Designed by Paul Smith 2006. This website is copyrighted by law.

Material contained herewith may not be used without the prior written permission of FAUNA Paraguay.

Photographs on this web-site were taken by Paul Smith, Hemme Batjes, Regis Nossent, Frank Fragano,

Alberto Esquivel, Arne Lesterhuis, José Luis Cartes, Rebecca Zarza and Hugo del Castillo and are used with their permission.

Noctilio albiventris Desmarest 1818 Image Gallery

TAX: Class Mammalia; Subclass Theria; Infraclass Metatheria; Order Chiroptera; Suborder Microchiroptera; Superfamily Noctilionoidea; Family Noctilionidae (Hoofer et al 2003, López-Gonzalez 2005, Myers et al 2006). The genus Noctilio, Linnaeus 1766, is the only genus in the family and contains two species, both of which are present in Paraguay. The origin of the name Noctilio is uncertain but is probably derived from the Latin “noctis” meaning “night” or perhaps from the French Noctilion meaning “bat” from the same root. The species name albiventris is Greek meaning “white-bellied”. This species was for a long time referred to by the name Noctilio labialis until it was demonstrated that that name referred to a specimen of N.leporinus (Hershkovtiz 1975, Davis 1976) and prior to that was placed in the genus Dirias (Thomas1920). The name Noctilio ruber (Rengger 1830) based on Azara´s "chauve-souris onzieme," from Paraguay was believed to refer to this species by Hershkovitz (1975) but according to Davis (1976) the name clearly refers to a Myotis, and probably Myotis ruber. No type specimen apparently exists and Cabrera (1958) fixed the type locality as Rio São Francisco, Bahía, Brazil as the first published locality for the species by Spix (1823). Noctilio albiventer Desmarest (1820) is based on the "Noctilion à ventre blanc" of E. Geoffroy St.Hilaire and Pennant´s (1971) Peruvian Bat Var. ß". It is not possible to determine whether this name change from Desmarest´s own work (1818) is due to an unjustified emendation of the original name or simply a spelling error. There are four recognised subspecies, that present in Paraguay is N.c.cabrerai Davis 1976 (Type Locality Fuerte Olimpo, Departamento Alto Paraguay, Paraguay). Supposedly this subspecies is distinguished by paler colouration and smaller size when compared to other populations, but there is convincing circumstantial evidence to suggest that size change across the species range is clinal with populations at the northern and southern extremes of the range averaging larger and there is considerable variation in colour between individuals at any one given site. Myers & Wetzel (1983) considered that the size differences did not warrant subspecific separation, but this was refuted by Taddei et al (1986) who found considerable differences in size between a population in southeastern Brazil and those in Paraguay which they believed sufficient to confirm its subspecific separation. Gardner synonymsied N.a.affinis WB Davis 1976, with N.a.albiventris. López-González (2005) stated that a revision of the geographic variation of the species was necessary before conclusions could be drawn and elected not to assign the Paraguayan populations to subspecies pending such a study. Synonyms adapted from Hood & Pitocchelli (1983), López-Gonzalez (2005) and Gardner (2007):

Noctilio albiventris Desmarest 1818:15. Type locality "L´Amerique Meridionale". Restricted to Rio São Francisco, Bahía, Brazil by Cabrera (1958) on the basis of Spix (1823).

Noctilio albiventer Desmarest 1820:118. Unjustified emendation or incorrect spelling.

Noctilio albiventer Spix 1823:58. Type locality "Fluviem St Francisi" (=Rio São Francisco, Bahía, Brazil).

Noctilio affinis d’Orbigny 1837: Plate 10, fig 1. Type locality "Concepción", Beni, Bolivia, based on d’Orbigny & Gervais (1847).

Dirias albiventer Miller 1906:84. Name combination.

Noctilio zaparo Cabrera 1907:57. Type locality "Ahuano on Rio Nap" Napo, Ecuador.

Noctilio minor Osgood 1910:30. Type locality "Encontrados, Zulia, Venezuela".

Noctilio albiventer minor Osgood 1912:62. Name combination.

Dirias zaparo JA Allen 1916:225. Name combination.

Dirias irex O. Thomas 1920:273. Type locality "Santa Julia, Rio Iriri, Rio Xingú" Pará, Brazil.

Dirias albiventer minor Goldman 1920:117. Name combination.

Dirias albiventer albiventer Cabrera 1930:426. Name combination.

Dirias minor Goodwin 1942:211. Name combination.

Noctilio (Dirias) albiventer Sanborn 1949:279. Name combination.

Noctilio labialis Hershkovitz 1949:434. Not Noctilio labialis Kerr (1792).

Noctilio labialis albiventer Hershkovitz 1949:434. Name combination.

Noctilio labialis labialis Hershkovitz 1949:434. Name combination.

Noctilio labialis minor Hershkovitz 1949:433. Name combination.

Noctilio labialis albiventris Cabrera 1958:55. Name combination.

Noctilio labialis zaparo Cabrera 1958:56. Name combination.

Noctilio albiventris albiventris Hershkovitz 1975:244. First use of current subspecific name.

