Tolypeutes matacus (Desmarest 1804) Image Gallery

TAX: Class Mammalia; Subclass Theria; Infraclass Eutheria; Order Cingulata; Family Dasypodidae; Subfamily Tolypeutinae (Myers et al 2006). The genus Tolypeutes was defined by Iliger in 1811. There are two known species according to the latest revision (Gardner 2007) only one of which is present in Paraguay. Desmarest´s (1804) description was based on de Azara´s (1801) "Le Tatou Mataco". Larrañaga´s (1923) description was based on de Azara´s (1802) "Mataco". The species is monotypic (Gardner 2007). Synonyms adapted from (Gardner 2007):

Dasypus octodecimcinctus GI Molina 1782:305. Type locality "Nel Cujo" Chile, identified as Provincia Mendoza, Argentina by Tamayo (1968). Name preocuppied by Dasypus octodecimcinctus Erxleben (1777) =Cabassous unicinctus (Linnaeus 1758).

Lor[icatus], matacus Desmarest 1804:28. No locality mentioned. Based on de Azara (1801). Sanborn (1930) restricted the type locality to Tucumán, Argentina.

[Dasypus] brachyurus G.Fischer 1814:130. Type localities "Tecumanis et Circa Buenos-Ayres".

Tolypeutes globules Illiger 1815:108. Nomen nudum.

T[olypeutis] octodecimcinctus Olfers 1818:221. Name combination.

Dasypus apar Desmarest 1822:367. Type localities "Le Tecuman et les campagnes découverts dans les environs de Buenos-Ayres, à partir du 36º. degré et gagnant vers le sud".

Tatusia apar Lesson 1827:310. Name combination.

Tolypeutes conurus I. Geoffroy St.Hilaire 1847:137. Type localities "Tecuman et des pampas de Buenos-Ayres (Argentina), et de la province de Santa Cruz de la Sierra (Bolivia).

Dasypus [(Tolypeutes)] conurus Burmeister 1861:436. Name combination.

Dasypus aparoides P.Gervais 1869:132. Nomen nudum.

Tolypeutes muriei Garrod 1878:223. Type locality unknown. Sanborn (1930) restricted the type locality to Bahía Blanca, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Tolypoides bicinctus Grandidier & Neveu-Lemaire 1905:370. Type locality "l´Amérique du Sud" restricted to "environs de Tarija" Bolivia by Grandidier & Neveu-Lemaire (1908).

Tolypeutes matacus Osgood 1919:33. First use of current name.

D[asypus]. globulosus Larrañaga 1923:343. Type locality "Australem plagam bonaerensem" Based on de Azara (1802).

Tolypeutes matacos Yepes 1928:478. Incorrect spelling.

Tolypeutes tricinctus matacus Sanborn 1930:66. Name combination.

Tolypeutes tricinctus muriei Sanborn 1930:66. Name combination.

ENG: Southern Three-banded Armadillo (Gardner 2007), Three-banded Armadillo (Neris et al 2002, Parera 2002), La Plata Three-banded Armadillo (Merritt 1976), Southern Domed Armadillo (Gardner 2007).

ESP: Tatu bolito (Villalba & Yanosky 2000), Quirquincho bola (Redford & Eisenberg 1992, Neris et al 2002), Tatú bola (Parera 2002), Mataco (Parera 2002).

GUA: Tatu bolita (Neris et al 2002), Tatu ai MPA (Villalba & Yanosky 2000), Chachu kuyú Ac (Villalba & Yanosky 2000), Tatu apepú (Parera 2002). "Bolita" and its variations which feature in the Guaraní and Spanish names refer to the species defensive behaviour of curling up into a ball.

