Chaetophractus villosus (Desmarest 1804) Image Gallery

TAX: Class Mammalia; Subclass Theria; Infraclass Eutheria; Order Cingulata; Family Dasypodidae; Subfamily Euphractinae (Myers et al 2006, Möller-Krull et al 2007). Three species are recognised in this genus, two are present in Paraguay. Chaetophractus is taken from the Greek meaning "hairy shell", the specific name villosus is from the Latin and also means "hairy". The genus Chaetophractus was defined by Fitzinger (1871). The genus Chaetophractus was defined by Fitzinger in 1871. The species in monotypic. The species description is based upon de Azara´s (1801) "Le Tatou Velu" Formerly placed in the Chaetophractinae, Möller-Krull et al (2007) provided DNA evidence that demonstrated their position within the Euphractinae. Synonyms adapted from Gardner (2007):

Dasypus octocinctus Molina 1782:305. Type locality "Nel Cujo" Chile (=Provincia Mendoza, Argentina). Preoccupied by Dasypus octocinctus Schreber 1774 (=Dasypus novemcinctus Linnaeus 1758).

lor[icatus]. villosus Desmarest 1804:28. Based on de Azara (1801). Type locality "Les Pampas", Buenos Aires, Argentina.

[Dasypus] villosus G.Fischer 1814:125. Name combination.

T[atus]. villosus Olfers 1818:220. Name combination.

Tatusia villosa Lesson 1827:312. Name combination.

Dasypus (Tatusia) villosus Rapp 1852:10. Name combination.

Dasypus [Euphractus] villosus Burmeister 1861:427. Name combination.

Euphractus villosus Gray 1865:376. Name combination.

Chaetophractus villosus Fitzinger 1871:268. First use of current name.

[Dasypus (Choetophractus)] villosus Trouessart 1898:1146. Name combination.

D[asypus]. pilosus Larrañaga 1923:343. Type locality "Campis Bonaerensibus". Preoccupied by Dasypus pilosus (Fitzinger 1856).

Euphractus (Chaetophractus) villosus Moeller 1968:514. Name combination.

ENG: Greater Hairy Armadillo, Larger Hairy Armadillo (Eisenberg & Redford 1999), Large Hairy Armadillo (Neris et al 2002), Big Hairy Armadillo (Gardner 2007).

ESP: Pichi peludo (Neris et al 2002), Quirquincho grande (Eisenberg & Redford 1999), Tatu pecho amarillo (Cuéllar & Noss 2003), Tatú peludo (Parera 2002).

GUA: Tatu poju´i (Neris et al 2002). "Poju" refers to the needle-like claws of the forefeet, the addition of "i" meaning small. In other words "little Tatu poju", or small version of Euphractus sexcinctus, the species commonly known as Tatu poju in Paraguay.

DES: A medium-large armadillo with conspicuous blackish dorsal hairs and a somewhat flattened carapace. Possesses 7 or 8 movable bands between the scapular and pelvic shields and at least 2 neck bands. Small individuals possess 2 to 4 small openings in the posterior part of the pelvic shield which are glandular openings and produce an odorous secretion. The head shield is large, notably downcurved in profile on the forehead and reaches almost to the point of the snout. It is composed of small disorganised scutes and has a distinct posterior border. There is no spur behind the eye. Head and carapace dark reddish-brown, somewhat paler and more tan coloured on the borders. Ears are medium-sized and dark brown in colour. Sides of head and ventral skin dark brown with long tufts of hair on cheeks, legs and throat, the hairs of the underparts being slightly paler than those of the dorsal surface. Legs short but robust with flattened claws on all toes CR: No information. DF: Armadillos lack true teeth, but possess a series of "molariform" teeth that do not follow the standard mammal dental formula. 9/10 = 38. First molariform located in the premaxillary as in Euphractus. CN: 2n=60. FN=88 or 90. Males have not been karyotyped (Gardner 2007).

TRA: No information.