Noctilio albiventris minor Hershkovitz 1975:244. First use of current subspecific name.

Noctilio albiventris ruber Hershkovitz 1975:244. Name combination. Not Vespertilio ruber Rengger (1830).

Noctilio albiventris zaparo Hershkovitz 1975:244. Name combination.

Noctilio albiventris affinis WB Davis 1976:687. First use of current subspecific name.

Noctilio albiventris cabrerai WB Davis 1976:701. Type locality "Fuerte Olimpo, Depto. de Olimpo (=Alto Paraguay), Paraguay".

ENG: Lesser Bulldog Bat (Hood & Pitocchelli 1983, Barquez, Giannini & Mares 1993, Eisenberg 1989), Southern Bulldog Bat (Redford & Eisenberg 1992), Little Bulldog Bat (Rasweiler 1977), Lesser Noctilio (Davis 1976).

ESP: Murciélago pescador chico (Barquez, Giannini & Mares 1993), Murciélago buldog menor (Emmons 1999), Pescador menor (Redford & Eisenberg 1992).

GUA: Mbopi pyta (Emmons 1999).

DES: This is a large bat, with a protruding nose lacking a nose leaf, and a strongly swollen and cleft forelip which exposes the large canines and pointed incisors. The chin is prominent and has conspicuous lateral ridges, and there are internal cheek pouches. The forward-leaning ears are separate, long, narrow and pointed with a lobed tragus. Ears are naked and brownish and furred only at the base. The tail is more than half the femoral length and extends to about half the uropatagial length, the tip of the tail pointing free on the dorsal surface. Uropatagium extends beyond the large and robust feet (though less so than the Greater Bulldog Bat) and there is a well-developed bony calcaneous. Pelage short. Paraguayan specimens are typically brownish dorsally, with a small proportion of the population more rufous-orange in colour. Typically there is little difference in colour between the dorsum and the venter. A thin longitudinal line along the dorsal surface, from the interscapular region to the rump, is usually paler than the rest of the pelage, but is barely discernible in some specimens. Wings long, narrow and pointed. Wing and tail membranes are brown and semitranslucent. Flanks naked. Live specimens have a strong musky odour. CR - Skull robust with high, deep braincase, flared mastoids and prominent sagittal crest (more so in males). Lacks well-developed post-orbital processes. Palate complete and closed anteriorly, appearing concave when viewed laterally but flat longitudinally. Premaxillaries fused to maxillaries and nasal and palatal branches fused together. Rostrum arched, about half the length of brain case and nares tubular and forward-opening. Maxillary toothrows approximately parallel. Auditory bullae small and covering half of the cochlea (Hood & Pitocchelli 1983). The following measurements are based on a series of Paraguayan specimens published in López-González (2005) for northern (1), central (2) and southern (1) localities respectively in Paraguay: 1 Estancia Doña Julia, Departamento Alto Paraguay 20º10.98´S, 58º09,42´W: Greatest Skull Length male 19.9mm (+/- 0.6) female 19.7mm (+/- 0.13); Condylobasal Length male 18.8mm (+/- 0.3) female 18.5mm (+/- 0.66); Transverse Zygomatic Width male 15.6mm (+/- 0.27) female 15.4mm (+/- 0.02); Mastoid Width male 15.6mm (+/- 1.03) female 14.6mm (+/- 1.14); Interorbital Constriction male 5.9mm (+/- 0.2) female 5.8mm (+/- 0.27); Width Across Upper Molars male 9.8mm (+/- 0.24) female 9.8mm (+/- 0.24); Width Across Upper Canines male 7mm (+/- 0.21) female 6.6mm (+/- 0.34). 2 17km east of Luque, Departamento Central: Greatest Skull Length male 20.7mm (+/- 0.77) female 19.4mm (+/- 0.45); Condylobasal Length male 19.6mm (+/- 0.38) female 18.6mm (+/- 0.52); Transverse Zygomatic Width male 15.7mm (+/- 1.43) female 15.1mm (+/- 0.33); Mastoid Width male 15.7mm (+/- 1.43) female 14.3mm (+/- 0.36); Interorbital Constriction male 6.1mm (+/- 0.1) female 5.8mm (+/- 0.19); Width Across Upper Molars male 10.1mm (+/- 0.29) female 9.6mm (+/- 0.26); Width Across Upper Canines male 7.3mm (+/- 0.35) female 6.6mm (+/- 0.22). 3 Departamento Misiones: Greatest Skull Length male 21.4mm (+/- 0.86) female 19.7mm (+/- 0.41); Condylobasal Length male 20.2mm (+/- 0.38) female 19.1mm (+/- 0.28); Transverse Zygomatic Width male 16.5mm (+/- 0.32) female 15.4mm (+/- 0.45); Mastoid Width male 16.6mm (+/- 1.33) female 14.8mm (+/- 0.3); Interorbital Constriction male 6.2mm (+/- 0.23) female 6.1mm (+/- 0.12); Width Across Upper Molars male 10.2mm (+/- 0.16) female 9.9mm (+/- 0.24); Width Across Upper Canines male 7.4mm (+/- 0.23) female 6.7mm (+/- 0.17). DF: I2/1 C1/1 P 1/2 M 3/3 = 28. Upper incisors sharply-pointed and crowded around midline between canines. Innrmost pair of incisors twice as high as they are long and with shafts that curve outwards distally. Outer pair single-cusped, smaller and located slightly behind inner pair. Lower incisors equal and also crowded at the midline, with crowns longer than they are high and upper surface concave but not bilobed. Upper canines with distinct oblique cingulum, no secondary cusps and slightly concave with median ridge on inner surface. Lower canines with slight twist in the shaft near the middle. Upper premolar twice as broad as it is long and prominently cusped. Upper M1 and M2 are almost equal without posterior emargination and lacking any clear gap between them. Crown area of M3 about half that of M2 but prominently cusped. (Hood & Pitocchelli 1983). The following measurements are based on a series of Paraguayan specimens published in López-González (2005) for northern (1), central (2) and southern (1) localities respectively in Paraguay: 1 Estancia Doña Julia, Departamento Alto Paraguay 20º10.98´S, 58º09,42´W: Upper Tooth Row male 7.6mm (+/- 0.21) female 7.4mm (+/- 0.26); Lower Tooth Row male 8.2mm (+/- 0.22) female 7.9mm (+/- 0.32). 2 17km east of Luque, Departamento Central: Upper Tooth Row male 7.3mm (+/- 0.35) female 7.6mm (+/- 0.23); Lower Tooth Row male 8.6mm (+/- 0.25) female 8.1mm (+/- 0.2). 3 Departamento Misiones: Upper Tooth Row male 8mm (+/- 0.1) female 7.6mm (+/- 0.2); Lower Tooth Row male 8.7mm (+/- 0.17) female 8.2mm (+/- 0.16). CN: 2n=34 FN= Originally published as 58 and later revised to 62. (Eisenberg & Redford 1999). X chromosome is a medium-sized metacentric and Y a small acrocentric chromosome (Hood & Pitocchelli 1983).