DES: Heavily-armoured with the carapace extending almost to the feet, the Southern Three-banded Armadillo is generally sandy-yellow coloured in Paraguay (blackish individuals being found in some other parts of their range). Typically the aspect of the body is hinge-like, with the back steeply rounded and the two halves of the carapace forming an open V-shape at their lower edge. The triangular head plate is remarkably thick and robust and the main carapace consists of two huge plates (scapular and pelvic) separated by 2 to 4 movable bands (generally three). The individual scales are notable for their hexagonal rosette form. The sides of the body are not attached to the carapace, allowing a certain amount of flexibility of movement within the "shell". Long, thick, pale sandy-coloured bristles sprout along the lower edge of the carapace. The ears are large and somewhat flattened with a roughened edge. The iris is brown. The underbelly is quite heavily furred with dark brownish hair. Bare skin on the sides of the face is similarly dark brown, but the tip of the snout and nose are pinkish. The inflexible tail is covered in scutes, short and thick, triangular in form, and blunt-ended, fitting perfectly alongside the head when the animal rolls into its defensive ball. The legs are short and strong, armoured but with a covering of thick brownish hair. The forefeet bears four toes with greatly elongated claws particularly on the middle toes. The hindfeet also bear five toes, the second, third and fourth almost unified, flattened and hoof-like, the first and fifth with "normal" claws. CR: Occipitonasal length 60mm. Relatively long and tubular rostrum. (Diaz & Barquez 2002). DF: Armadillos lack true teeth, but possess a series of "molariform" teeth that do not follow the standard mammal dental formula. 9/9 = 36. All molariforms are located in the maxillar, differentiating Tolypeutes from Chaetophractus and Euphractus. CN: 2n=38 This species lacks truly acrocentric autosomes and the diploid number is lower than any other armadillo (Nowak 1991).

TRA: Given the dry areas in which this species lives footprints are usually only encountered in areas of loose soil or after rains. The print of the forefeet is distinctive, leaving marks of three triangular forward-facing toes, the middle one approximately twice the length of the outer two. The unusual structure of the hind print leaves a peculiar "compound" print in soft soil which may appear to be made by two feet. For the most part the armadillo walks on the front part of the foot, with the posterior part, complete with its own pads, leaving its impression only in softer soil. FP: 3.7 x 2.7cm HP: 3.4 x 2.7cm. PA: 22cm. (Villalba & Yanosky 2000).

MMT: A small armadillo with a steeply-rounded, hinge-like carapace. TL: (25-30cm); HB: 25.7cm (21.5-27.3cm); TA: 6.37cm (5.5-8cm); FT: 4.23cm (2.5-4.7cm); EA: 2.28cm (1.9-4.1cm); WT: 1.1kg (0.8-1.5kg). (Parera 2002, Nowak 2001, Ceresoli et al 2003, Redford & Eisenberg 1992, Diaz & Barquez 2002). The following additional measurements were taken from two individuals at PN Tte Enciso, Departamento Boquerón during July 2006 - Head Length: - 7.4-7.7cm; TA: 5.7-6.3cm; EA: 2.62cm; Carapace Width: 11.5-11.6cm; Longest Claw on Forefoot: 2.65cm (P. Smith unpubl.).

SSP: The most instantly recognisable of the small armadillos due to its hard, inflexible carapace and presence of just three movable bands. Furthermore, contra the stereotypical image that many people have of armadillos rolling into a ball to protect itself, the genus Tolypeutes are the only armadillos that do so, making this behaviour diagnostic of the species in Paraguay.