MMT: A medium-sized armadillo with a flattened carapace. TL: 43.67cm (38.6-55cm); HB: 29.11cm (26.1-34.4cm); Head 10cm; Head Width 11cm; TA: 11.2-15.6cm; Tail Diameter at Base 8cm; FT: 6.17cm (5-7cm); EA: 2.4cm (2.2-3.1cm); Mouth 7x4cm; WT: 2.37kg (1-3.89kg) They are capable of depositing large amounts of fat and captive individuals may be much heavier than wild individuals; WN: 127.29g (108-155g); Claws of Forefeet: 1.5-2.5cm. (Parera 2002, Eisenberg & Redford 1999, Neris et al 2002, Redford & Eisenberg 1992, Ceresoli et al 2003, Olocco-Diz & Duggan 2004, Olocco-Diz et al 2006).

SSP: This species is easily confused with the larger Euphractus sexcinctus with which it overlaps throughout its Paraguayan range - though note that this species is absent from much of the Orient. In general Euphractus is more yellowish in colour with pale guard hairs on the carapace, this species somewhat more reddish-tan with dark brownish hairs. Chaetophractus villosus is hairier overall (though the dark hairs against the dark shell are not always conspicuous) with more obvious tufts of hair on the cheek, throat and legs. Though the number of movable bands is variable in both species, this species never has less than 7 whilst Euphractus may occasionally have 6. Examining the head plate Euphractus can be seen to have a "spur" behind the eye and often a line of small scales beneath the eye which are both absent in this species. Note also the rounded forehead in profile of the Chaetophractus when compared to the flattened forehead of Euphractus. Furthermore the large, well-organised scales on the head shield of Euphractus are in contrast to the smaller, disorganised scales of Chaetophractus which also usually shows a well-defined posterior border to the head shield. At least two neck bands are present between the head shield and the scapular plate in this species, only one is present in Euphractus. The other member of the genus Chaetophractus vellerosus is considerably smaller with longer ears.

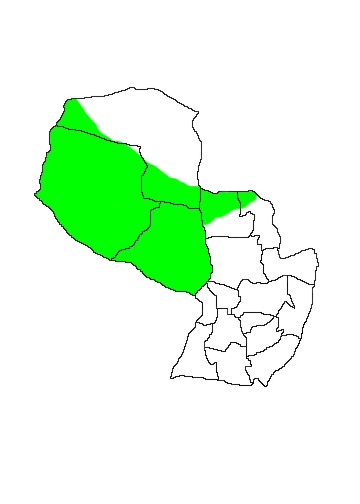

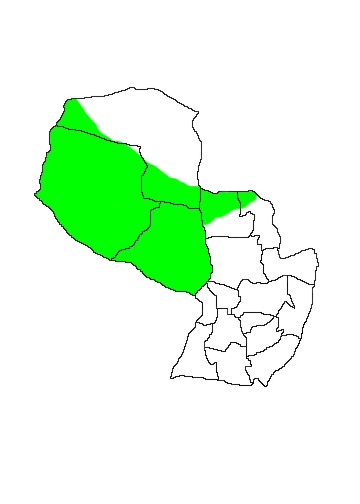

DIS: Widely distributed in the Southern Cone of South America from Brazil and extreme western Brazil to Argentina and eastern Chile south to Magallanes, though its distribution in that country is somewhat disjunct. In Argentina it is the commonest and most widespread armadillo, being found throughout Patagonia north to Provincias Buenos Aires and Cordóba, and extending further north through the central zone of the country to Provincias Santiago del Estero and Chaco. It has been introduced into Tierra del Fuego, Argentina. In Paraguay it is present throughout the Chaco, though considerably less common in the humid Chaco. According to Neris et al (2002) they occur in eastern Paraguay in areas of cerrado in the drier areas of the northern Orient in Departamentos Concepción and Amambay. However this was rejected by the Edentate Specialist Group (2004) who insist that the species is absent from eastern and southern Paraguay and confined to the Dry Chaco. Confusion with the superficially similar Euphractus sexcinctus may be responsible for the Oriental records. This is the commonest large armadillo in the Paraguayan Chaco.