MMT: A large bat though the smaller member of its family. There is marked sexual dimorphism in size and in the development of the sagittal crest, both of which are larger in males than in females. The following measurements are based on a series of Paraguayan specimens published in López-González (2005) for northern (1), central (2) and southern (1) localities respectively in Paraguay: 1 Estancia Doña Julia, Departamento Alto Paraguay 20º10.98´S, 58º09,42´W TL male 99.2 (+/- 4.80), female 93.7mm (+/- 4.62); TA male 20.2mm (+/- 3.80), female 17.1mm (+/- 0.73); FT male 17.2mm (+/- 1.3), female 16.3mm (+/- 0.58); FA male 60.6mm (+/- 1.86), female 59.3mm (+/- 0); EA male 23.8mm (+/- 0.99), female 23.7mm (+/- 2.08); Length of Third Digit male 54.6mm (+/- 0.86), female 53.4mm (+/- 0) WT male 30.7g (+/- 4.22), female 26.2g (+/- 3.09). 2 17km east of Luque, Departamento Central TL male 99.2mm (+/- 2.39), female 92.8mm (+/- 4.09); TA male 18.2mm (+/- 0.45), female 17.4mm (+/- 1.142.1); FT male 17.4mm (+/- 1.14), female 16.8mm (+/- 0.84); FA male 63.9mm (+/- 1.44), female 62.1mm (+/- 1.2); EA male 26.6mm (+/- 1.14), female 24.8mm (+/- 1.1); Length of Third Digit male 56.4mm (+/- 1.51), female 55.4mm (+/- 1.36) WT male 36g (+/- 4.3), female 31.6g (+/- 2.19). 3 Departamento Misiones TL male 97.9mm (+/- 6.39), female 104.1mm (+/- 6.01); TA male 20.3mm (+/- 4.40), female 20.3mm (+/- 2.12); FT male 18.5mm (+/- 2), female 17.5mm (+/- 1.2); FA male 66mm (+/- 0), female 63.6mm (+/- 0); EA male 22.3mm (+/- 1.49), female 22.1mm (+/- 1.07); Length of Third Digit male 60.7mm (+/- 0), female 58.1mm (+/- 0); WT male 43.2g (+/- 5.73), female 33.5g (+/- 2.82).

SSP: Bulldog bats can be immediately recognised on account of their large size, pointed ears, massive feet and "hare-lip". The two component species however are extremely similar to each other and can be distinguished with certainty only on the basis of size and body measurements. This is the smaller of the two species with forearm length <70mm, hindfoot length <27mm, and the combined length of the tibia and hindfoot is less than 70% of the forearm length. The confusion species Noctilio leporinus has a forearm length >80mm, hindfoot length>28mm and the combined length of the tibia and hindfoot is greater than 80% of the forearm length. Hood & Pitocchelli (1983) further state that this species generally has a wingspan c400mm and weight c40g compared to c500mm and c50g in leporinus. When comparing skulls the condylobasal length is <21mm in this species and >21mm in leporinus. Though there may be some overlap between the largest albiventris and smallest leporinus in other skull measurements, Hood & Pitocchelli (1983) note that the length of the maxillary toothrow is rarely more than 8mm in albiventris and rarely less than 9mm in leporinus. Upper M1 and M2 of leporinus are clearly separated unlike those of this species.