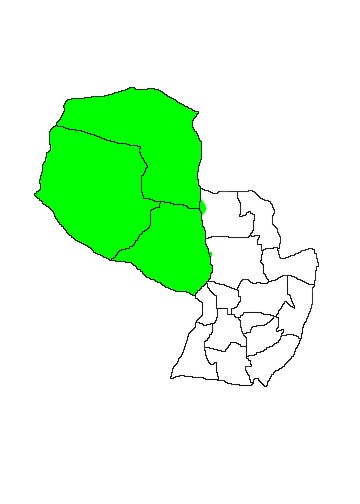

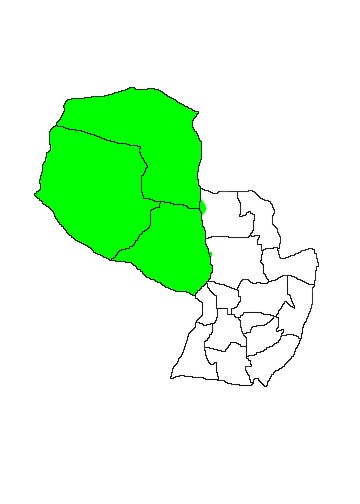

DIS: Occurs from southeastern Bolivia, through the southwestern and western cerrado belt of Brazil, the Paraguayan Chaco to northern and central Argentina in the Provinces of Formosa, Chaco, northern Santa Fé, Santiago del Estero, eastern Salta and Jujuy, Tucúman, Rioja, Catamarca, Córdoba, San Juán, La Pampa, San Luís, extreme northeastern Mendoza and southern Buenos Aires. References to the species presence in Chile probably stem from GI Molina (1782) when Provincia Mendoza formed part of Chile (Gardner 2007). The species is declining rapidly in the southern parts of its Argentinian range. In Paraguay it is most abundant in the Dry Chaco departments of Boquerón and Alto Paraguay, less common in Presidente Hayes and there are marginal records from extreme western Departamentos Concepción and San Pedro (Neris et al 2002).

HAB: This species is confined to the Chaco where it is most abundant in xerophytic areas, typically thorny Chaco forest and scrub. In the area around the Mennonite colonies of the Central Chaco it may be found in agricultural land and around rural dwellings provided patches of scrubby forest are maintained nearby. In the Humid Chaco it occurs in palm savanna and gallery forest (Brooks 1995). It chooses to take refuge in forested areas but often forages in more open habitats. At PN Tte Enciso, Departamento Boquerón, the species frequently forages in the area close to the accommodation despite the presence of artificial lights. Parera (2002) states that it does not occur in areas with greater than 700mm annual rainfall.

ALI: Three-banded Armadillos are opportunistic insectivores that feed mainly on the surface of the ground, only occasionally digging shallow holes into ant and termite nests. They do not perform extensive digging projects in order to obtain food stuffs, given that in the dry areas in which they live the soil is often so hard as to have the consistency of concrete and requires considerable force even to break the surface with a spade. Considered to be largely myrmecophagous, feeding on ants and termites, but other soft-bodied invertebrates are also taken and they regularly scratch at tree trunks in search of arthropods (Redford & Eisenberg 1992, Parera 2002). In the Brazilian cerrado three stomachs were found to contain the non-colonial termite Syntermes molestus, spiders and ants of the genus Camponotus. During a study in northeastern Santiago del Estero, Argentina, 66 stomachs were analysed by Bolkovic et al (1995) which showed the diet of wild individuals to consist of 70% invertebrate material, 20% fruits and 10% unidentified material, and that the presence of different items in the diet was seasonal. All invertebrates found lived at ground level or below and invertebrate larvae were the most common item in the diet, especially Coleoptera larvae. Termites were shown to be an important item in the diet from July to November but less prominent at other times of year. The following ant species were recorded Ponerinae; Pseudomyrmicinae (Pseudomyrmex); Dorylinae (Crematogaster, Neivamyrmex, and Novamyrmex); Myrmycinae (Acromyrmex, Pheidole, Elasmopheidole, Solenopsis, and Wasmannia); Dolechoderinae (Dorymyrmex); Formicinae (Camponotus and Brachymyrmex). Lepidopteran larvae and pupae were most prominent during July and August. Of the fleshy fruits present Zyzyphus mistol (Rhamnaceae) was the most prominent, being a fruit that stays on the ground for several weeks after falling. Other fruits reflected seasonal abundance, but fruits of Castela coccinea (Simaroubaceae) were avoided and the presence of phenols, alkaloids and triterphenoids probably acts to deter the armadillos which seek their food by smell. A considerable quantity of soil was found to be ingested, making of up to 40% volume by weight in some stomachs and an extraordinary 92% volume by weight in one stomach. Items were found intact in the stomach, suggesting that they do not chew their food and local reports suggested that the animals deliberately ingest soil, possibly to assist with digestion. Intact seeds in the stomach suggest that the species may play an important role in seed dispersal of certain plants. Parera (2002) reports that in the Argentinian Chaco the mostly insectivorous diet is also supplemented with fruit. Captive individuals took fruit, leaves, boiled rice, bread soaked in milk or tea, ants and their eggs and larvae, and mealworms (Nowak 1991). Additional items fed to captive individuals include boiled egg, grated carrot, honey, lean horsemeat and cod-liver oil (Bolkovic et al 1995).

