to Phyllostomus in the family. The basal metabolic rate is high and body temperatures do not vary widely when subjected to varying environmental temperatures. Delpietro et al (1992) observed a group of four individuals flying together on several occasions along a forest trail at a height of c3m in Provinica Corrientes, Argentina but they were not seen to utilise nearby open habitat. One of these individuals when captured in a mist net began to vocalise loudly attracting the other members of the group and resulting in the capture of a second individual. The original bat captured continued to vocalise even when removed from the net and placed in a bag which were then left close to the net resulting in the capture of a third individual, the remaining bat having departed. On another occasion four of five bats in a group were captured under similar circumstances, consisting of three adult males and a lactating adult female. They concluded that a dominance hierarchy may operate within groups and that groups may exist to improve hunting success. Roosts Roosts are located in crevices or caves, including tree holes (Medellín 1988), ruins of buildings (Rick 1968), hollow termite mounds and mines and no correlation exists between preferential roost site and habitat type (Medellín 1989). Typically roosts are monospecific, but occasionally are shared with other species including Desmodus rotundus (Venezuela, Brazil, Argentina, Costa Rica), Glossophaga soricina (Brazil), Tadarida brasiliensis (Mexico), Phyllostomus hastatus (Venezuela) and Peropteryx macrotis (Venezuela). Colonies may contain between 1 and 7 individuals (Medellín 1988), with 3 to 5 the typical colony size (Sazima 1978) and roost site may be changed frequently (Medellín 1988). Relative humidity within Brazilian roosts was found to be between 77-93% with a temperatue of 14-22oC (McNab 1969). Enemies No natural enemies of this species are known. Parasites Parasites include two Streblid flies Strebla wiedemanni and Trichobius dugesioides; a red mite Hooperella vesperuginis; a Nycteribiid fly Basilia ortizi and a tick Ornithodoros brodyi. The Nycteribiid fly Basilia hughscotti and the Diplostomid trematode Neodiplostomum vaucheri are known only from this species. (Medellín 1989). Parasites Presley (2005) found high parasite loads on this species in Paraguay with 151 parasites on 3 specimens of this bat. High abundances may account for how a streblid (Strebla chrotopteri) and trombiculid (Trombicula sp.) that infest only this relatively uncommon host species persist through ecological time. Such high infestation rates reduce the chance of local extinction of a parasite, which may be an important if the only host is a rare, long-lived species. Longevity This species has been maintained in captivity for over a year (Peracchi & Alburquerque 1976). A male captured by Delpietro et al (1992) was at least 5 years old, having been marked as an adult in 1984 and recaptured in 1988.

VOC: As with other foliage-gleaning bats the echolocation is of short duration (<2msec), low amplitude and high frequency with multiple harmonics (Medellín 1989).

HUM: Human impact likely negligible.

CON: Globally considered to be of Least Concern by the IUCN, click here to see the latest assessment of the species. Considered potentially vulnerable in Paraguay by López-Gonzalez (2005) though no further information was provided and the species occurs in several protected areas. As a large, predacious species this bat occupies a place near the top of the food chain and occurs at naturally low density. The alarming destruction of the Atlantic Forest habitat that this species utilises has undoubtedly had serious effects on the population of this species in Paraguay and its low reproductive rate hampers the species ability to recover rapidly from population declines. Medellín (1989) states that the species probably depends on primary forest with sufficient roost sites.

Citable Reference: Smith P (2008) FAUNA Paraguay Online Handbook of Paraguayan Fauna Mammal Species Account 24 Chrotopterus auritus.

Last Updated: 27 December 2008.

References:

Acosta y Lara F 1951 - Notas Ecológicas sobre algunos Quirópteros de Brasil - Comm. Zool. Museo de Montevideo 3: p1-2.

Anderson S 1997 - Mammals of Bolivia: Taxonomy and Distirbution - Bulletin AMNH 231.

Barquez RM 1986 - Los Murciélagos de Argentina - PhD Thesis Universidad de Turcumán, Argentina.

Barquez RM, Giannini NP, Mares MA 1993 - Guide to the Bats of Argentina - Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, Norman, Oklahoma.