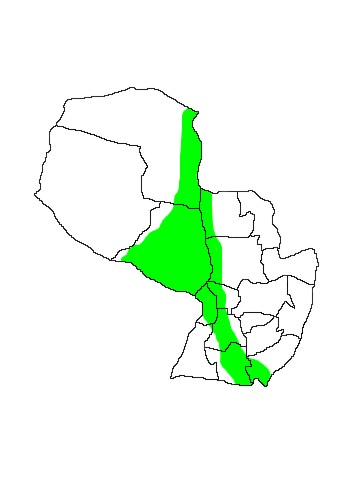

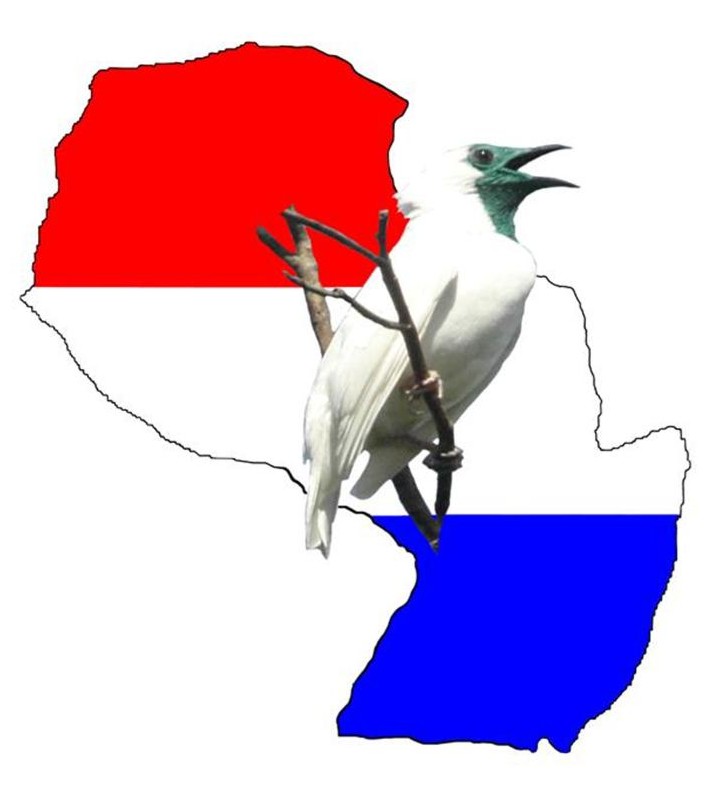

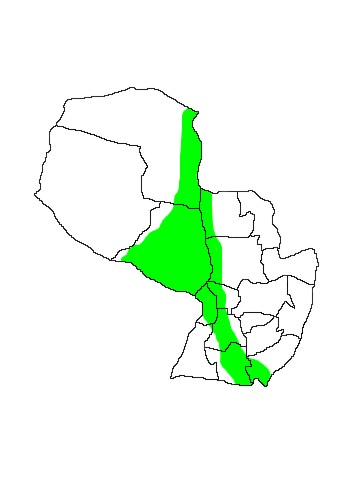

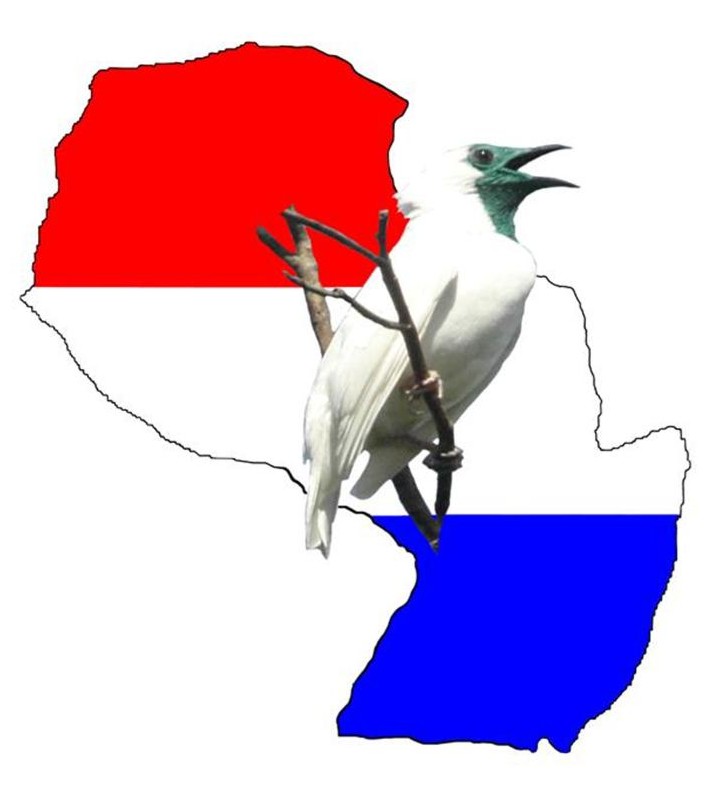

DIS: The species has a wide but discontinuous range from Guatemala and Honduras to northern Argentina and western Uruguay. Its range along the Pacific coast of Central America is patchy and it is absent from large areas of South America, including the Cerrado belt of Brazil and much of Colombia, Ecuador and Peru west of the Andes. Davis (1976) attributed the populations to four subspecies: N.a.minor Osgood 1910, occurring in Central America and northern Colombia and Venezuela; N.a.albiventris Desmarest 1818, along the eastern Amazon watershed and coast of Brazil, extending north into southeastern Venezuela and southwestern Guyana; N.a.affinis WB Davis 1976, with an unusual range in central and northern Bolivia, eastern Peru, Ecuador and Colombia, the western Amazon of Brazil, a thin finger through central Venezuela to the Caribbean coast where it extends east coastally through the Guianas to extreme northern Brazil; N.a.cabrerai WB Davis 1976, Paraguay, southern Bolviva, southern Brazil, northern Argentina and western Uruguay; however see the taxonomic section for a discussion of the validity of these subspecies. In Paraguay this species seems to be distributed along the Rios Paraguay and Paraná and their tributaries, at least as far east as Departamento Itapúa, and inland in seasonally-flooded areas of Departamento Presidente Hayes in the Humid Chaco. Noctilio bats seen foraging along the Rio Paraná in Encarnación presumably belong to this species, representing an eastward expansion from the published Paraguayan range - though the specific identity of these individuals remains to be confirmed.

HAB: Associated with larger freshwater bodies, stagnant or with a slow current, including along the Rios Paraguay and Paraná and its major tributaries. In the Humid Chaco it exploits periods of seasonal flooding, expanding into the palm savanna, but disappears from the same regions in times of drought. It seems that presence of suitable water courses is the limiting factor on its distribution and it even occurs in areas of human habitation where such conditions are met. However Myers & Wetzel (1983) note that distribution is patchy in the Chaco region and semi-isolated populations may be composed of very few individuals.