REP: Several males pursue single females in oestrus hoping for the opportunity to mate. Most births happen from October to January, meaning that mating takes place from July to October (Redford & Eisenberg 1992). Neris et al (2002) state that the Paraguayan breeding season is from May to October or November, somewhat earlier than the dates stated by Redford & Eisenberg, but Merritt (1976) concurred with them, quoting November to January as the Paraguayan breeding season. Parera (2002) records breeding in Argentina from September to February. A single young is born after a gestation period of 120 days - though Neris et al (2002) indicate that twins occasionally occur. Reproductive rate is slow, with an average of 1.5 young per female per annum (Abba et al 2007). Newborns are miniature versions of adults, with claws fully-developed and hardened. The carapace is flexible and has a leathery texture, but the markings of the individual scutes are apparent from the beginning. From birth newborns are able to walk and roll into a ball. Young first open their eyes and ear pinnae at 22 days and are weaned in 10 weeks (72 days). Sexual maturity is reached at 3 to 5 years.

BEH: General Behaviour Solitary for much of the year, small groups gather only during the breeding season when several males pursue single females in oestrus (Neris et al 2002). Though sometimes active during the day, animals observed at PN Tte Enciso, Departamento Boquerón during July 2006 were only encountered at night and major activity peaks are likely affected by temperature and rainfall (P. Smith pers. obs., Redford & Eisenberg 1992). Specimens were also found to be active during the first hour of daylight at PN Defensores del Chaco, Departamento Boquerón during September 2006. Neris et al (2002) states that the species becomes more diurnal during the breeding season. In Mato Grosso, Brazil most encounters with the species were between midday and 18.00h. Despite well-developed claws on the forefeet, this species does not dig its own burrows, preferring to re-use burrows made by other armadillos and burrowing mammals. This species walks on the soles of the hindfeet and only the tips of the claws of the forefeet are in contact with the ground (Vizcaíno & Milne 2002). Defensive Behaviour The first reaction of this armadillo when faced with a potential predator is to run, the legs moving rapidly like a clockwork toy and the path chosen irregular and zig-zagging to avoid vegetation. The eyesight is poor and frequently the animal will almost collide with static objects, pulling up suddenly before changing direction and accelerating again. Unlike many other armadillos they do not dig to escape danger and do not immediately head for their hole and can usually be captured fairly easily by hand after a short pursuit provided their path does not take them into dense thorny scrub. Upon capture the armadillo rolls into a ball, the triangular head plate fitting tightly into the extensive scapular plate posteriorly and anteriorly jig-saw-like with the triangular tail so that the soft underbelly of the animal protected by the continuous covering of armour. Frequently the shell remains slightly open and if an attempt is made to touch the underbelly the shell snaps shut with remarkable force (Nowak 1991). Villalba & Yanosky (2002) state that the force of closing is capable of damaging a human finger and likely acts as a substantial deterrent against predators. If left unmolested the animal begins to unroll slowly, suddenly bursting into a run (Sanborn 1930). Handled animals typically half unroll the shell and begin to defecate. (P. Smith pers. obs.). The longevity of this species is 12 to 15 years. Enemies The carapace of this species is especially rigid and it is common to find hollowed-out, dried carapaces in the Dry Chaco, often with the head still attached (P. Smith pers. obs.). The original cause of mortality is not always clear, but the "cleaning" of the remains is probably due to vultures and Southern Crested-Caracaras. It provides an effective defence against foxes and small cats, and it is possibly even enough to dissuade large felines. Interestingly enough remains of this species have been found in the pellets of Burrowing Owls in Santiago del Estero, Argentina. Parasites Members of this species often have a heavy parasite load and individuals in PN Tte Enciso, Departamento Boquerón frequently carried ticks (Acari) on their underbelly (P.Smith pers. obs.). Navone (1990) recorded the following parasites of this species in the Argentinean Chaco - Nematodes: Aspidodera scoleciformis (Aspidoderidae), Pterygodermatites chaetophracti (Rictularidae), Dipetalonema anticlava (Dipetalonematidae), Mazzia bialata (Cosmocercidae), Maciela elongata and Moennigia virilis (Molineidae); Cestode Mathevotaenia matacus (Anoplocephalidae); Acanthocephala Travassosia sp (Oligacanthorrhinchidae).