HAB: Confined to xerophytic areas of the Chaco where it occurs in matorral, edges of Chaco woodland, ranchland and agricultural areas. Burrows are generally located in bushy areas though they tend to forage in more open habitats, including along roads - they are often seen by the side of the Ruta Trans-Chaco in Departamento Boquerón. Frequently found close to human habitation.

ALI: A generalist omnivore, their ability to survive on a low water diet is one of the reasons for their success in arid environments where other armadillos are less abundant (Greegor 1975). Analysis of stomach contents reported in Cuéllar & Noss (2003) revealed that the species feeds primarily on fruits (60% of diet) in the Bolivian Chaco, especially Guayacán Caesalpinia paraguariensis, Algarrobo Prosopis chilensis, Mistol Ziziphus mistol, Yvyra hû Sideroxylon obtusifolium and the cacti Quiabentia pflanzil, with the addition of insect material such as beetles, termites and ants. Neris et al (2002) describe it as principally a scavenging species feeding largely on carrion and roadkill. Parera (2002) notes that the diet may change through the year with invertebrates predominating in winter and vegetable matter in summer. In areas of human habitation they may raid rubbish bins in search of food or chicken coups for eggs. They may even construct temporary burrows under or even into carcasses to exploit maggots. Rarely they may drive the rostrum into soft soil and turn the body in a circular motion to form a conical hole in order to obtain insects. (Nowak 1991). In captivity they have adapted to commercial dog and cat foods supplemented with fruit, vegetables, eggs and large amounts of live insects, but as they show a tendency towards obesity should not be fed for at least one day each week. (Ratajszczak & Trzesowska 1997). A pair of captive juveniles were able to take bananas by day 48 and dog food by day 56. During their first month their mean milk consumption was 15.22% of their body weight per day and they increased in weight by 11.52g daily. During the second month their milk consumption fell to 8.48% of body weight and they gained 18.54g per day. In the final fortnight prior to weaning consumption was 4.05% of body weight and they gained 13.56g per day. (Olocco-Diz & Duggan 2004).

REP: In the Bolivian Chaco they appear to reproduce from November to May with the majority of lactating females being found in December and April (Cuéllar & Noss 2003). Breeding occurs in September in Provincia Santa Fé, Argentina. If conditions allow a second litter may be attempted in a single season. Prior to mating males follow females sniffing the genital area before mounting (Ratajszczak & Trzesowska 1997). Captive males were seen to attempt mountings throughout the year with the birthing season from February to December (Redford & Eisenberg 1992). Pregnant females are easily recognised due to a visible flattening of the carapace so that the sides barely cover the flanks, the "armour" returning to its natural position after birth (Ratajszczak & Trzesowska 1997). Litters usually consist of 2 or more rarely 3 offspring born after a gestation of 60 to 75 days. At Pozán Zoo, Poland all births took place at night with females perparing a shallow depression in the substrate using the forelegs and nose. Births were rapid with two offspring typically being born within a 10 minute period and following birth the female immediately proceeding to add more material to the "nest" so that the juveniles were concealed, eventaully entering and accompanying the offspring as soon as building is complete (Ratajszczak & Trzesowska 1997). Twins often consist of one male and one female (Nowak 1991). New-borns have soft leathery skin which gradually hardens with age, the pinnae are not yet formed and the mouth is closed except for the terminal portion. The nails are soft but they are able to crawl in search of milk. (Olocco-Diz & Duggan 2004). Lactation lasts 50-60 days with females often feeding young whilst lying on the back, and the eyes open after 16-30 days. Juveniles begin to move outside the nest at 30 days and take solid food from 35 days onwards Ratajszczak & Trzesowska (1997). Sexual maturity is reached at 9 months. (Redford & Eisenberg 1992). Ratajszczak & Trzesowska (1997) noted that interbirth intervals of captive individuals were often short, as little as 72 to 74 days in some females, and that such short periods followed successful rearings not unsuccessful breeding attempts. There was no need to remove males from the enclosure during breeding, but females were sensitive to nest disturbance by humans which frequently resulted in nest failure. During failed breedings the young were consumed by the mother leaving no trace of their existence.