ALI: Insectivorous. Typically foraging occurs over standing or slow-moving water, often in large groups. Bats fitted with radiotransmitters in Costa Rica showed little consistency in their use of foraging areas (Fenton et al 1993). Insects may be taken aerially or from the water surface using the enlarged hind feet to grasp the insect. Echolocation is used when taking insects from the water (Nowak 1991). Individuals which approach the water mouth first are apparently drinking and not hunting. Attempts to make the species capture fish under experimental conditions have largely failed, even in some cases leading to the point of starvation, though captive individuals did eat dead fish that they were presented with (Bloedel 1955) and fish parts and scales were found in stomach contents from Costa Rica by Howell & Burch (1974). In a fecal analysis of individuals from Costa Rica and Panama Whitaker & Findley (1980) found only insects with Coleoptera (Dytiscidae and Carabidae), Hemiptera (Lygaeidae), “Homoptera” (Cercopidae), Lepidoptera and Diptera identified. The large water beetle family Dytiscidae predominated with 22.5% by volume confirming aquatic feeding. Similar results of Coleoptera, Lepidoptera, Hemiptera, Hymenoptera, Diptera, Orthoptera and “Homoptera” were reported for Costa Rica by Hooper & Brown (1968), Nicaragua by Jones et al (1971) and Colombia by Tamsitt & Valdivieso (1963). Hooper & Brown (1968) stated that the identifiable insects in stomach remains ranged from 4 to 20mm in length and all were capable of flight. Schnitzler et al (1994) note that small insects stranded in water and fluttering on the water surface were enough to initiate a capture response from this species but were ignored by the larger Greater Bulldog Bat. Other items recorded in the diet by Howell & Burch (1974) include pollen from Ceiba trees (Bombacaceae) as well as an observation record of an individual feeding at a Brosimum tree (Moraceae). Dobson (1878) reported seeds of genus Morus in the stomachs of several individuals. Food is chewed twice as in the Greater Bulldog Bat, a process that has been likened to "ruminating" (Goodwin 1928). During the first bout of chewing the prey is chewed rapidly and stored in cheek pouches until it has been completely consumed, it is then everted into the mouth for a second bout of chewing prior to swallowing (Bloedel 1955).