VOC: A captured individual at PN Tte Enciso, Departamento Boquerón made quiet grunting noises similar to a domestic guinea-pig (P.Smith pers. obs.)

HUM: This armadillo is confiding and easily captured by hand, making it a popular pet for indigenous groups and the "preferred armadillo for the table" in the Chaco (Hugo del Castillo pers. comm.). It is said to have the best flavour amongst the armadillos, but it is uncertain how much of this is due to its palatability and how much is due to wishful thinking with it being the most abundant and easily captured species in the area. In Santiago del Estero, Argentina, it was found to constitute 55% of the wild fauna in the diet of local people. Tolypeutes are the only armadillos that roll into a ball to protect themselves, but this atypical behaviour has become associated with a "stereotypical armadillo" in the minds of many people across the globe.

CON: The Southern Three-banded Armadillo is considered Low Risk, near threatened by the IUCN, click here to see their latest assessment of the species. The Centro de Datos de Conservación in Paraguay consider the species to be persecuted by humans in Paraguay and give it the code N3. The species is not listed by CITES. The major threats to this species appear to be hunting for food, capture as a pet and burning. The species has poor eyesight and a somewhat haphazard way of escaping danger and burning of forest or grassland undoubtedly claims many victims. Exportation of the species occurs across its range and there is a high mortality rate during this process with upwards of 80% of the specimens sent to Europe dying en route. Currently the Dry Chaco does not pose any real conservation concern, its isolation, low population and extreme climactic conditions are not attractive for agriculture, but the low price of land in the area means that cattle ranchers are beginning to purchase properties in the area. Persistent rumours of undiscovered oil and gas reserves in the Chaco may also make the area vulnerable to prospecting in future. The species is able to tolerate moderate conversion to agriculture but too much habitat perturbation is likely to have a negative effect on populations, furthermore the slow reproductive rate of this species hinders the ability of populations to recover quickly. The species is present and common in several protected areas in the Chaco and its survival in Paraguay seems secure for the moment. However in Brazil the species is in widespread decline and populations are estimated to have decreased by 30% over the last decade. Population densities in Mato Grosso, Brazil were estimated at 0.96/km2 in cerrado, 0.59/km2 in secondary forest and 0.42/km2 in deciduous forest. Wetzel (1982) however estimated a population density of 7/km2. An estimate of 1.9/km2 has been quoted for Chaco habitat. A self-sustaining captive population is present in the USA, notably at the Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago (Abba et al 2007), but captive individuals often suffer from pathologies and stereotyped behaviours (Parera 2002).

Citable Reference: Smith P (2007) FAUNA Paraguay Online Handbook of Paraguayan Fauna Mammal Species Account 7 Tolypeutes matacus.

Last Updated: 23 June 2009.

References:

Abba A, Cuellar E, Meritt D, Porini G, Superina M, members of the Edentate Specialist Group 2006. Tolypeutes matacus. In: IUCN 2007. 2007 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 23 December 2007.