Carter DC, Dolan PG 1978 - Catalogue of the Type Specimens of Neotropical Bats in Selected European Museums - Special Publications of the Museum of Texas Tech University 15.

Constantine DG 1966 - New Bat Locality Records from Oaxaca, Arizona and Colorado - Journal of Mammalogy 47: p125-126.

del Pietro HA, Contreras JR, Konolaisen JF 1992 - Algunas Observaciones acerca del Murcielago Carnivoro Chrotopterus auritus en el Noreste Argentino - Notulas Faunisticas 26: p1-7.

Eisenberg JF, Redford KH 1999 - Mammals of the Neotropics: Volume 3 The Central Neotropics - University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Emmons LH 1999 - Mamíferos de los Bosques Húmedos de América Tropical - Editorial FAN, Santa Cruz.

Gardner AL 2007 - Mammals of South America Vol 1: Marsupials, Xenarthrans, Bats and Shrews - University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Hensel R 1872 - Beiträge zue Kenntniss der Säugethiere Süd-Brasiliens - Abhandl. König. Akad. Wiss. Berlin 1872: p1-130.

López-Gonzalez C 2005 - Murciélagos del Paraguay - Biosfera Numero 9.

McNab BK 1969 - The Economics of Temperature Regulation in Neotropical Bats - Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology 31: p227-268.

Medellín RA 1988 - Prey Items of Chrotopterus auritus with Notes on Feeding Behaviour - Journal of Mammalogy 69: p841-844.

Medellín RA 1989 - Chrotopterus auritus - Mammalian Species 343.

Myers P, Espinosa R, Parr CS, Jones T, Hammond GS, Dewey A 2006 - The Animal Diversity Web (online). Accessed December 2007.

Myers P, Wetzel RM 1983 - Systematics and Zoogeography of the Bats of the Chaco Boreal - Miscellaneous Publications of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan 165.

Nogueira MR, Monteiro LR, Peracchi AL 2006 - New Evidence of Bat Predation by the Woolly False Vampire Bat Chrotopterus auritus - Chiroptera Neotropical 12: p286-288.

Novak RM 1991 - Walker´s Mammals of the World 5th Ed Volume 1 - Johns Hopkins, Baltimore.

Peracchi AL, Albuquerque ST 1976 - Sobre os Habitos Alimentares de Chrotopterus auritus australis Thomas, 1905 (Mammalia, Chiroptera, Phyllostomidae) - Revista Brasileira de Biologia 36: p179-184.

Peters WCH 1856 - Systematische Stellung der Gattung Mormoops Leach und über die Classification der Phyllostomata Savie über eine neu Art der Gattung Vampyrus von Welcher Hier ein Kurzer Bericht Gegeben Wird - Monatsberichte der Königlichen Preussichen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin 1860: p747-754.

Peters WCH 1865 - Über die zu den Vampyri gehörigen Fledethiere und über die Natürliche Stellung der Gattung Antrozus - Monatsberichte der Königlichen Preussichen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin 1865: p503-524.

Presley SJ 2005 - Ectoparasitic assemblages of Paraguayan bats: ecological and evolutionary perspectives - Texas Tech University PhD Dissertation.

Rick AM 1968 - Notes on Bats from Tikal, Guatemala - Journal of Mammalogy 49: p516-520.

Ruschi A 1953 - Algumas observacoes sobre alimentacao de quiropteros Phyllostomus hastatus (Pallas), Molossus rufus E.Geoffroy, Chrotopterus auritus australis (Thomas) e Noctilio leporinus leporinus (Linnaeus) - Boletim Museo Biologia Mello Leitao Biol. 14: p1-5.

Sazima I 1978 - Vertebrates as Food Items of the Woolly False Vampire Chrotopterus auritus - Journal of Mammalogy 59: p617-618.

Taddei VA 1976 - The Reproduction of some Phyllostomidae (Chiroptera) from the Northwestern Region of the State of Sao Paulo - Boletim Zool. Univ. Sao Paulo 1: p313-330.

Thomas O 1905 - New Neotropical Chrotopterus, Sciurus, Neacomys, Coendu, Proechymys and Marmosa - Annals and Magazine of Natural History Series 7 16: p308-314.