REP: Seasonal with a single short breeding season annually, probably influenced by the period of greatest insect abundance. Hooper & Brown (1968) concluded that this species breeds later in the year than the Greater Bulldog Bat in Costa Rica. Rasweiler (1977) confirmed highly synchronous breeding in individuals from Colombia with fertilisation and early embryonic development in late February and March. Ova are fertilised in the oviduct where they develop to an advances state compared with other Microchiroptera. Litter size is one pup, with a single case of twins in 72 litters reported by Rasweiler (1977). Newborns are altrical lacking fur and with eyes closed, they have large feet of similar size to those of adults, and though they are capable of crawling from birth, they grow slowly. The period of parental care of Noctilio is longer than any other bat studied except for the Vampire Bat Desmodus. Young do not fly until they are 35-44 days old, flying first with the mother and do not fly confidently until two weeks after taking to the air. Brown et al (1983) observed young bats leaving the roost for the first time to lack agility and several were seen to strike concrete posts during their early flights. They are not weaned until 75-90 days (mean=80.5) but solid food is consumed for the first time at 45 days when they take premasticated food from the cheek pouches of the female. Colour-marking of bats in a captive colony revealed that females attend only their own young which they recognise by virtue of their "isolation call" (see vocalisations section). Under experimental conditions the correct mother retrieved the correct juvenile on 65.6% of occasions - this consisting of allowing the juvenile to attach to the nipple and returning to the cluster. On the other occasions when other individuals responded to the call of another juvenile, there was no retrieval of the young and the bat flew away again apparently recognising its mistake. Distinct differences in the responses of the mothers was noted, with some mothers responding immediately on hearing the isolation call of their offspring, others showing little or no interest and some individuals reacting quickly to all isolation calls irrespective of whether it came from their own offspring or not. By 3 weeks of age the young are less inclined to utter isolation calls and mothers are as a result less responsive and by 4 weeks they actively seek out their mothers amongst the roosting groups of adults. (Brown et al 1983, Eisenberg & Redford 1999).

BEH: Activity Levels Typically there appear to be two peaks of activity per night, with an early feeding phase at dusk followed by a second feeding phase shortly after midnight (Eisenberg & Redford 1999) differing from the Greater Bulldog Bat. Hooper & Brown (1968) suggested that this difference in activity period contributes to differences in diet and reproduction and facilitates the sympatry of the two species. Fenton et al (1993) however radiotracked bats in Costa Rica and found that in the majority of cases a single flight was made by any one individual and up to four nightly flights were occasionally performed, with the number undertaken by any one individual varying nightly. Brown et al (1983) observed the majority of the bats leave roosts in Panama at dusk, but that individuals would return to the roost throughout the night. Roosts Myers & Wetzel (1983) report that in the Chaco the species uses hollowed out trunks of Quebracho Schinopsis sp trees as roosting places. Two such roosts were found, one with an exit c1m from the ground where the trunk was c30cm thick, the other in a horizontal branch c20cm in diameter and 6m from the ground. In the Bahía Negra area, Departamento Alto Paraguay individuals have been collected roosting in man-made structures from the buildings and installations associated with the Naval Base. Roosts typically have a strong musky odour characteristic of the species (Nowak 1991). Considerable energetic savings are made by forming monospecific roosts and roost selection and group interaction are both important aspects of the natural history of the species. Though individual bats may occasionally use other roosts they are typically faithful to a main roost, and during a study in Costa Rica seven radiotracked bats returned to the main roost on 51 of the 55 days they were tracked. The bats emerged from the roost c30 minutes after sunset. Time away from the roost is almost entirely dedicated to foraging activity and the species averaged 117.6min/night (+/-81.2) away from the roost during the same study. (Fenton et al 1993). The species has been maintained in captivity and proved to be a good study subject. Parasites Mites (Acari): Parakosa tadarida, P.maxima in Nicaragua. Mitonyssus sp. in Venezuela, Surinam and Bolivia. Mitonyssus noctilio was to be considered restricted to this species by Yunker & Radovsky (1980). Tick (Argasidae): Ornithodoros hasei. Bat Flies (Streblidae): Paradyschiria parvula, P.parvuloides, Noctilionstrebla aitkeni, N.maai. The latter genus is found only on bats of this family (Wenzel et al 1966). Presley (2005) found 1460 parasites on 68 specimens of this bat in Paraguay, including two streblids (Noctiliostrebla maai and Paradyschiria parvula), a chirodiscid (Lawrenceocarpus sp.), and an argasid (Ornithodoros hasei). Both streblids were monoxenous.

VOC: Echolocation begins with uniform cries of 70kHz which modulate down to 40kHz after several milliseconds. Repetition rates as high as 200s have been recorded when pursuing food. (Hood & Pitocchelli 1983). Brown et al (1983) studied the echolocation behaviour of this species in wild and captive scenarios in Panama. They noted that prey was captured using a combination of constant and frequency-modulated pulses and while flying over water searching for prey that they frequently alternate constant frequency narrow band frequency modulated signals with constant frequency wide band frequency modulated signals. Upon approaching an object an almost pure frequency-modulated pulse is given. The constant frequency component was between 65-75kHz, differing from that of the Greater Bulldog Bat (55-65kHz) and meaning that the two species can be distinguished in the field through their sonar signals. Juveniles give long frequency-modulated "isolation calls" and shorter mixed constant/frequency-modulated pulses (duration c 10ms) which are recognised individually by the mother. The short mixed calls are likely the precursors to echolocation and were given when crawling, the longer "isolation calls" were given in response to stress or isolation. A great variety of calls are given by newborns, but within a week they begin to stabilise into a predictable form. Initially juvenile bats cry almost continuously and mothers respond with long frequency-modulated sinusoidal signals, but by 2 weeks of age the juvenile crawls towards its mother with a mutual exchange of vocalisations. Calls eventually evolve into adult like calls as the constant frequency component increases in frequency (from 40kHz at birth to 65kHz at 1 month) and the repetition rate increases. When a young bat begins to fly it gives repeated short series of staccato pulses at a high repetition rate, these becoming less frequent over the course of the first week when pulses become more adult like, with increased repetition rates during take-off, landing and avoidance of obstacles only. Mother-young pairs also apparently duet when on the wing, giving constant frequency and short frequency-modulated signals. Adults also apparently produce an enormously diverse and complex array of communication sounds.