Azara F de 1801 - Essais sur l´Histoire Naturelle des Quadrupèdes de la Province du Paraguay - Charles Pougens, Paris.

Azara F de 1802 - Apuntamientos para la Historia Natural de los Quadrúpedos del Paraguay y Rio de la Plata - La Imprenta de la Viuda de Ibarra, Madrid.

Bolkovic ML, Caziani SM, Protomastro JJ 1995 - Food Habits of the Three-banded Armadillo (Xenarthra: Dasypodidae) in the Dry Chaco of Argentina - Journal of Mammalogy 76:p1199-1204.

Brooks DM 1995 - Distribution and Limiting Factors of Edentates in the Paraguayan Chaco - Edentata 2: p10-15.

Burmeister H 1861 - Reise durch die La Plata-Staaten mit Besonderer Rücksicht auf die Physische Beschaffenheit und den Culturzustand der Argentinischen Republik Ausgeführt in den Jahren 1857, 1858, 1859 und 1860 - HW Schmidt, Halle.

Cartés JL 2007 - Patrones de Uso de los Mamíferos del Paraguay: Importancia Sociocultural y Económica p167-186 in Biodiversidad del Paraguay: Una Aproximación a sus Realidades - Fundación Moises Bertoni, Asunción.

Ceresoli N, Jimenez GT, Duque EF 2003 - Datos Morfómetricos de los Armadillos del Complejo Ecológico de Sánz Peña, Provincia del Chaco, Argentina - Edentata 5: p35-37.

Desmarest AG 1804 - Tableau Méthodique des Mammifères in Nouveau Dictionnaire d´Histoire Naturelle, Appliquée aux Arts, Principalement à l`Agriculture, à l`Économie Rurale et Domestique: Par une Société de Naturalistes et d`Agriculteurs: Avec des Figures Tirées des Trois Règnes de la Nature - Deterville Vol 24, Paris.

Desmarest AG 1822 - Mammalogie ou Description des Espèces de Mammifères Seconde Partie: Contenant les Ordres de Rongeurs, des Édentes, des Pachydermes, des Rumainans et des Cetacés - Veuve Agasse, Paris.

Díaz MM, Barquez RM 2002 - Los Mamíferos del Jujuy, Argentina - LOLA, Buenos Aires.

Erxleben JCP 1777 - Systema Regni Animalis per Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, Varietates cun Synonimia et Historial Animalium: Classis 1 Mammalia - Weygandianus, Leipzig.

Fischer G 1814 - Zoognosia Tabulis Synopticis Illustrata: Volumen Tertium. Quadrupedum Reliquorum, Cetorum et Monotrymatum Descriptionen Continens - Nicolai Sergeidis Vsevolozsky, Mosquae.

Gardner AL 2007 - Mammals of South America Vol 1: Marsupials, Xenarthrans, Shrews and Bats - University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Garrod AH 1978 - Notes on the Anatomy of Tolypeutes tricinctus with Remarks on other Armadillos - Proceedings of Zoological Society of London 1878: p222-230.

Geoffroy St.-Hilaire I 1847 - Note sur le Genre Apar, sur ses Espèces et sur ses Caractères, Établis jusqu´à Présent d´après un Animal Factice - Rev. Zool. Paris 10: p135-137.

Grandidier G, Neveu-Lemaire M 1905 - Description d´une Nouvelle Espèce de Tatou, Type d´un Genre Nouveau Tolypoïdes bicinctus - Bull. Museu Histoire Naturelle de Paris 7: p370-372.

Grandidier G, Neveu-Lemaire M 1908 - Observations Relatives à Quelques Tatou Rares ou Inconnus Habitant la "Puna" Argentine et Bolivienne - Bull. Museu Histoire Naturelle de Paris 14: p4-7.

Illiger K 1815 - Ueberblick der Säugthiere nach ihrer Vertheilung über die Welttheile - Abhandl. König. Akad. Wiss. Berlin 1804-1811: p39-159.