BEH: General Behaviour Active by day and by night. Neris et al (2002) states that the species is more diurnal in winter and nocturnal in summer. Individuals of this species were observed to be active by day from at least July to early October in the area around PN Tte Enciso, Departamento Boquerón during 2006 and 2007 (P. Smith pers. obs.). Cuéllar & Noss (2003) describe the species as diurnal in the Bolivian Chaco and note that it is active during the hottest hours of the day with peaks of activity from 10am to 4pm. Armadillos at Pozán Zoo, Poland became quickly tame and enjoyed petting and scratching (Ratajszczak & Trzesowska 1997). Sociability Usually seen alone or in pairs in the wild (P.Smith pers.obs.). Ratajszczak & Trzesowska (1997) noted that as many as eight individuals were kept together at Pozán Zoo, Poland without any aggression being shown even when two females simultaneously raised young in the same enclosure. Refuges Burrow architecture in the Argentinean Pampas was described in detail by Abba et al (2005). They found burrows typically to consist of a steeply declining entrance tunnel that levels out to a horizontal gallery. The single entrance was approximately circular (19-20cm wide x 15-20cm high) and faced away from the prevailing wind direction. In soft terrain they descend to a mean depth of 30cm, but may be as deep as 1m if an obstacle is in the way. Fifty-seven percent of the burrows examined were found to be branched. Two burrow types were identified: longer, deeper burrows (complex) were built in harder soil and shorter, shallower burrows (simple) in soft soil. Simple burrows had a mean length of 70cm and mean depth of 50cm and were found only in soil with a high organic content. These were likely associated with feeding (60% of those examined ended in a tunnel excavated by Scarabaeid larvae (Coleoptera)) or temporary refuges from potential predators. These burrows are frequently clustered to some degree. Complex burrows were located in hard, calcareous soil with little moisture and reached 485cm in length and 100cm in depth. Seven of the 34 complex burrows found had chambers near the mouth or at the end, and mean chamber dimensions were 20 x 30 x 50cm. These likely represent permanent, home burrows and were always located in areas that were not subject to flooding. Burrows may be shared by a mated pair but lack nesting material. Defensive Behaviour When pursued this species runs rapidly towards its burrow, frequently adopting a zig-zagging course and heading through dense, and often thorny vegetation in an attempt to shake its pursuer (P. Smith pers. obs.). Nowak (1991) states that they may give a snarling noise when pursued and that if overtaken they draw the legs under the body so that the carapace is in contact with the ground. Upon entering a burrow they may spread the feet and arch the body so that the claws and edges of the movable bands anchor the animal in place, making it impossible to remove them by force. If surprised at great distance from their home burrow they may immediately try to dig (Parera 2002). Vigilant individuals can rise up onto the hind legs using the tail for support (Parera 2002). Enemies In Argentina the principal predator is Puma and the species is also undoubtedly taken by Jaguar in the Paraguayan Chaco. Foxes probably take young animals. Parasites Navone (1990) recorded the following nematodes in this species in the Argentinean Pampas - Aspidodera fasciata, Aspidodera scoleciformis (Aspidoderidae), Dipetalonema anticlava (Dipetalonematidae), Trichohelix tuberculata (Molineidae), Mazzia bialata (Cosmocercidae) and Ancylostoma caninum (Ancylostomidae) and Pterygodermatites chaetophracti (Rictularidae) in the Espinal region. Longevity Captive individuals have survived for 20 years (Nowak 1991).

VOC: Females disturbed at the nest emerge and growl (Redford & Eisenberg 1992). Captured animals can produce a quiet grunting sound by contracting the abdomen (Parera 2002). Suckling young make a noise similar to a cats murmur (sic) (Ratajszczak & Trzesowska 1997).