HUM: Human impact likely negligible, and the species may even be benefitting from damming schemes along the Rio Paraná which are creating more suitable habitat and allowing its expansion east. Considered a bioindicator of water quality in the Ecuadorian Amazon by Tirira (1994).

CON: Globally considered to be of Least Concern by the IUCN, click here to see the latest assessment of the species. Considered stable and common in Paraguay in areas of suitable habitat (López-Gonzalez 2005). This species adaptability, its tolerance of human activity and its preference for large watercourses with slow-moving currents means that it may even be expanding its range as damming schemes along the Rio Paraná tame the previously rapid-flowing river and open up new opportunities for colonisation.

Citable Reference: Smith P (2008) FAUNA Paraguay Online Handbook of Paraguayan Fauna Mammal Species Account 22 Noctilio albiventris.

Last Updated: 25 February 2009.

MAP 22:

Noctilio albiventris

References:

Allen JA 1916 - List of Mammals Collected in Colombia by the American Museum of Natural History Expeditions 1910-1915 - Bulletin AMNH 35: p191-238.

Barquez RM, Giannini NP, Mares MA 1993 - Guide to the Bats of Argentina - Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, Norman, Oklahoma.

Bloedel P 1955 - Hunting Methods of Fish-eating Bats, particularly Noctilio leporinus - Journal of Mammalogy 36: p390-399.

Brown PE, Brown TW, Grinnell AD 1983 - Echolocation, Development and Vocal Communication in the Lesser Bulldog Bat Noctilio albiventris - Behavioural Ecology and Sociobiology 13: p287-298.

Cabrera A 1907 - A New South American Bat - Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 20: p57-58.

Cabrera A 1930 - Breve Sinopsis de los Murciélagos Argentinos - Revista del Centro de Estudios Agron, Veter. Buenos Aires 23: p418-442.

Cabrera A 1958 - Catalogo de los Mamíferos de América del Sur - Revista del Museo Argentino de Historia Natural Bernadino Rivadavia 4:1-307.

Davis WB 1976 - Geographic Variation in the Lesser Noctilio Noctilio albiventris - Journal of Mammalogy 57:p687-707.

Desmarest A 1818 - Noctilion ou Bec de Lièvre - Nouveau Dictionnaire de Histoire Naturelle 23: p14-16.

Desmarest MAG 1820 - Mammalogie ou Description des Espèces de Mammifères. Première Partie, Contenant les Ordres des Binames, des Quadrumanes et des Carnissiers - V. Agasse, Paris, France.

Dobson GE 1876 - Catalog of the Chiroptera - British Museum of Natural History, London.

Eisenberg JF 1989 - Mammals of the Neotropics: Volume 1 The Northern Neotropics - University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Eisenberg JF, Redford KH 1999 - Mammals of the Neotropics: Volume 3 The Central Neotropics - University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Emmons LH 1999 - Mamíferos de los Bosques Húmedos de América Tropical - Editorial FAN, Santa Cruz.

Fenton MB, Audet D, Dunning DC, Long J, Merriman CB, Pearl D, Syme DM, Adkins B, Pedersen S, Wohlgenant T 1993 - Activity Patterns and Roost Selection by Noctilio albiventris (Chiroptera: Noctilionidae) in Costa Rica - Journal of Mammalogy 74: p607-613.

Gardner AL 2007 - Mammals of South America Vol 1: Marsupials, Xenarthrans, Bats and Shrews - University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Goldman EA 1920 - Mammals of Panama - Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collection 69.

Goodwin GG 1928 - Observations on Noctilio - Journal of Mammalogy 9: p104-113.

Goodwin GG 1942 - Mammals of Honduras - Bulletin AMNH 79: p107-195.

Hershkovitz P 1949 - Mammals of Northern Colombia, Preliminary Report Number 5: Bats (Chiroptera) - Proceedings of US National Museum 99: p429-454.

Hershkovitz P 1975 - The Scientific Name of the Lesser Noctilio (Chiroptera) with Notes on the Chauve-souris de la Vallee D´Ylo (Peru) - Journal of Mammalogy 56: p242-247.

Hood CS, Pitocchelli J 1983 - Noctilio albiventris - Mammalian Species 197.