Trouessart EL 1897 - Catalogus mammalium tam viventium quan fossilium. Fasciculus I. Primates, Prosimiae, Chiroptera, Insectivora - R. Friedländer and Sohn, Berolini.

Tuttle MD 1967 - Predation by Chrotopterus auritus on Geckos - Journal of Mammalogy 48: p319.

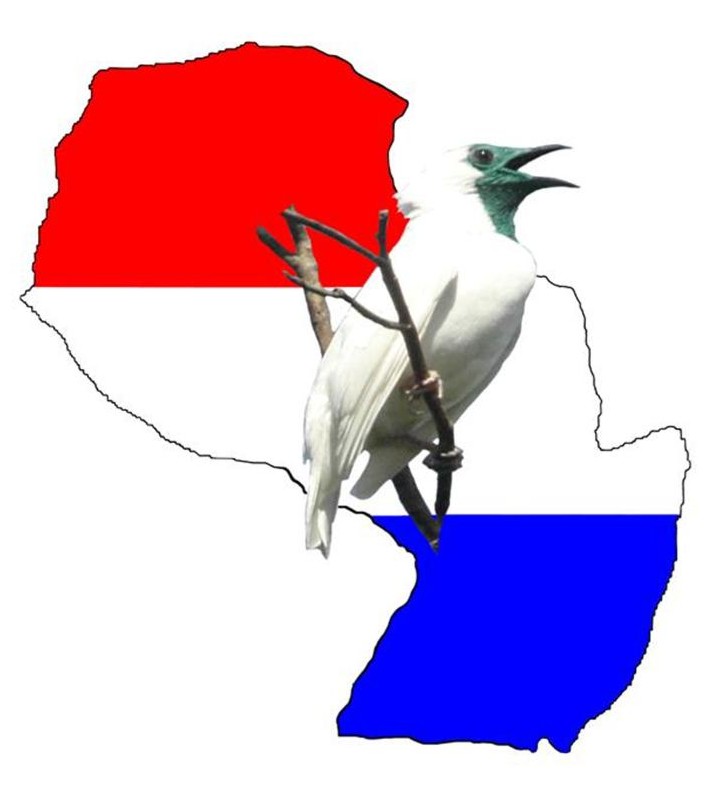

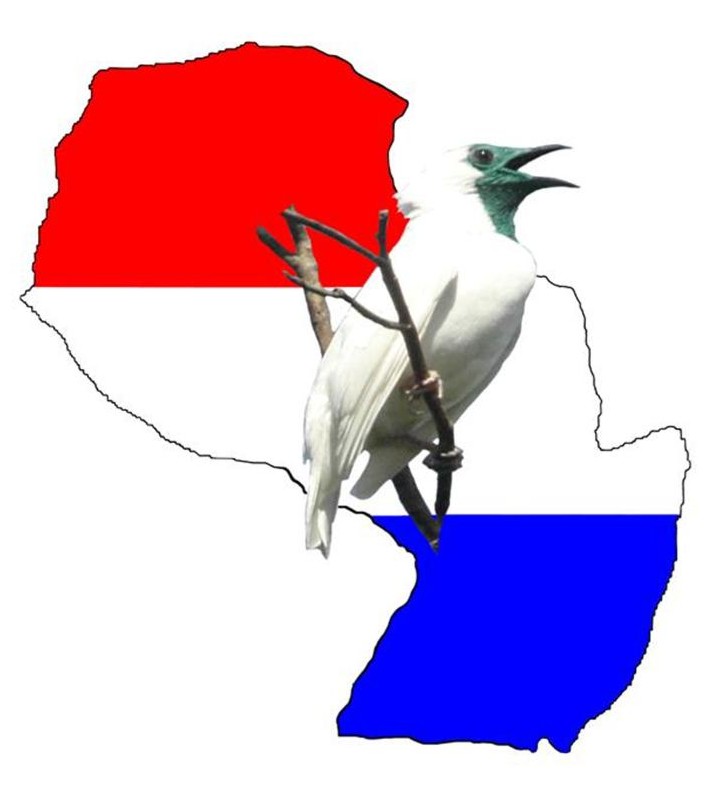

MAP 24:

Chrotopterus auritus