HUM: The species is consumed by indigenous populations in the Chaco, though it is not the favoured armadillo species for the table. Campesinos tend to avoid eating the species because of its scavenging habits (Neris et al 2002). In Argentina the species is hunted in winter when fat deposits make them heavier. Due to its poor eyesight it is prone to be a victim of roadkill and may also be hunted by domestic dogs. In agricultural areas they may be considered a pest for their habit of burrowing into soft soil. (Chiarello et al 2006, Parera 2002)

CON: The Greater Hairy Armadillo is considered Low Risk, least concern by the IUCN, click here to see their latest assessment of the species. The species is not listed by CITES. The species was first confirmed to occur in Paraguay as late as 1979 (Myers and Wetzel 1979), reflecting the previous inaccessibility of its habitat rather than the rarity of the species. Due to the wide distribution, isolated nature of its chosen habitat in Paraguay and apparent abundance it appears to be under no imminent threat. The species is present in several protected areas. It is able to adapt readily to habitats altered by humans and may even benefit from the association due to its ability to scavenge on refuse. (Chiarello et al 2006).

Citable Reference: Smith P (2008) FAUNA Paraguay Online Handbook of Paraguayan Fauna Mammal Species Account 11 Chaetophractus villosus.

Last Updated: 23 June 2009.

References:

Abba AM, Sauthier DEU, Vizcaino SF 2005 - Distribution and Use of Burrows and Tunnels of Chaetophractus villosus (Mammalia: Xenarthra) in the Argentinean Pampas - Acta Theriologica 50: p115-124.

Azara F de 1801 - Essais sur l´Histoire Naturelle des Quadrupèdes de la Province du Paraguay - Charles Pougens, Paris.

Burmeister H 1861 - Reise durch die La Plata-Staaten mit Besonderer Rücksicht auf die Physische Beschaffenheit und den Culturzustand der Argentinischen Republik Ausgeführt in den Jahren 1857, 1858, 1859 und 1860 - HW Schmidt, Halle.

Cartés JL 2007 - Patrones de Uso de los Mamíferos del Paraguay: Importancia Sociocultural y Económica p167-186 in Biodiversidad del Paraguay: Una Aproximación a sus Realidades - Fundación Moises Bertoni, Asunción.

Ceresoli N, Jimenez GT, Duque EF 2003 - Datos Morfómetricos de los Armadillos del Complejo Ecológico de Sánz Peña, Provincia del Chaco, Argentina - Edentata 5: p35-37.

Chiarello A, Cuéllar E, Meritt D, Porini G, Members of the Edentate Specialist Group 2006 - Chaetophractus villosus in IUCN 2008. 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species Downloaded 4 January 2008.

Cuéllar E, Noss A 2003 - Mamíferos del Chaco y de la Chiquitania de Santa Cruz, Bolivia - Editorial FAN, Santa Cruz.

de la Peña MR, Pensiero JF 2004 - Plantas Argentinas: Catálogo de Nombres Comúnes - LOLA, Buenos Aires.

Desmarest AG 1804 - Tableau Méthodique des Mammifères in Nouveau Dictionnaire d´Histoire Naturelle, Appliquée aux Arts, Principalement à l`Agriculture, à l`Économie Rurale et Domestique: Par une Société de Naturalistes et d`Agriculteurs: Avec des Figures Tirées des Trois Règnes de la Nature - Deterville Vol 24, Paris.

Edentate Specialist Group 2004 - The 2004 Edentate Species Assessment Workshop - Edentata 6: p1-26.

Eisenberg JF, Redford KH 1999 - Mammals of the Neotropics: Volume 3 The Central Neotropics - University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Fischer G 1814 - Zoognosia Tabulis Synopticis Illustrata: Volumen Tertium. Quadrupedum Reliquorum, Cetorum et Monotrymatum Descriptionen Continens - Nicolai Sergeidis Vsevolozsky, Mosquae.

Fitzinger LJ 1871 - Die Natürliche Familie der Gürtheliere (Dasypodes) I Abtheilung - Sitzungsber. Kaiserl. Akad. Wiss. Wien 64:p209-276.

Gardner AL 2007 - Mammals of South America Volume 1: Marsupials, Xenarthrans, Shrews and Bats - University of Chicago Press.

Gray JE 1865 - Revision of the Genera and Species of Entomophagous Edentata, Founded on the Examination of the Specimens in the British Museum - Proceedings of Zoological Society of London 1865: p359-386.

Greegor D H 1975 - Renal capabilities of an Argentine desert armadillo - Journal of Mammalogy 56: p626-632.