Jones ML 1982 - Longeivty of Captive Mammals - Zool. Garten 52: p113-128.

Larrañaga A 1923 - Escritos - Instituto Històrico y Geogràfico del Uruguay 2: p1-512.

Linnaeus C 1758 - Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species cum Characteribus, Diferentiis, Synonymis, Locis. Editio Decima. - Laurentii Salvii, Holmiae.

Lesson RP 1827 - Manuel de Mammalogie ou Histoire Naturelle des Mammifères - Roret, Paris.

Merritt DA 1976 - The La Plata Three-banded Armadillo Tolypeutes matacus in Captivity - International Zoo Yearbook 16: p153-155.

Molina GI 1782 - Saggio sulla Storia Naturale del Chili - Stamperia di S.Tommaso d´Aquino, Bologna.

Möller-Krull M, Delsuc F, Churakov G, Marker C, Superina M, Brosius J, Douzery EJP, Schmitz J 2007 - Retroposed Elements and Their Flanking Regions Resolve the Evolutionary History of Xenarthran Mammals (Armadillos, Anteaters and Sloths) - Molecular Biology and Evolution 24: p2573-2582

Myers P, Espinosa R, Parr CS, Jones T, Hammond GS, Dewey A 2006 - The Animal Diversity Web (online). Accessed December 2007.

Navone GT 1990 - Estudio de la Distribución, Porcentaje y Microecología de los Parásitos de Algunas Especies de Edentados Argentinos - Studies in Neotropical Fauna and Environment 25: p199-210.

Neris N, Colman F, Ovelar E, Sukigara N, Ishii N 2002 - Guía de Mamíferos Medianos y Grandes del Paraguay: Distribución, Tendencia Poblacional y Utilización - SEAM, Asunción.

Nowak RM 1991 - Walker´s Mammals of the World 5th Ed Volume 1 - Johns Hopkins, Baltimore.

Olfers I 1818 - Bemerkungen zu Illiger´s Ueberblick der Säugthiere nach ihrer Vertheilung über die Welttheile p292-237 in Neue Bibliothek der Wichtigsten Reiseschreibungen... Vol 15 Heft 2 - Weimar.

Osgood WH 1919 - Names of Some South American Mammals - Journal of Mammalogy 1: p33-36.

Parera A 2002 - Los Mamíferos de la Argentina y la Región Austral de Sudamérica - Editorial El Ateneo, Buenos Aires.

Redford KH, Eisenberg JF 1992 - Mammals of the Neotropics: Volume 2 The Southern Cone - University of Chigaco Press, Chicago.

Sanborn CC 1930 - Distribution and Habits of the Three-banded Armadillo Tolypeutes - Journal of Mammalogy 11: p61-68.

Tamayo HM 1968 - Los Armadillos Descritos por JI Molina - Notic. Mensual Museo Nacional Santiago - 12: p3-11.

Villalba R, Yanosky A 2000 - Guía de Huellas y Señales: Fauna Paraguaya - Fundación Moises Bertoni, Asunción.

Vizcaíno SF, Milne N 2002 - Structure and Function in Armadillo Limbs (Mammalia: Xenarthran: Dasypodidae) - Journal of Zoological Society of London 257: p117-127.

Wetzel RM 1982 - Systematics, Distribution, Ecology and Conservation of South American Edentates - Pymatuning Lab. Ecol. Special Publication 6: p345-375.

Yepes J 1928 - Los "Edentata" Argentinos. Sistemática y Distribución - Revista Universidad de Buenos Aires Serie 2a 1:p461-515.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many thanks to Mariella Superina for assisting with obtaining some of the references used in the construction of this species account.

MAP 7:

Tolypeutes matacus

Designed by Paul Smith 2006. This website is copyrighted by law.

Material contained herewith may not be used without the prior written permission of FAUNA Paraguay.

Photographs on this web-site are used with permission.