Hoofer SR, Reeder SA, Hansen EW, Van den Bussche RA 2003 - Molecular Phylogenetics and Taxonomic Review of Noctilionid and Vespertilionid Bats (Chiroptera: Yangochrioptera) - Journal of Mammalogy 84: p809-821.

Hooper ET, Brown JH 1968 - Foraging and Breeding in Two Sympatric Species of Neotropical Bats Noctilio - Journal of Mammalogy 49: p310-312.

Howell DJ, Burch D1974 - Food Habits of some Costa Rican Bats - Revista Biologia Tropical 21: p281-294.

Jones JK, Smith JD, Turner RW 1971 - Noteworthy Records of Bats from Nicaragua with a Checklist of the Chiropteran Fauna of the Country - Occasional Papers of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 2: p1-35.

López-Gonzalez C 2005 - Murciélagos del Paraguay - Biosfera Numero 9.

Miller GS 1906 - Twelve New Genera of Bats - Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 19: p83-87.

Myers P, Espinosa R, Parr CS, Jones T, Hammond GS, Dewey A 2006 - The Animal Diversity Web (online). Accessed December 2008.

Myers P, Wetzel RM 1983 - Systematics and Zoogeography of the Bats of the Chaco Boreal - Miscellaneous Publications of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan 165.

Novak RM 1991 - Walker´s Mammals of the World 5th Ed Volume 1 - Johns Hopkins, Baltimore.

d´Orbigny AD 1837 - Voyage dans l´Amerique Méridionale (le Bresil, la République Oriental de Uruguay, la République Argentine, la Patagonie, la République du Chile, la République de Bolivia, la République du Perou) Executé Pendant les Années 1826, 1827, 1828, 1829, 1830, 1831, 1832, 1833 - Pitois-Levrault et cie, Paris, Strasbourg.

d´Orbigny AD, Gervais P 1847 - Voyage dans l´Amerique Méridionale (le Bresil, la République Oriental de Uruguay, la République Argentine, la Patagonie, la République du Chile, la République de Bolivia, la République du Perou) Executé Pendant les Années 1826, 1827, 1828, 1829, 1830, 1831, 1832, 1833 - Pitois-Levrault et cie, Paris, Strasbourg.

Osgood WH 1910 - Mammals from the Coasts and Islands of Northern South America - Field Museum of Natural History Zoology Series 10: p23-32.

Osgood WH 1912 - Mammals from Western Venezuela and Eastern Colombia - Field Museum of Natural History Zoology Series 10: p33-66.

Presley SJ 2005 - Ectoparasitic assemblages of Paraguayan bats: ecological and evolutionary perspectives - Texas Tech University PhD Dissertation.

Rasweiler JJ 1977 - Preimplantation Development, Fate of Zona Pellucida and Observations on the Glycogen-rich Oviduct of the Little Bulldog Bat Noctilio albiventris - American Journal of Anatomy 150: p269-300.

Rengger JR 1830 - Naturgeschicte der Saeugethiere von Paraguay - Basel.

Sanborn CC 1949 - Mammals from the Rio Ucayali, Peru - Journal of Mammalogy 30: p277-288.

Schnitzler HU, Kalko EKV, Kaipf I, Grinnell AD 1994 - Fishing and Ecolocation Behaviour of the Greater Bulldog Bat Noctilio leporinus in the Field - Behavioural Ecology and Sociobiology 35: p327-345.

Spix J de 1823 - Simiarum et Vespertilionum Brasiliensum Species Novae: Ou Histoire Naturelle des Esepecies Nouvelles de Singes et Chauves-souris Observées et Recueilles Pendant le Voyage dans L´interieur de Bresil - Typis Francisi Serephici Hübschmanni, Monaco.

Taddei VA, de Seixas RB, Dias AL 1986 - Noctilionidae (Mammalia, Chiroptera) do Sudeste Brasileiro - Ciencia e Cultura 38: p904-916.

Tamsitt JR, Valdivieso D 1963 - Notes on Bats from Leticia, Amazonas, Colombia - Journal of Mammalogy 44: p263.

Thomas O 1920 - On Mammals of the Lower Amazons in the Goedli Museum, Para - Annals and Magazine of Natural History Series 9 6: p266-283.

Tirira D 1994 - Aspectos Ecológicos del Murciélago Pescador Menor Noctilio albiventris (Chiroptera: Noctilionidae) y su Uso como Bioindicador en la Amazona Ecuatoriana - Tesis de Licenciatura, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Ecuador, Quito.

Wenzel RL, Tipton VJ, Kiewlicz A 1966 - The Streblid Batflies of Panama (Diptera Calypterae: Streblidae) p405-675 in Wenzel EL, Tipton VJ Ectoparasites of Panama - Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago.

Whitaker JO, Findley JS 1980 - Foods Eaten by some Bats from Costa Rica and Panama - Journal of Mammalogy 61: p540-544.

Yunker CE, Radovsky FJ 1980 - Parasitic Mites of Suriname XXXVI: A New Genus and Two New Species of Macronyssidae (Acari: Mesostigmata) - Journal of Medical Entomology 17: p545-554.