Larrañaga DA 1923 - Escritos - Instituto Histórico y Geográfico del Uruguay, Montevideo.

Lesson RP 1827 - Manuel de Mammalogie ou Histoire Naturelle des Mammifères - Roret, Paris.

Linnaeus C 1758 - Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species cum Characteribus, Diferentiis, Synonymis, Locis. Editio Decima. - Laurentii Salvii, Holmiae.

Molina GI 1782 - Saggio sulla Storia Naturale del Chili - Stamperia di S.Tommaso d´Aquino, Bologna.

Möller-Krull M, Delsuc F, Churakov G, Marker C, Superina M, Brosius J, Douzery EJP, Schmitz J 2007 - Retroposed Elements and Their Flanking Regions Resolve the Evolutionary History of Xenarthran Mammals (Armadillos, Anteaters and Sloths) - Molecular Biology and Evolution 24: p2573-2582.

Myers P, Espinosa R, Parr CS, Jones T, Hammond GS, Dewey A 2006 - The Animal Diversity Web (online). Accessed January 2008.

Myers P, Wetzel RM 1979 - New Records of Mammals from Paraguay - Journal of Mammalogy 60: p638-641.

Navone GT 1990 - Estudio de la Distribución, Porcentaje y Microecología de los Parásitos de Algunas Especies de Edentados Argentinos - Studies in Neotropical Fauna and Environment 25: p199-210.

Neris N, Colman F, Ovelar E, Sukigara N, Ishii N 2002 - Guía de Mamíferos Medianos y Grandes del Paraguay: Distribución, Tendencia Poblacional y Utilización - SEAM, Asunción.

Nowak RM 1991 - Walker´s Mammals of the World 5th Ed Volume 1 - Johns Hopkins, Baltimore.

Olfers I 1818 - Bemerkungen zu Illiger´s Ueberblick der Säugthiere, nach Ihrer Vertheilung über die Welttheile, Rücksichtlich der Südamerikanischen Arten p192-237 in Bertuch FI Neue Bibliothek der Wichtigsten Reisebeschreibungen zue Erweiterung der Erd - und Völkerkunde; in Verbindung mit Einigen Anderen Gelehrten Gesammelt und Herausgegeben - Verlage des Landes-Industrie-Comptoirs, Weimar.

Olocco-Diz MJ, Duggan A 2004 - The First Hand-rearing of Larger Hairy Armadillos Chaetophractus villosus at the Temaikén Foundation - Edentata 6: p27-30.

Olocco-Diz MJ, Quse B, Gachen GG 2006 - Registro de Medidas y Pesos del Tubo Digestivo de un Ejemplar de Chaetophractus villosus - Edentata 7: p23-25.

Parera A 2002 - Los Mamíferos de la Argentina y la Región Austral de Sudamérica - Editorial El Ateneo, Buenos Aires.

Rapp W 1852 - Anatomische Untersuchungen über die Edentaten. Zweite Verbesserte und Vermehrte Auflage - Ludwig Friedrich Fues, Tübingen.

Ratajszczak R, Trzesowska E 1997 - Management and Breeding of the Larger Hairy Armadillo, Chaetophractus villosus, at Pozan Zoo - Der Zoologische Garten 67:p 220-228.

Redford KH, Eisenberg JF 1992 - Mammals of the Neotropics: Volume 2 The Southern Cone - University of Chigaco Press, Chicago.

Schreber JCD von 1774 - Die Säugthiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur mit Beschreibungen - Wolfgang Walther, Erlangen.

Trouessart EL 1898 - Catalogus Mammalium tam Viventium quam Fossilium. Fasciculus V: Sirenia, Cetacea, Edentata, Marsupialia, Allotheria, Monotremata - R.Friedländer & Sohn, Berolini.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many thanks to Mariella Superina for assisting with obtaining some of the references used in the construction of this species account.

MAP 11:

Chaetophractus villosus

Designed by Paul Smith 2006. This website is copyrighted by law.

Material contained herewith may not be used without the prior written permission of FAUNA Paraguay.

Photographs on this web-site are used with permission.